Some of the young men from the new generation in the neighborhood now call me the madman of Freedom Square. The government planted some trees and put some benches where the statues of the blonds had stood. They put up a large plaque with the new name of the neighborhood: Freedom district. I know what these idiots say. They claim that the piece of shrapnel that went into my head damaged my brain. But they are just villagers still living in the Dark Age. I have repeatedly asked the notables and others to contribute money to rebuild the statues of the blonds and protect the history of the neighborhood. This is the least I could do to repay them the favor of saving my life. What makes me angry is that even my father no longer believes in the story of the blonds, after the soldiers demolished the statues and killed many young men that night. Some people now claim that the story of how the blonds miraculously appeared that night and fought on our side is just cheap propaganda, spread by certain youngsters to raise the morale of our fighters, and that the government army wiped out the resistance before morning broke. But I am quite sure it was the blonds who carried me on the white stretcher, and with these very fingers of mine I touched their angelic hair.

A few days ago I met a stranger whom I believe to be honest, not a fake like most of the people in the neighborhood, and he told me he believed my story of how the blonds appeared that night. He spoke to me at length about how we have lost our history and heritage because of the agents of the West and because we have neglected our religion, and how freedom means not becoming stooges in the hands of the infidels, but what I don’t fully understand is the wide belt the man wrapped around my waist in his house this morning. I feel very hot because the belt is so heavy. I’ll sit down in the shade of the tree…. Damn, the women and children have taken all the benches.

WE WERE MEANT TO CAMP IN AN OLD GIRL’S SCHOOL, and some of the soldiers decided the best place to spend the night was the school’s air-raid shelter. Daniel the Christian picked up his blanket and other bedding and headed out into the open courtyard.

“Of course, Chewgum Christ is crazy,” remarked one of the soldiers, a man as tall as a palm tree, his mouth stuffed with dry bread.

“Perhaps he doesn’t want to sleep with us Muslims,” suggested another soldier.

The young men were monkeys. They didn’t know the truth about Daniel. They were too busy masturbating on the benches in the classrooms where the girls used to sit. Just one missile and they would shortly be charred pricks. In absurd wars such as this one, Daniel’s gift was a lifesaver. We had been together in the Kuwait war, and if it hadn’t been for his amazing powers we wouldn’t have survived. Aside from his gloomy nature, Daniel could hardly be considered ordinary flesh and blood. He was a force of nature.

I spread out my blanket close to him and lay on my back, like him, staring into space.

“Go to sleep, Ali, my friend. Go to sleep. There’s no sign tonight. Go to sleep,” he said to me, and started snoring straightaway.

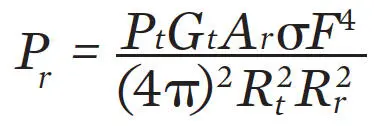

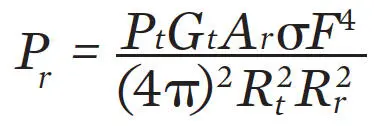

Daniel was always chewing gum. The soldiers had baptized him Chewgum Christ. I often imagined that Daniel’s chewing was like an energy source, recharging the battery that powered the screen in his brain. His life’s dream was to work in the radar unit. He had completed high school and volunteered to join the air force, but his application was rejected, maybe because his father had been a prominent communist in the seventies. He loved radar the way other men love women or soccer. He collected pictures of radar systems and talked about signals and frequencies as though he was talking about a romp in the hay with some girlfriend. During the last war, I remember him saying, “Ali, humans are the best radar receivers, compared with other animals. You just need to practice making your spirit leave your body and then bring it back, like exhaling and inhaling.” He had tattooed on his right arm the radar equation:

After Daniel’s hopes of joining the air force were dashed, he volunteered for the medical corps. But he did not give up his passion for radar, and anyone who knew him would not have been surprised by this obsession, because Chewgum Christ was himself the strangest radar in the world. I remember those terrifying nights during the war over Kuwait. The soldiers, as frightened as ducklings, would follow him wherever he went. The coalition planes would be bombing our trenches, and we wouldn’t be able to fire a single shot back. We felt like we were fighting some ultimate, almighty force. All we could do was dig more trenches and scamper from place to place like rats. In the end we camped near the desert. All we had left was our faith in God and the powers of Daniel the Christian. One night we were eating in the trench with the other soldiers when Daniel started complaining of a stomachache. The soldiers stopped eating, picked up their weapons, and prepared to stand, all of them looking at Daniel’s mouth.

“I want to lie down in the shade of the large water tank,” Christ said finally.

The soldiers joined him as he left the trench, jostling to keep close to him as if he were a shield against missiles. They sat around him in the shade. Just thirty-five minutes later three bombs fell on the trench. It wasn’t the only time. Christ’s premonitions saved many soldiers. In Daniel’s company the war played out like the plot of a cartoon. In the blink of an eye, reality lost cohesion. It fell apart and you started to hallucinate. What could one make, for example, of the way a constant itching in Daniel’s crotch foretold that an American helicopter would crash on the headquarters building? Is it credible that three successive sneezes from Daniel could foretell a devastating rocket attack? They fired them at us from the sea. We soldiers were like sheep, fighting comic book wars.

I heard many rumors that reports on Christ had been submitted to the Supreme Command. But the chaos of those days and the defeat of our army, which was crushed like flies, prevented the authorities from paying any attention. There were many stories about the President’s interest in magicians, the occult, and people with prodigious powers. They claim it was at his suggestion that so many books on parapsychology were unexpectedly translated in Iraq in the eighties, because he had heard that the advanced countries were developing telepathic techniques and using them for espionage. The President thought that science and the occult were one and the same; they just used different methods to reveal the same secrets.

Christ was not boastful about his premonitory powers and did not consider them unusual. He used to tell stories from history about mankind’s ability to foretell the future. I came to the conclusion that Daniel’s melancholia made it impossible for him to take pleasure in the talent he possessed. Even his interest in radar did not bring him pleasure. His ideas about happiness were mysterious. I understood from him that he was frightened by some inner gloom. He thought his talent was just another sign of how impotent and insignificant we are in this mysterious world. He told me that at an early age he read a story by an Iraqi writer whose personality was simultaneously sarcastic and fearful. The hero in the story was swallowed by a shark after a fierce battle in the imaginary river of time. The hero sits trapped in the darkness there and thinks alone, “How can I reconcile my private life with my awareness that a world is collapsing in front of my eyes?”* “That’s a question that has weighed on my life. It has kept me awake like an open wound,” said Christ.

Читать дальше