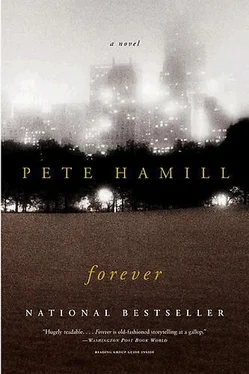

Pete Hamill - Forever

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Forever» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, ISBN: 2008, Издательство: Paw Prints, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Forever

- Автор:

- Издательство:Paw Prints

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:9781435298644

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Forever: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Forever»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Reprint. 100,000 first printing.

Forever — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Forever», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“And the battle might never be fully won,” he said, turning to blow loudly into his soiled, pebbly handkerchief. “We each have the obligation of eternal vigilance! Watch the man next door!”

Cormac was certain that Robinson glanced at him while speaking these words, but he absorbed the glance in his newly chosen role of spy. This was a secret personal performance that transformed many of his days into exciting patrols of enemy territory. He covered himself so well that to all his schoolmates he remained young Robert Carson, gifted at writing and drawing, a poor fellow whose mother had died, but who was, like each of them, an heir to the grandeur of English civilization. There were no questions from his friends, no suspicions (uttered or suggested) that he might actually be Cormac O’Connor, son of Fergus. The Rev. Robinson might have had his suspicions about John Carson, but he never transferred them to the blacksmith’s son. If anything, after that first taming year when he used the Punisher so freely, Rev. Robinson seemed to approve Robert’s growing mastery of ritual speeches about the moral missions of English monarchs and the debased perfidy of the Catholic Spanish and French. Cormac had a good memory and as Robert Carson he had the ability to infuse his speeches with emotion. Without a plan, the boy was serving a partial apprenticeship as an actor.

This personal form of espionage required much discipline, because unlike his schoolmates, Cormac O’Connor was learning other histories. To begin with, Irish history. “Our present,” his father said, “is also our past.” They talked much about the Penal Laws, which still existed today, in their Ireland; the O’Connors were saved from their brutality by the success of their disguises, by being Carsons. But the vicious Penal Laws were destroying thousands of innocent Catholic men, women, and children, those without disguises, those too full of defiance and pride, and were rooted in the immediate past.

“They were imposed,” Fergus O’Connor explained, “only thirty years before your birth, Cormac, and are one reason why you’re called Robert and I’m called John. They are the creation of the kind of men who take, sell, and keep slaves.”

Under these laws (which Robert heard recited at St. Edmund’s too, as the rules of eternal vigilance), no Catholic could vote or hold public office. No Catholic could study science or go to a foreign university. Only Protestants could do such things. No Catholic could buy land or even lease it. No Catholic could take a land dispute to court. If a Catholic owned land from the time before the Penal Laws, he couldn’t leave it as in olden times to his oldest son; he must divide it among all his children, so that each plot would become smaller and smaller, and poverty would be guaranteed within three generations.

The most absurd of the Penal Laws stated that no Catholic could own a horse worth more than five pounds. Any Protestant could look at a Catholic’s horse, say it was worth six pounds, or thirty pounds, or a thousand pounds, and take it from him on the spot. The Catholic had no right to protest in court. In a country of great horses and fine horsemen, the intention was clear: to humiliate Catholic men, to break their hearts.

“If you can break a man’s heart,” Da said, “you can destroy his will.”

That was why they must remain Carsons to everyone they ever met. When they rode Thunder through country lanes or city streets, they must be Protestants. “Even poor Thunder must be a Protestant horse,” his father said, and laughed in a dark way. But he’d told his son that they were not Catholics either, so what did they have to fear? “Sick bastards,” Fergus O’Connor said. “In this country, they think that if you’re not Protestant then you must be Catholic, even if you’re not. It’s a sickness, a poison of the brain.”

And so Fergus began telling his son the longer story too, the one not told in school. They were part of that story, as the hidden grove was a defiant remnant of unconquered Ireland. Unconquered by either Rome or London. In the schoolroom at St. Edmund’s, the boy learned the names of English kings and English heroes. He read the Magna Carta. He recited English ideals. But as his father told him the story of Ireland, his mind also teemed with Celts and Vikings, informers and traitors, and murder after murder after murder.

As Fergus O’Connor ate greedily each evening (his manners grown coarser after the death of his wife), he sketched the history, relating the brutal story of Oliver Cromwell and the vast slaughters of unarmed Catholics, and then leaped backward in time to the arrival of Strongbow on May 1, 1170, as the result of the treachery of Irish nobles. He told his son about how “that bitch” Elizabeth I was really a heartless killer, and how her father, Henry VIII, encased in fat and pearls, was even worse, killing two of his six wives, along with thousands of Irishmen, while imposing his own version of Christianity on the islands. Such words always came from Fergus with a sense of growing outrage, as if each new telling of the tale drove fury through his blood. For Cormac, the Irish tales were like those in the Bible, full of heroism and cowardice and martyrdom—and, too often, exile. And in the Irish story, the result was always the same: the English stealing Ireland for themselves, acre by acre, for its wood and its crops and its cheap labor, and for its fine horses too, while insisting that this grand robbery was something noble.

Cormac heard his father explain how the unarmed Ulster Irish were beaten back off the good land into the rocky hills and the stony mountains, the good land handed to the likes of the whoremaster Chichesters, while poor Protestant settlers were brought from Scotland to work the land and pay rents to the English. “They were made into slaves,” Da said, “and thought they were free.” After a while, when the British perfected the use of religion as an excuse for cruelty and theft, the Irish began to think that being Catholic was the same as being Irish, which of course it wasn’t.

“The Irish were here before Jesus Christ was even born,” he said. “So were their gods.”

The evening monologues of Fergus O’Connor were in startling contrast to his silence when he was playing John Carson. The words came in streams, rising and falling, emphasized with his long fingers, or by hands balled into fists. Still, in all that he said to his son, he insisted there were men in Ireland who cared for true justice.

“There’s a fellow in Dublin, the Dean, they call him,” he said one night. “Jonathan Swift. You must read his Drapier’s Letters, son. I have them in a bound book, hidden out in the stable. He’s a man with justice in his heart. A Protestant, but an Irishman first. And you must begin reading the newspapers. The News-Letter here is run by fair men. The Dean writes for the Dublin Journal, and I have some of those hidden here too.”

“Why do you hide them, Da?”

“Because of the bloody injustice here, lad. Some writers expose the injustice, and just reading about it will make you a suspect. And whenever there’s trouble in Ulster, every suspect dies.”

“Are we suspects, Da?”

The older man paused for a long moment.

“I think we are,” he said.

16.

On Sundays, father and son trudged to St. Edmund’s to inhale the odors of an orderly piety. Each wore his mask. For a solemn hour, Fergus and Cormac O’Connor played John and Robert Carson. An hour later, all sermons absorbed, all visions of Hell behind them, they mounted Thunder and trotted into the glens behind the Black Mountain. There, beyond observation, Sunday after Sunday, with a kind of religious intensity, the father showed his son the power of the sword.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Forever»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Forever» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Forever» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.