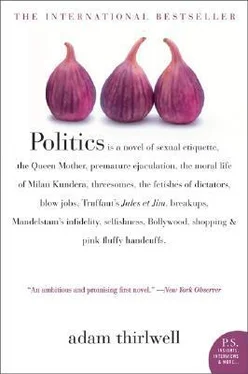

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was so glamorous, thought Moshe.

But this was the conversation. The conversation was not glamorous.

‘You won mind, will you, if I sleep in the middle tonigh?’ said Nana. ‘Jus for tonigh?’ asked puzzled Moshe. ‘Well I really can’t go on sleeping on the end,’ said Nana. ‘I wake up every morning when those men come for the bottles and then I can’t get back to sleep and then you get up and I’m sleepy all day. You don mind, dyou?’

And Moshe said ‘No, um, no, iss fine.’

Let me sketch out a quick diagram. Normally in bed it had been

Nana, Moshe, Anjali.

Now Nana wanted

Moshe, Nana, Anjali.

There was a subtle difference. Look who was next to whom. And Moshe understood this difference.

‘And also,’ she said, ‘there’s the window.’ ‘The window?’ said Moshe. ‘Yeah well I thought I’d get used to it I mean,’ said Nana, ‘I often sleep badly and maybe if. I don know. It’s just so cold.’ ‘Well less just stop sleeping with the window open,’ said Anjali. ‘From now on’, said Anjali, ‘iss shut. I prefer it shut too.’

Moshe stared at his steamed sea bass, wrapped in a wilted leaf.

‘Or you could sleep on the end and I’ll go in the middle,’ said Anjali. ‘If you go on the other end then you won’t be near the window.’

In Anjali’s revised diagram, the bedding arrangement went

Moshe, Anjali, Nana.

Nana liked this arrangement. Moshe did not like this arrangement at all.

Moshe leaned round and grabbed the wine from its silver stand behind him — which placed him full frontal with a black-and-white glossy of Elvis Costello. Elvis Costello, it turned out, was a regular at Le Caprice. He belonged to the glittering people. Moshe glared. He suddenly hated Elvis Costello. He hated glitzy happy people.

‘You never said,’ he said to Nana. ‘Did she say?’ he said to Anjali. ‘I don’t want you to,’ he said to Anjali and Nana.

And Nana said, ‘Well I could sleep on the futon tonigh, I suppose. I could jus sleep there.’ ‘The futon?’ said Moshe. ‘Why the futon? Why can’t we just shut the window?’ ‘We could shut the window,’ said Anjali, to Nana. ‘No no, why should Moshe be put out?’ said Nana to Anjali. ‘I mean it’s your flat isnit?’ she said to Moshe. ‘And you’ve always said you feel too hot with the window shut. So I should just sleep on the futon tonight.’ ‘Look,’ said Moshe, ‘akshully iss nothing. Really nothing. It’s not much of a sacrifice,’ grinned Moshe.

Nana said, ‘What did you say?’ She said, ‘Sorry I didn’t hear that. I thought my phone was ringing.’

He said, ‘It’s no sacrifice.’ But Nana said, ‘No no. Msleeping on the futon.’ ‘But wha if I say I don want you to?’ said Moshe. ‘I mean, you don like sleeping on your own. I know that. Why don you sleep in the bedroom with me and Anji? You don like it on your own.’

Two waiters were at the table beside them, crumbing down.

‘Look you’re being so silly,’ said Nana. ‘I mean. I spose I mean if Anjali prefers the window shut. I can sleep there with Anjali.’ ‘Bu bu, I just said we could close the window,’ said Moshe. ‘Oh babes,’ said Nana, ‘it’s not going to be for ever. I’m juss not sleeping,’ she said. ‘Za good idea,’ said Anjali.

‘Because when you get up you won’t have to mind about waking me up.’ ‘I wake you up?’ said Moshe. ‘Yeah, yeh,’ said Anjali. ‘In the mornings. When you climb over me.’

Nana shook the small ice cluttering her sparkling water. Moshe went to piss.

There was a man at a table near the stairs to the loos who had hair, thought Moshe, that he must have consciously designed himself. It had been tightly waved that morning with a round horsehair prickly brush. This man was showing photos to his companion, his male companion. His companion had a darkly yellow tan, glistening red dyed hair and gold Hugo Boss glasses with metal lines that swooped horizontally across and past the top. He had a wart and a moustache.

For some reason these two men made Moshe feel bitter. They made him feel very bitter. And although Moshe would not admit it, I can tell you the reason. It was because they were two men together. They had a homosexual look.

It is sad, but yes, one of the heroes of my book has become momentarily homophobic.

The men’s loos, however, were calmer. Luckily, there were no men. The urinals were one long urinal. This urinal had sloping frosted glass at its base, to allow the last weak and shaken drops to smooth away. Moshe bent backwards, scooping his penis out of his paisley-print boxer shorts. He tugged a pubic hair from his foreskin. Then he pissed. It felt nicer, thought Moshe, in the toilets, with the dimmed- down light and a black soft carpet. He looked at the rows of Armitage Shanks in discreet handwritten grey italics. He watched the way an empty circle spread around the point where his piss hit the porcelain. He shook the last weak drops away. Then he tucked his penis back in, it dribbled a little, zipped himself up, and ruffled his hair with water. The water fell out densely smooth with bubbles from the tap.

When he got back, the bill was on the table, in a leatherette wallet. Nana and Anjali were kissing. They were kissing little kisses.

Moshe, thought Moshe, had a problem.

7

Moshe’s problem was entertainingly similar to the problem of dissent in a capitalist society. As many left-wing critics have pointed out, it is very difficult to object to capitalism. One person who tried to explain this was Antonio Gramsci. Antonio Gramsci was an Italian Marxist. In 1926, he was arrested by the Fascist government, and put in prison. In 1928 he was sentenced to twenty years, four months, and five days. He died from a stroke in 1937. At this point, he was also suffering from arterio-sclerosis, a tubercular infection of the back, and pulmonary tuberculosis. However, it was not all bad. He had written his Prison Notebooks.

In these notebooks, Antonio outlined lots of theories. One of these theories was about how to be revolutionary when you live in a capitalist society. Revolution was tricky, thought Antonio, because of a thing called ‘hegemony’. Hegemony was ‘the combination of force and consent, which balance each other reciprocally, without force predominating excessively over consent. Indeed, the attempt is always made to ensure that force will appear to be based on the consent of the majority, expressed by the so-called organs of public opinion — newspapers and associations. ’

Phew.

Antonio, basically, was saying that no one ever cared when you disagreed with capitalism. The capitalists rigged it so no one noticed.

I, however, have a different theory why no one cares when someone attacks capitalism. You always look like a poseur. If you are rich, and you complain, people assume you are hypocritical. If you are poor, and you complain, people assume you are envious.

Similarly, if Moshe complained that a threesome was not ideal, you would assume he was being hypocritical. A grown man complaining about two girls in bed with him. The idea of it! But if he held your wrist, looked into your pretty blue eyes, and insisted that it was really not ideal, then you would assume that his objection to the threesome was pure jealousy. He was not getting the extraordinary sexual encounters, the dual sexual attention, that he had expected.

Sexually, I reckon you’d think, Moshe was poor.

8

A menage a trois, then, is a mixture of domestics and sex. It is much more similar to a couple than people think. It is just a more complicated couple. For example, you still have to buy milk. So, on a Saturday or Sunday morning, Nana and Anjali would walk to the cute dairy shop on Amwell Street.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.