Then he turned the cows home, judging the movement of the storm expertly, timing it even as he ate carefully around the worm lodgement in the plums, brought the cows up to the shelter of the old gray shed just as the first wind and heavy thudding raindrops hit.

The weather passed, the new days sparkled dry, too dry, too much dust, the land too feeble for anything but sunflowers and cockleburs.

She went away one day, came out, closed the door and walked down the lane, tall figure, angular, sharp as a nose, darkly dressed, gray-black skirt, black hat, not walking so much as sweeping along for he could not see the lower third of her from over the stunted sweet clover by the fence. She waited a long time at the mailbox and then the Liles came by in the old Chevy and picked her up.

He went down through the clover patch (the nurse crop of oats had been strangled already) zig-zagging a little almost unconsciously for he knew how the clover could lie over and leave a distinct track. At the chicken coop there was the old hen and two half-feathered chicks. Two gone, he thought.

The air was motionless, entirely. He waited, conscious suddenly of the totality of silence, held his breath and listened, not even the murmur of flies. It was as if he were on another planet, divorced from everything he knew. The hot afternoon burned without sound, without motion. Even the chickens spread their drooping wings in the tiny shade, their beaks locked open, only their throats working.

He had one weak urge to shout, to interrupt that silence, change it somehow, to powerfully alter for a moment this quiet deadness, but the wish boiled off, leaving him impotent and hot.

In darkness of the lean-to beside the house a glimmer of yellow-greenish light, opening, shut. The boy backed away, moving he realized even then with a drugged sluggishness that he would remember, came forward a step, forced himself forward. The oil eyes watched him from under there, open, shut, with a slow mysteriousness as if too under a spell. A cat. He reached in, felt the fur, hand fastened on the acquiescent neck, lifted the cat out, neither cat nor kitten, halfway between, gray, color of ashes, brought it to his curved arm. It sat calmly, turned its head a little.

“Where did you get that?” the mother asked in the evening when he came up from the barn.

“I found it in the pasture,” he said.

“Oh, I don’t like cats around,” she said.

“It’ll catch mice,” he said.

“See that it stays outside,” she threatened.

That determined him. He snuck it in, put it in a box by his screenless window, so that it could go in and out.

On the hot nights he could hear its passage, and sometimes if he awoke he could see the slivers of eyes in the darkness, opening, closing, slowly, very slowly, giving him a peculiar chill.

Perhaps he would have been startled, even afraid, if he had not always been pleased, when thinking of it, at defying his mother’s command. The cat was there, inside the house, as he wished.

In the daytime it disappeared, where to he did not know. Saw it from time to time beneath the porch or in the loft of the barn, but usually not at all.

He went regularly to his duty of keeping his eye on the cows. The afternoons swooned with heat. The sun sat in its haze, too bright to look at. His short shadow was noiseless as he, through the thickets by the dry dead stream, through the powdery dust on the path the cows took. The milkweed that he touched filtered pollen upon his hands, the feeble tree-branch posts leaned, drowsed in drunken posture held up by the rusted wires. The cows baked beneath a cottonwood’s shade, lashing flies, eyes closed, stomping hoofs against the flies, choking on cuds.

He could hear the sound and he shivered, truly shivered, skin cold as touching a sweating arm. She was singing. Words too distant for him to understand, high-pitched, cracking almost. Nothing musical, even he who knew nothing of music but a few hymns and the schoolroom mutterings to the teacher’s piano, knew that this tuneless screeching was a following of some melody he did not know.

He peeped past a post, looked between bunches of sweet clover, yellow blossoms wilted in the motionless heat. He went on his hands and knees, the pollen falling on him, careful not to move the bunches if he could, no wind, no other motion than himself.

She had stopped singing. He waited, looking through the great bunches of clover, webbed and tight and defensive. He was no more than forty feet from the little shanty, the weathered boards stiff and black. Shrilly she started again; a yelp, shriek of sound, stopped again. Language unknown to him.

She came through the doorway, opening into darkness, her movement sending him into a tight, sprung posture, holding all breath, feeling ooze of sweat from his face. She dumped a pan of something, potato peelings, whatever, the one hen came to peck, and one cat too, his cat he believed. And looked again at her. Amazed at how old she seemed, white hair he had only slightly noticed that one time he’d seen her, hair undone, wisps of white down her face as if a white liquid poured over her head, congealed there. Wrinkled, wrung face, pinched mouth. Same angular body, long, long, rising up.

She sang, stood there and shrieked sounds, six or seven words he did not understand, popped the bottom of the dishpan with her hand, freeing the last peel or two, went in again, was silent.

The boy watched the cat glide up, lift one forepaw, sniff at the peelings, sit down, lick itself. His own cat, he believed, although he could not be certain, believed it was his, in that heat nothing registering right, all uncertain for him like unsteady imaginings or dreams.

He went the way he had come.

“Oh, I don’t like her,” the mother said to the Nystroms next time they went up the hill to visit. “I saw her in town one day, and she looked just crazy.” She gave a shudder to indicate her distaste.

“She goes in with the Liles,” old man Nystrom said, waggling his big head. “They say sometimes her bag of groceries is as big as a candy sack.”

“Funny one,” Nystrom’s wife said. “Always acted strange. I went over there once and she wouldn’t even let me in the house.”

“Na,” the mother said.

“Some say she’s done peculiar things.”

“I’ve heard her sing,” old man Nystrom said.

“Sing!” the mother cried.

The big man grinned. Yellow, crooked teeth. Big mean blue eyes. “Oh ya, sometimes the whole day through. I’ve heard her when I stopped the tractor.”

“And there are times when she’s not around for months,” the oldest son said.

“Oh ya, that too,” Nystrom said.

“They say she’s a witch,” Nystrom ‘s second son said.

They all laughed at that.

Mrs. Nystrom the loudest. “Kept my kids scared for years, telling about the Widow. They would sure mind then.”

The mother hissed with laughter.

“Ya, she’s kept the kids toeing the line for years over that. Only way they go over there is on a tractor,” old Nystrom said.

“Wouldn’t catch me gettin offen it neither,” the older son said, sucking in his nostril and giggling.

“She is a sight to see sometimes, although some say she was a pretty woman years back,” Mrs. Nystrom said. “She’s not a witch. Isn’t any such thing.”

“Shoulda told us that years before,” the oldest son said, whickering.

“Let’s see, what you need to be a witch?” Nystrom asked. “Pin cushion, baby fat, and a fire. And a… a cat. Yeh?”

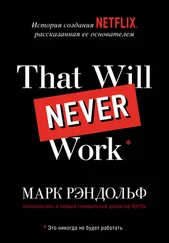

Читать дальше