* * *

“When Gāyatrī flew toward Soma, a footless archer, aiming at her, shot off a feather, either of Gāyatrī or of King Soma; and the feather, dropping down, became a parṇa tree.” Elsewhere we are told that this mysterious footless archer is called Kṛśānu, but we learn little more. His appearance and attitude suggest a being on the margin of the unmanifest — or of “fullness,” pūṛna , which is another name for it. Like another archer — Rudra — Kṛśānu tries to stop a deed that goes against the order of the world, and thereby creates life as we know it. In the case of Rudra, it was Prajāpati’s incest with Uṣas. In his case, it is the abduction of the soma , which will enable men to become drunk on it. Kṛśānu’s nature is perhaps also implied in his being “footless,” apād , a characteristic that links him with another enigmatic figure: Aja Ekapād, the one-footed goat. If we go back to the “unborn,” aja , to the “self-existing,” svayambhū , the last two figures that let themselves be recognized — though only in flashes and glimmers, without ever being described — are a Goat (Aja Ekapād) and a Serpent (Ahi Budhnya). We can distinguish nothing beyond them. The Goat has to stand up because it is the “supporter of the sky,” but if we look closer we see it is resting on only one hoof ( ékapād ). At times it appears as a column of fire speckled with black, the black of the darkness against which it stands out. And beneath it? The Serpent of the Deep, Ahi Budhnya. No text dares to say any more about it. Only its name is mentioned — five times, in the Vedic hymns, along with that of the Goat, as if these two figures hint at something beyond which we cannot go: the Unborn, the Deep. The inevitable and almost imperceptible channel for all that exists.

The world owes its existence to the infinitesimal delay of an arrow. Or of two arrows: that of Rudra, which pierced Prajāpati’s groin, but did not prevent him from spilling his seed, and that of Kṛśānu, which grazed the wing of the hawk carrying the soma and made one of its feathers drop to the ground, but did not stop the soma from reaching mankind. That particle of time was all time, with its uncontainable power. It was the way out of plenitude closed up within itself, the passage to plenitude brimming over into something else, into the world itself. But that superabundance had happened thanks only to a wound. The rites Vedic people sought to establish were primarily an attempt to treat and heal that wound, thereby renewing it. And burning one part of the superabundance that enabled them to live.

* * *

Soma not only induced intoxication, but encouraged truth. “For the man who knows, this is easy to recognize: true and false words clash. Of these two, the true, the just, is what Soma protects. And he fights untruth”: This is hymn 7.104 of the Ṛgveda. This double gift — rapture and the true word — is what distinguishes Vedic knowledge. If Soma did not lead to rapture, it could not fight for the true word either. And much the same happens to anyone who receives Soma into the circulation of their mind. Dionysus was swept into rapture and used sarcasm against anyone who opposed him. He never claimed to protect the true word. It was as if the word passed among his retinue of Maenads and Satyrs, but without being much noticed. Dionysus was intensity in its purest state, that overcame and destroyed every obstacle, without dwelling on the word, whether true or false. Possessed by the god, the bacchant declared: “Make way, make way / let lips not be contaminated with words.”

* * *

“Now we have drunk soma ; we have become immortal; we have attained the light, we have found the gods.” Sudden, lightning words, the opposite of the sequence of riddles that makes up so much of the Ṛgveda. Men need soma so that they can find the gods; but the gods, in turn (and primarily their king, Indra) need soma in order to be gods. They chose soma one day as their intoxicating drink because “the vigor of the gods” is due to soma.

If soma is desired just as much by the gods as by men, it will also become their factor in common. Only in rapture can gods and men communicate. Only in soma do they meet: “Come toward our pressings, drink soma , you soma drinker.” This is how people address Indra, in the first hymn dedicated to the god in the Ṛgveda. Only insofar as people are able to offer rapture to the gods can they hope to attract them to the earth. What people offer the god is what the god himself has conquered for them — and for the other gods — committing the gravest of crimes, the killing of a brahmin, when he cut off the three heads of Viśvarūpa. There is a secret understanding between Indra and men, for Indra is the god who most resembles men (and several times he will be mocked for this): he has killed a brahmin to obtain the soma , in the same way that people kill King Soma to obtain the intoxicating liquid from which he is made. Killing, sacrifice, and rapture are bound together, both for god and man. And this makes them accomplices, it obliges people to celebrate long, exhausting soma rites. But it is also the only way of attaining a life that — for a while — is divine.

