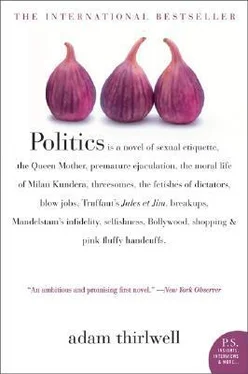

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Now, I am not sure that this actually happens in the film Jules et Jim. Personally, I never much liked the Jeanne Moreau character. I thought she seemed completely selfish and unattractive. But I like the point that Francois is making. I like the ideal.

Moshe dozed off. He listened to the city being busy. He gave Finsbury his blessing. Moshe blessed all the schnorrers.

The friendship of Jules and Jim had no equivalent in love. They accepted their differences. Everyone called them Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

Everything was ambiguous.

10

But what was Nana thinking? Was Nana happy too? Was this truly domestic bliss?

Look. Nothing has happened yet. The two girls kissed each other, sometimes, but nothing else.

Of course this was domestic bliss.

One evening, in bed with Moshe, on their own in Edgware, Nana was looking at the three Miffy postcards whose hanging had been curated by ten-year-old Nana, above her Ikea pine desk.

Miffy looking at an artist’s impression of a Mondrian.

Miffy looking in from a snowy window.

Miffy perched on the yellow crescent moon with yellow stars arranged around her in the dark blue sky.

And above the postcards there was Nana’s Babar poster — in his green suit and jaunty trunk, in whose nip a bowler hat fitted snugly.

That was the decor.

She was thinking that this was domestic bliss. And it was domestic bliss. Nana was happy. She was particularly happy tonight because her name, just for now, was Bruno. Yes, Bruno. And what did Moshe think about this? No no, not Moshe. Moshe also had a new name in bed. Newly christened by Nana, Moshe’s sex name was Teddy.

Alright?

Nana — Bruno. Moshe — Teddy.

Nana was happy. The girl scared by sex was confronting her fears. She had made up a scenario on her own. She was embarking on a life of perversion.

This was perversion?

Actually, I reckon it was perversion. There is something undeniably dirty about a twenty-five-year-old girl, in her childhood bedroom, being a ten-year-old boy. But it might be too dirty. Perhaps you need to keep sex in the realms of realism. If it is ridiculous, it becomes unsexual. It becomes bemusing.

Moshe was especially bemused. When Bruno told Teddy how much she loved Teddy’s babyish arms, their talcum- powdered smoothness, prosaic unimaginative Teddy replied that they were soft because he washed in the bath with E45. He had eczema. Soap was bad for eczema.

Moshe was not brilliant at this fantasy. He was not sure what he was meant to say.

Moshe and Bruno and Teddy and Nana listened to the rain.

‘I love lisning to the rain when I’m here in bed with you,’ said Bruno, wriggling, being Teddy’s best and closest friend. Bruno snuggled up, in her pyjama suit, cotton, with thin candystripes, flary at the ends. ‘You’re such a dorable creech,’ she said.

This was a fantasy. So I should explain the details of the fantasy. Teddy and Bruno are prep-school boys. But they are not at the same school. They develop their education at separate schools. But in the holidays they can chat again. They chat and while they chat they pretend that they have never lived apart, or known about any other boys. No, whatever may have happened at school, it was always the holidays they looked forward to. They are loving kids. Brought up in mutual luxury, Teddy and Bruno are best friends. They are soulmates. That was the fantasy. That was the backstory.

Teddy read The Little Prince to Bruno. And because, insisted Nana, they were very naughty, they read in the dark with a torch, tented in the duvet. Did this qualify as infantilism? wondered Moshe. If it did, he was unfussed. He just liked Nana being happy. He liked Nana being sexual.

Well, Moshe at least presumed that this would end up sexual.

So Teddy talked to Bruno. He told Bruno how he was finding sleep difficult. Matron was worried about him. He lay down and he could hear his heart in his head. He said there was also the asthma. He couldn’t breathe and it was asthma. Teddy confided in Bruno that every time when he was trying to make himself sleep, all he could imagine was that he was playing cricket. It sounded silly but it was true. He was batting. It was the same feeling as batting. It felt like he was standing there at the crease, hitting his bat in the mark, over and over, like they all do on TV. And his heart was all loud. Then Moshe went quiet. And Bruno piped up, ‘That’s an anxiety dream.’

He was a precocious kid, Bruno. He might have been seven but he had dipped into Freud.

They lay there in the bedroom with its chest full of toys. Inside the chest was a floppy busby, with fake plastic hairs, that Nana had received for being a brave soldier when she had her stitches in her forehead. All of Nana’s music certificates from the Associated Board — her piano and flute, grades one to eight — were framed on the wall. Some of the frames had plastic giltpainted moulded curls at the edges. Some of them were clipframes.

And, ‘Dyou remember’, said Teddy, ‘the way you used to fall off the side of the sofa, backwards onto the cushions, and you sort of felt your stomach disappear?’

Nana looked over Moshe’s shoulders with their few thin hairs. His breasts were curved and squashed together, ovals. She said, ‘Are you okay?’ And Teddy, wailing an interior opera of love and lust and overpowering sex, whispered to Nana, ‘Yehm fine.’ He slumped on to his back, then slumped his head over towards her. His chins creased together. Then he kissed her. She kissed him. Nana said, ‘Cool. If you say’s cool then it’s cool.’

If you had been down there on the street, beside a sleeping policeman, in the sodium fuzzy light, then nothing would have been obvious. You would not have got, say, a snapshot of Nana in her unbuttoned pyjama top, with just the merest slope of her left breast visible. No. You would have seen a bedroom. You would have seen lamplight. You would have seen a haven.

It was domestic bliss.

How, thought Moshe, how can you shift this from fondness to filth?

It was tricky. Neither of them were boys. Neither of them were gay. So filth, in the circumstances, was difficult. They had not had the practice at youthful gay sex.

He said, ‘Should I touch you?’ Because Teddy and Bruno, after all, were homosexual. He said, ‘Do you want me to touch you?’ And Moshe put his hand where Bruno’s minute penis was. Nana held his hand. She held it there. She said, ‘Oh no.’

When a prep-school boy says no, he means yes.

11

I can imagine that at this point you may be feeling a little confused. You may have a list of questions. Why are they not complaining? Why are they not wishing they were in a simple relationship? Why is Moshe playing along with this Teddy and Bruno scenario? And why is he not complaining that Nana is flirting with another girl? And why is Nana not complaining that Moshe is never jealous?

They are not complaining because complaining is difficult. They are not complaining because they are both happy to compromise. Complaining makes them more unhappy than compromising.

I know you are not convinced by this. You are unpersuaded. Where is the realism? you say. Where is the accuracy of the European novel? Where is the truth to nature of Balzac or Tolstoy?

Well, let us think about a European novelist. I am going to tell you a small story about the life of Mikhail Bulgakov. Bulgakov was a satirical novelist and playwright in Stalinist Russia.

On 28 March 1930, Mikhail wrote a letter to the government of the USSR.

12

After all my works were banned, many citizens who know me as a writer could be heard all offering the same advice:

Write a ‘Communist play’ and also send a repentant letter to the government of the USSR, recanting the views I had formerly expressed in my literary works, and giving assurances that henceforth I would work as a fellow-travelling writer who was devoted to the idea of Communism.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.