Today, they are all three lying down.

Now, in the heart of winter, they spend a lot of time lying around in the snow.

Does she lie down because the other two have lain down before her, or are they all three lying down because they all feel it is the right time to lie down? (It is just after noon, on a chilly, early spring day, with intermittent sun and no snow on the ground.)

Is the shape of her lying down, when seen from the side, most of all like a boot-jack as seen from above?

It is hard to believe a life could be so simple, but it is just this simple. It is the life of a ruminant, a protected domestic ruminant. If she were to give birth to a calf, though, her life would be more complicated.

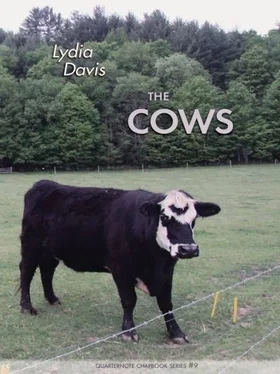

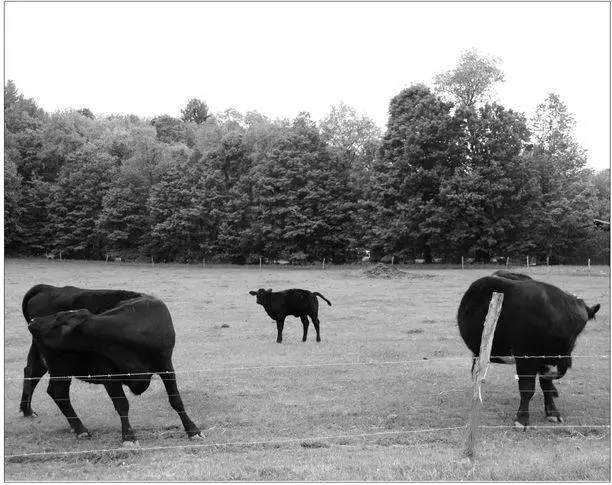

The cows in the past, the present, and the future: They were so black against the pale yellow-green grass of late November. Then they were so black against the white snow of winter. Now they are so black against the tawny grass of early spring. Soon, they will be so black against the dark green grass of summer.

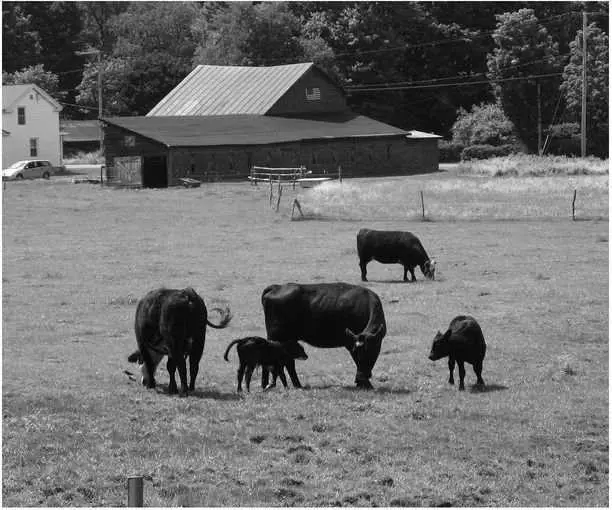

Two of them are probably pregnant, and have probably been pregnant for many months. But it is hard to be sure, because they are so massive. We won’t know until the calf is born. And after the calf is born, even though it will be quite large, the cow will seem to be just as massive as she was before.

The angles of a cow as she grazes, seen from the side: from her bony hips to her shoulders, there is a very gradual, barely perceptible slope down, then, from her shoulders to the tip of her nose, down in the grass, a very steep slope.

The position, or form, itself, of the grazing cow, when seen from the side, is graceful.

Why do they so often graze side-view on to me, rather than front- or rear-view on? Is it so that they can keep an eye on both the woods, on one side, and the road, on the other? Or does the traffic on the road, sparse though it is, right to left, and left to right, influence them so that they graze parallel to it?

Or perhaps it isn’t true that they graze more often sideways on to me. Maybe I simply pay more attention to them when they are sideways on. After all, when they are perfectly sideways on, to me, the greatest surface area of their bodies is visible to me; as soon as the angle changes, I see less of them, until, when they are perfectly end-on or front-on to me, the least of them is visible.

They make slow progress here and there in the field, with only their tails moving briskly from side to side. In contrast, little flocks of birds — as black as they are — fly up and land constantly in waves behind and around them. The birds move with what looks to us like joy or exhilaration but is probably simply keenness in pursuit of their prey-the flies that in turn dart out from the cows and settle on them again.

Their tails do not exactly whip or flap, and they do not swish, since there is no swishing sound. There is a swooping or looping motion to them, with a little fillip at the end, from the tasseled part.

