How was this astonishing reversal reached, through which Death became liberation from death? It was a process with various stages. In the beginning, “Prajāpati created living creatures: from upward breaths he produced the gods, from downward breaths mortals. And, over living creatures, he created Death as the one who devours them.” Farther on, the same kāṇḍa of the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa speaks of Prajāpati who, “having created living things, felt emptied and was frightened of Death.” Later, it says: “Death, which is evil ( pāpmā mṛtyuḥ )” overcame Prajāpati while he was creating. The farther we venture in the text, the closer Mṛtyu comes to Prajāpati and surrounds him: an impending presence, finally a dueling presence. When we reach the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad , the situation is reversed: there is no more mention of Prajāpati, it is now Mṛtyu — and it is Death who now submits to all the tests, to all the labors faced by Prajāpati. Does this mean the Upaniṣad radically changes viewpoint? Definitely not. Everything had already been established. Back in the tenth kāṇḍa of the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa we read that Prajāpati is “the Year, Death, the Ender.”

* * *

At the age of eight, the young brahmin came before the master and said: “I am here to become a pupil.” The master then asked him: “ Ka (Who, What) is your name?” The question included the answer: “ Ka is your name.” At that moment the pupil came under the shadow of Prajāpati, taking even his name: “Thus he makes him one belonging to Prajāpati and initiates him.” Everything else was a consequence. The master took his pupil’s right hand and said: “You are a disciple of Indra. Agni is your master.” Powerful divinities, who cast a shadow. And in that shadow were Prajāpati and the pupil himself, who was about to undergo a long transformation. It would last twelve years.

* * *

“Prajāpati is truly that sacrifice which is performed here; and from which these creatures are born: and likewise they are born again today.” These clear-cut words are found three times within a few pages. They sound like a warning, an opening chord. They remind us that Prajāpati’s theology is above all a liturgy. It is not just a matter of reconstructing Prajāpati’s original actions in which living beings were created. It is now a matter of carrying out corresponding actions so that living beings continue to be produced. Prajāpati’s action is uninterrupted and perpetual. It is the action that is carried out in the mind, in every mind, whether it knows it or not, when forms break away from its inarticulate and borderless dominion — forms that have an outline and stand out among everything else.

* * *

For the Vedic seers, cosmogony was not the traditional tale of primordial times, but a literary genre that allowed for an indefinite number of variants. And all were compatible— iva , “so to speak.” Or at least, all converged on one ever-present point — the sacrifice. Sacrifice was the breath of the multiple cosmogonies: stories of a specific sacrifice that at the same time were the foundation of the sacrifice. There are many different versions in one and the same work about what originally happened to Prajāpati. And each new version is meant to explain some detail about the world as it is. If the stories about Prajāpati were not so richly varied, the world would be poorer, less vital, less capable of metamorphosis. The more variegated the origin, the denser and more impenetrable is the texture of everything. It is generally described as “the three worlds”: the sky, the earth, and atmospheric space. All that happens takes place between these three layers of reality. And this would be quite enough to complicate the picture, since the relationships between the three levels are extremely dense.

But the ritualist is a man of doubt. For every movement he performs, he is goaded by a question: is this the gesture to perform? Will this gesture cover the whole of reality? Or will there still be a further reality that this gesture cannot touch? Hence, at one point, the ritualist refers to a fourth world. If this world existed, it would be a disturbing revelation, since everything done up to that point had involved only three worlds. Isn’t the mere existence of the fourth enough to frustrate such a vision? And won’t perhaps the fourth world feel outraged about never having been taken into consideration? Yet “uncertain it is whether the fourth world exists.” An irresolvable doubt as to the very existence of an entire world is therefore acknowledged. What should be done? The ritualist is used to opening up a way — perhaps a temporary one — through this maze. If the existence of the fourth world is uncertain, then “uncertain is also what is done in silence.” A further movement must then be added to the movements carried out while reciting a formula, which is done in silence. That gesture will be the recognition that the fourth world might exist. That is enough to go further, on toward other gestures. But that silent doubt lingers behind all speculation. Until all of a sudden, from one side, and with a nonchalance typical of the esoteric, a sentence appears with the long-awaited answer: “Prajāpati is the fourth world, beside and beyond these three.” The answers to riddles have a peculiar feature: they become riddles themselves, and even more far-reaching. This is the case here. If Prajāpati is the “fourth world”—and the existence of the fourth world is “uncertain”—the existence of Prajāpati himself would be uncertain. If we trace back to the one who created living beings, we do not encounter something more sure and solid, but something whose existence we can indeed legitimately put in doubt, something we can nevertheless ignore without this upsetting in any way the workings of everything, of those “three worlds” with which we are constantly involved. The theological daring of the ritualists is dazzling: implicit in the mystery is its capacity to instill doubt as to its own existence, the ability to allow everything to exist without having to refer to the mystery itself. Nothing protects a mystery better than the denial of its very existence.

