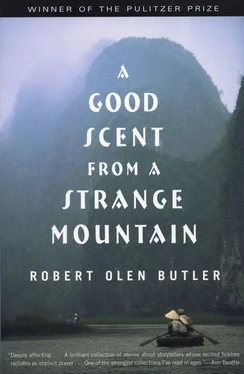

When we all lived in Saigon at last, my grandfather discovered the bird market on Ham Nghi Street and he would take me there. Actually, in the street market of Ham Nghi there were animals of all kinds — dogs and monkeys and rabbits and turtles and even wildcats. But when my grandfather took my hand and said to me, “Come, little one,” and we walked down Tr  n Hu’ng Ð

n Hu’ng Ð  o, where our house was, and we came to Hàm Nghi, he always took me to the place with the birds.

o, where our house was, and we came to Hàm Nghi, he always took me to the place with the birds.

The canaries were the most loved by everyone who came to the market, and my grandfather sang with them. They all hopped to the side of their cages that was closest to my grandfather and he whistled and hummed and even sang words, songs from the North that he sang quite low, so that only the birds could hear. He did not want the people of Saigon to realize he was from the North. And the canaries all opened their mouths and the air filled with their sounds, their throats ruffling and puffing, and I looked at my grandfather’s throat to see if it moved the way the throats of these birds moved. It did not move at all. His skin was slack there, and in all the times I saw him charm the birds, I never saw his throat move, like he didn’t really mean the sounds he made. The people all laughed when they saw what he could do and they said that my grandfather was a wizard, but he would just ignore them.

The canaries seemed to be his favorite birds on Hàm Nghi, though he spent time with them all. The dark-plumed ones — the magpies and the blackbirds — were always singing on their own, especially the blackbirds with their orange beaks. My grandfather came near the blackbirds and they were gabbling among themselves and he frowned at them, like they were fools to be content only with their own company. They did not need him to prompt their songs. He growled at them, “You’re just a bunch of old women,” and we moved on to the doves that were big-eyed and quiet and he cooed at them and he told them how pretty they were and we looked at the moorhens, pecking at the bottoms of their cages like chickens, and the cranes with their wonderful necks curling and stretching.

We visited all the birds and my grandfather loved them, and the first time we went to Hàm Nghi, we ended up at the cages crowded with sparrows. He bent near their chattering and I liked these birds very much. They were small and their eyes were bright, and even though the birds were crowded, they were always in motion, hopping and fluffing up and shaking themselves like my vain friends. I was a quiet little girl, but I, too, would sometimes look at myself in a mirror and primp and puff myself up, even as in public I tried to hold myself apart a little bit from the other girls.

I was surprised and delighted that first day when my grandfather motioned to the birdseller and began to point at sparrows and the merchant reached into the cage and caught one bird after another and he put them all into a cardboard box. My grandfather bought twelve birds and they did not fly as they sat in the box. “Why aren’t they flying?” I asked.

“Their wings are clipped,” my grandfather said.

This was all right with me. They clearly weren’t in any pain and they could still hop and they would never flyaway from me. I wouldn’t even need a cage for my vain little friends.

I’m sure that my grandfather knew what I was thinking. But he said nothing. When we got home, he gave me the box and told me to take the birds to show my mother. I found her on the back stoop slicing vegetables. I showed her the box and she said that Grandfather was wonderful. She set the box down and told me to stay with her, I could help her. I crouched beside her and waited and I could hear the chattering of the sparrows from the box.

We had always kept chickens and ducks and geese. Some of them were pecking around near us even as I crouched there with my mother. I knew that we ate those animals, but for some reason Hàm Nghi seemed like a different place altogether and the sparrows could only be for song and friendship. But finally my mother finished cutting the vegetables and she reached into the box and drew out a sparrow, its feet dangling from the bottom of her fist and its head poking out of the top. I looked at its face and I knew it was a girl and my mother said, “This is the way it’s done,” and she fisted her other hand around the sparrow’s head and she twisted.

I don’t remember how long it took me to get used to this. But I would always drift away when my grandfather went to the sparrow cages on Hàm Nghi. I did not like his face when he bought them. It seemed the same as when he cooed at the doves or sang with the canaries. But I must have decided that it was all part of growing up, of becoming a woman like my mother, for it was she who killed them, after all. And she taught me to do this thing and I wanted to be just like her and I twisted the necks of the sparrows and I plucked their feathers and we roasted them and ate them and my grandfather would take a deep breath after the meal and his eyes would close in pleasure.

There were parrots, too, on Hàm Nghi. They all looked very much like Mr. Green. They were the color of breadfruit leaves with a little yellow on the throat. My grandfather chose one bird each time and cocked his head at it, copying the angle of the bird’s head, and my grandfather said, “Hello,” or “What’s your name?" — things he never said to Mr. Green. The parrots on Hàm Nghi did not talk to my grandfather, though once one of them made a sound like the horns of the little cream and blue taxis that rushed past in the streets. But they never spoke any words, and my grandfather took care to explain to me that these parrots were too recently captured to have learned anything. He said that they were probably not as smart as Mr. Green either, but one day they would speak. Once after explaining this, he leaned near me and motioned to a parrot that was digging for mites under his wing and said, “That bird will still be alive and speaking to someone when you have grown to be an old woman and have died and are buried in the ground.”

I am forty-one years old now. I go each day to the garden on the bank of the bayou that runs through this place they call Versailles. It is part of New Orleans, but it is far from the center of the town and it is full of Vietnamese who once came from the North. My grandfather never saw the United States. I don’t know what he would think. But I come to this garden each day and I crouch in the rich earth and I wear my straw hat and my black pantaloons and I grow lettuce and collards and turnip greens and mint, and my feet, which were once quite beautiful, grow coarse. My family likes the things I bring to the table.

Sometimes Mr. Green comes with me to this garden. He rides on my shoulder and he stays there for a long time, often imitating the cardinals, the sharp ricochet sound they make. Then finally Mr. Green climbs down my arm and drops to the ground and he waddles about in the garden, and when he starts to bite off the stalk of a plant, I cry, “Not possible” to him and he looks at me like he is angry, like I’ve dared to use his own words, his and his first master’s, against him. I always bring twigs with me and I throw him one to chew on so that neither of us has to back down. I have always tried to preserve his dignity. He is at least fifty years older than me. My grandfather was eighteen when he himself caught Mr. Green on a trip to the highlands with his father.

So Mr. Green is quite old and old people sometimes lose their understanding of the things around them. It is not strange, then, that a few weeks ago Mr. Green began to pluck his feathers out. I went to the veterinarian when it became clear what was happening. A great bare spot had appeared on Mr. Green’s chest and I had been finding his feathers at the foot of his perch, so I watched him one afternoon through the kitchen window. He sat there on his perch beside the door of the back porch and he pulled twelve feathers from his chest, one at a time, and felt each with his tongue and then dropped it to the floor. I came out onto the porch and he squawked at me, as if he was doing something private and I should have known better than to intrude. I sat down on the porch and he stopped.

Читать дальше

n Hu’ng Ð

n Hu’ng Ð  o, where our house was, and we came to Hàm Nghi, he always took me to the place with the birds.

o, where our house was, and we came to Hàm Nghi, he always took me to the place with the birds.