ANTECEDENTS AND CONSEQUENTS

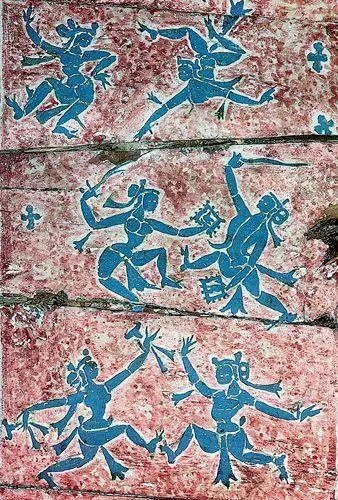

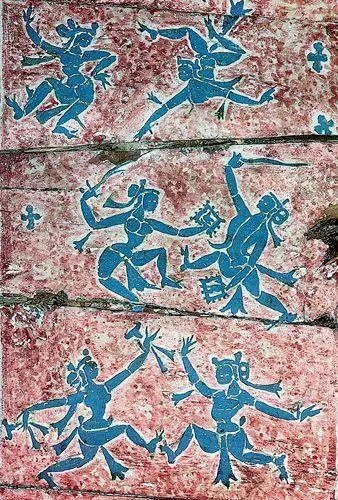

When you gods were in the waves, holding each other tightly, thick foams then rose up from you, as from dancers.

—Ṛgveda 10.72.6

This book was started quite a number of years ago out of the rash idea of writing a commentary on the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa , the Brāhmaṇa of One Hundred Paths. The Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa is a treatise on Vedic rituals that dates back to the eighth century B.C.E. and is made up of fourteen kāṇḍas , “sections,” which add up to 2,366 pages in Julius Eggeling’s five-volume translation in the Sacred Books of the East series, published in Oxford between 1882 and 1900. This is at present the only complete translation (that of C. R. Swaminathan has so far reached only the eighth kāṇḍa ). The Brāhmaṇas — and the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa stands out among them — contain thoughts that cannot be ignored yet rarely find a place in the philosophy books. Thus, very often, they were treated with impatience, as being a sort of intrusion.

The Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa is a powerful antidote to current existence. It is a commentary that shows how one can live a life totally dedicated to passing into another order of things, which the text dares to call “truth.” A life that is impossible to live, since almost everything is worn down in the strains of that transition. But a life that certain people tried, very long ago — and of which they wanted to leave some record. It was a life based above all on particular gestures. We should not be led astray by the fact that some of those gestures still survive today in India and are commonly performed by a great many people who know almost nothing about how they originated, while other great civilizations have left no comparable legacy: the civilization of the Vedic ritualists did not withstand the test of time — it fell apart, remaining for the most part inaccessible, incomprehensible. And yet all that still shines out of it has a power that stirs any mind not entirely enslaved to what surrounds it.

* * *

People at the beginning of the twenty-first century speak much about religion. But very little in the world is religious in the strict and rigorous sense. And not so much with regard to individuals as to social structures. Whether these are churches, sects, tribes, or ethnic groups, their model is an amorphous superparty that lets people go further than the idea of the party had previously allowed, in the name of something that is often described as “identity.” It is the revenge of secularity. Having lived for hundreds and thousands of years in a condition of subjection, like a handmaiden to powers that were imposed without caring to justify themselves, secularity now — sneeringly — offers all that still makes reference to the sacred the means to act in a way that is more effective, more up-to-date, more deadly, more in keeping with the times. This is the new horror that still had to take form: the whole of the twentieth century has been its long incubation period.

Читать дальше