* * *

Prajāpati: the background noise of existence, the steady hum that goes before every sound graph, the silence behind which we perceive the workings of a mind that is the mind. It is the id of what happens, a fifth column that spies on and sustains every event.

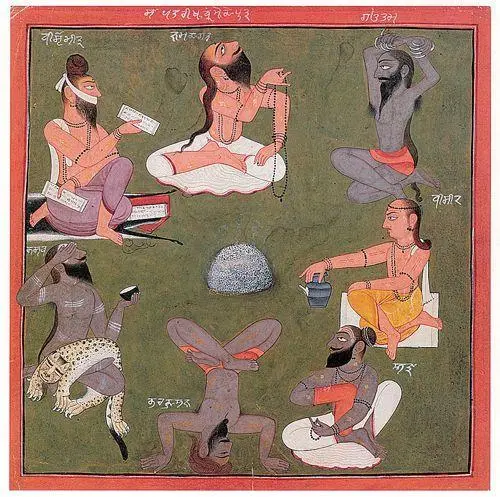

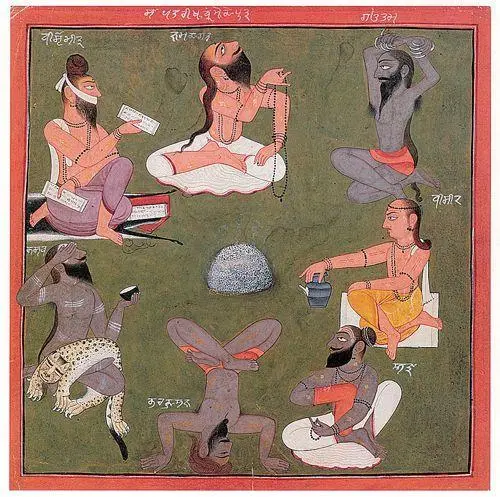

V. THEY WHO SAW THE HYMNS

The hymns of the Ṛgveda were said to have been seen by the ṛṣis. The ṛṣis may therefore be described as “seers.” They saw the hymns in the same way as we see a tree or a river. They were the most disconcerting, least easily explainable beings in the Vedic cosmos. Chief among them were the Saptarṣis, the Seven who lived in the stars of the Great Bear, who have some affinity with the Seven Greek Sages, with the Islamic abdāls , and with the Seven Akkadian Apkallus of the Apsu. But something in the very nature of the ṛṣis was an epistemological scandal: they alone were allowed to belong to the unmanifest and at the same time take part in the events of everyday life, which they secretly ruled.

And this itself was alarming: that a metaphysical category, the asat , the “unmanifest,” was a category of beings that had a name. Hermann Oldenberg felt an immediate need to clear away any inappropriate comparisons: “This non-being was of quite a different kind to Parmenides’ non-being — and there is very little here of his rigor in discussing with passionate seriousness the non-being of the non-existent.” Oldenberg’s embarrassment was justified and we can still detect the pride of someone who had been educated following the nineteenth-century idea of classicism. With the ṛṣis , in fact, one has to go in quite another direction. Only the starting point is the same: the asat which Oldenberg translates as “non-being.” Now, if asat refers to the ṛṣis , the nonbeing would refer to a category of beings. These, in turn, would correspond with the “vital breaths,” prāṇas —and here we plunge into the realm of physiology. Moreover, nonbeing acts through the practice of tapas , the “ardor” that overheats consciousness. Too many palpable elements are attributed to this nonbeing. And above all: too many elements that then continue to appear and operate in the existent, in whatever exists. A network of cracks thus forms in it, as if to suggest that not everything that appears in the existent belongs to the existent. These metaphysical passages were not congenial to the West. Oldenberg could barely restrain his indignation: “The non-being starts to think, to act so readily, in spite of any Cogito ergo sum , like an ascetic preparing to perform some magic trick.” Oldenberg thought he was expressing a paradox, or even an absurdity. But his words could have been interpreted as a plain, accurate description. The ṛṣis watched him from high up in their stars, with that exasperating seriousness of theirs, more derisive even than sarcasm.

Читать дальше