Rook, in his role of unacknowledged puppet-master, had made the phone calls to the press on his own initiative. Even though he was not fool enough to join the demonstrators, he watched them from his usual cafe table and was pleased. Two hundred out of two-o-eight was good, though not all the men and women there were stallholders. Some were porters, some were soapie wives and sons. Others represented the cafes and the bars that Victor wished to level to the ground. There were some customers, too — a dozen men and women from restaurants and small hotels in the Woodgate district who bought fresh produce from the Soap Market and liked the cheaper prices. They all feared change. Yet they believed that change could be confronted and repelled. Remember how the residents of Stephens Well, a small and wealthy suburb, had beaten back developers, or beaten them down at least. They’d forced the architects to lop three storeys from the top of their new office block because it cast a shadow on the suburb’s private park for forty minutes every day. That contravened the ancient Law of Light. Consider how the city’s conservation groups had stopped the widening of roads when widening would bring down trees. Trees of that age and size were protected by the Sylvan Ordinances of 1910. The marketplace had trees and light as well. So there was hope.

Rook drank his coffee, and peered at everyone who passed. His newspaper was spread out across his lap, unread and wet. It did not matter what the headlines were, or what the world was coming to, or that, if NASA got it right, an asteroid, one kilometre in width and travelling at 74,000 kilometres per hour, would ‘wing’ the Earth at noon, missing the Soap Market (also one kilometre in width) by an astronomically narrow half a million kilometres of space. His mind was focused on the detail of his life and not Eternity. Here — within a stone’s throw — he and the soapies were confronted by a danger they could witness, understand and quantify in human measurements. Here was a space they could protect.

Of course the market did not close. The marchers all had partners, deputies, or family to defend them from a trading loss. Each stall was open and the crowds were much the same as on any other day, at least on any other day that rained as hard as this. The demonstrators used their placards as screens against the rain. They pulled on hats. The television unit clothed its camera in a plastic hood. Someone had thought to bring a drum and he was ordered to the front by Con. They set off through the marketplace a trifle sheepishly, routed and regrouped by Cellophane. He’d never known such ordered crowds, such unity, before.

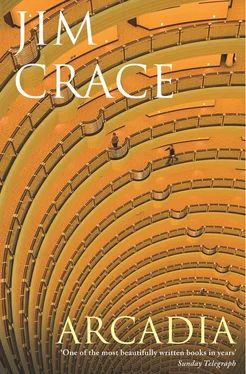

It’s difficult to concentrate on grievances when all around are friends. Con had a dozen leafleters. The Soap Fund — a reserve to pay for traders’ funerals or help out widows or support those injured at their work — had provided money for paper and printing. The leaflet showed the Busi sketch in ink and wash of Arcadia. Its black and Gothic banner was ‘Arcadia? Who pays?’ — and then it listed, with more regard for impact than for grammar, ‘ You , the shopper … Me , the trader … Us , the citizens … Them that value history and tradition.’

When they had regrouped, at the Mathematical Park, to enter Tower Square and curve round with the traffic into Saints Row, the leafleters set to work, walking in the road to press their message on to drivers, dodging through the pavement crowds. The crowds, in fact, had slowed to let the traders through. They had no choice. Their umbrellas made it difficult to negotiate a passage through the squints and alleys of a throng. It only takes a drum to cause the gawpers in the street to stand and watch, or to make those drivers with a little time to spare twist at their steering wheels to see what the drum might signify. Once a few had stopped to look, then everybody slowed. The usual speeding lava of the streets had cooled. Then there were horns and tempers. Pedestrians, blocked on the pavements by the ones who stopped to watch, spilled out onto the street and tried to hurry on between the cars and vans and gusts of rain. A courier motorcyclist bumped up on the pavement, and tried to clear a passage for himself.

The soapies could not find an easy way. Only the drummer, whose pulse and drumsticks seemed to threaten anyone that blocked his path, proceeded with much speed. The camera crew and the photographers walked backwards through the traffic. Their lenses squared the scene and transformed this hapless chaos, unintended and shortlived, into an act of scheming anarchy. Marching in a traffic jam to the formal beat of drum and to the blatant discord of car horns, the protest had undermined itself. It could hardly move. The rule of modern cities is that wheels and legs must keep on moving or keep out of town. At least they should keep separate. They should observe the segregations of the kerb.

The police arrived — a single officer, already wet and robbed of patience — and there were comic scenes adorning both the evening and the morning television news and the front pages of the daily papers, showing the drummer and policeman eye to eye. Both had their sticks raised in the air, both were intent on beating skin. The policeman, though, had been discreet and brought his nightstick down upon the drum and not the drummer. The drummer was less restrained. He beat a tattoo on the policeman’s hat. In the photograph, two traders were stepping forward through the jam of cars to intervene. They held placards as if they meant to chop the policeman down. One placard said, They Shall Not Pass — ironically, in view of all the chaos in the street. The other exhorted, Save our Market from the Millionaire. That was the picture that the city saw. Those were the slogans that introduced them to Arcadia.

The traders were elated. Now they understood that, for a while at least, two hundred citizens could bring the city to a halt. They formed a crowd, a laughing, animated crowd, at the top of the steps to the tunnel beneath Link Highway Red. Soon they were chanting slogans with one voice, walking unencumbered except by wind and rain down the centre of the mall. Their voices ricocheted wetly off the office glass and stone and sounded like a bullet sounds when it is shot in a ravine and lodges in the buttocks of an elk. They were loud enough to summon Signor Busi and his host from their breakfast to the parapet of Victor’s rooftop garden, and to crowd the tinted, toughened windows of Big Vic with staff, including Anna on the 27th floor.

The mall had not witnessed noise or passion such as this, not since the builders had removed their huts and debris and left the buildings clean and free for business. The architecture said Don’t raise your voice, Don’t run, Don’t hang around . Office workers, coming, going, did what they were told. The mall prepared them for the obeisances of the office desk just as the aisles of churches subdue their congregations between the door and the altar. But the procession of greengrocers was not intimidated by the prospect of a desk. Encouraged by the cameras, the echo and the camaraderie of rain, they bellowed slogans down the mall. The closer that the soapies got to Big Vic, the unrulier they became. To see their faces you would think that they were mutinous and angry. In fact, these men and women were having fun. What is more fun than making noisy mayhem in a place where you’re not known but, yet, are flanked by a company of friends? For once they felt like crusaders instead of selfish middlemen in trade. This day enriched them. Indignation and a drum would save their market from Arcadia.

They lined up with their placards outside Big Vic, unprotected from the rain, ennobled by discomfort, emboldened by their fears of being driven from their stalls. What then? No one had thought to make a speech or send a deputation in or lobby for support and signatures from Victor’s office staff.

Читать дальше