Her head is down, and she is grazing within a circle of darkness that is her own shadow.

Just as it is hard for us, in our garden, to stop weeding, because there is always another weed there in front of us, it may be hard for her to stop grazing, because there are always a few more shoots of fresh grass just ahead of her.

If the grass is short, she may grasp it directly between her teeth and her lip; if the grass is longer, she may capture it first with a sideways sweep of her tongue, in order to bring it into her mouth.

Their large tongues are not pink. The tongues of two of them are light gray. The tongue of the third, the darkest one, is dark gray.

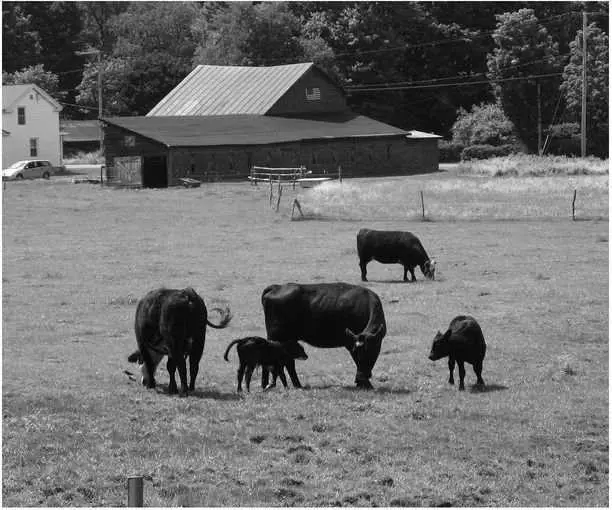

One of them has given birth to a calf. But in fact her life is not much more complicated than it was before. She stands still to let him nurse. She licks him.

Only the hours of the birth itself, on that day (Palm Sunday), were much more complicated.

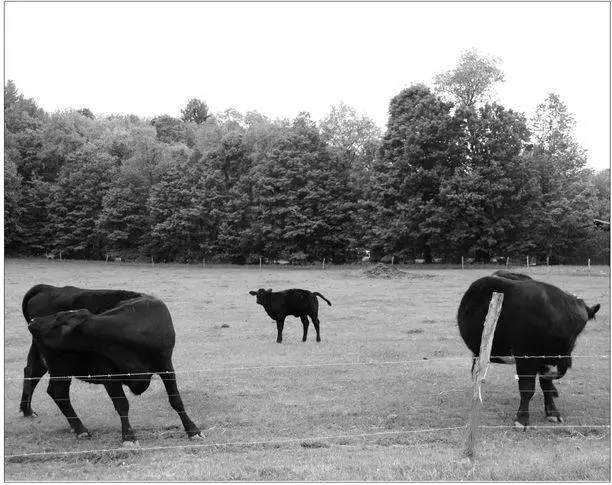

Today, again, the cows are positioned symmetrically in the field, but now there is a short stray line of dark in the grass among them — the calf sleeping.

There used to be three dark horizontal lumps on the field when they lay down to rest. Now there are three and another very small one.

Soon he, three days old, is grazing, too, or learning to graze, but so small, from where I stand watching him, that he is sometimes hidden by a twig.

When he stands still, a miniature, nose to the grass like his mother, because his body is still so small and his legs so thin, he looks like a thick black staple.

When he runs after her, he canters like a rocking horse.

They do sometimes protest — when they have no water, or can’t get into the barn. One of them, usually the darkest, will moo in a perfectly regular blast twenty or more times in succession. The sound echoes off the hills like a fire alarm coming from a fire house.

At these times, she sounds authoritative. But she has no authority.

A second calf is born, to a second cow. Now, one small dark lump in the grass is the older calf. Another, smaller dark lump in the grass is the newborn calf.

The third cow could not be bred because she would not get into the van to be taken to the bull. Then, after a few months, they wanted to take her to be slaughtered. But she would not get into the van to be taken to slaughter. So she is still there.

Other neighbors may be away, from time to time, but the cows are always there, in the field. Or, if they are not in the field, they are in the barn.

I know that if they are in the field, and if I go up to the fence on this side, they will, all three, sooner or later come up to the fence on the other side, to meet me.

They do not know the words “person,” “neighbor,” “watch,” or even “cow.”

At dusk, when our light is on indoors, they can’t be seen, though they are there in the field across the road. If we turn off the light, and look out into the dusk, gradually they can be seen again.

They are still out there, grazing, at dusk. But as the dusk turns to dark, while the sky above the woods is still a purplish blue, it is harder and harder to see their black bodies against the darkening field. Then they can’t be seen at all, but they are still out there, grazing in the dark.

Читать дальше