“I had some fun there,” he said later, about Hoboken. “I had some misery too.”

There was much misery in the land now, and it was spreading. Hoovervilles began appearing along the New Jersey and New York waterfronts, clusters of crude shacks that housed the Depression homeless. In 1931, with 4 million Americans now unemployed, there were reports of food riots in Oklahoma and Arkansas and a riot over jobs in Boston. Through all of this, Frank Sinatra was sitting in the dark, watching James Cagney hit Mae Clarke in the face with a grapefruit in The Public Enemy and Bela Lugosi sucking blood in Dracula . He no doubt talked with his friends about Al Capone going to prison for tax evasion and Legs Diamond being shot to death in a hotel room in Albany; his youth was lived in the great era of the tabloid newspaper. But he wasn’t sure how he fit in. Anywhere.

“I’d rather do time in Attica than be fifteen again,” he once said. “I didn’t know whether I was coming or going.”

That year of 1931 the Sinatras moved again, this time into their own home, which they bought for $13,400, a considerable sum in that Depression year. They had, at last, their piece of the American earth. No more paying rent. No more hassles with landlords. Now they had a three-story home at 841 Garden Street, complete with steam heat, a bathtub, and a finished basement. A house that rode high over the street. Dolly was more active politically than ever before, operating as the ward boss. She helped the Depression casualties as best she could, laying out spreads of food, trying to find work for those who had lost their jobs. She tried to persuade some despairing Italians that they should not go home, that Benito Mussolini had not created paradise in his Fascist Italy; some departed anyway. During this period Frank Sinatra began to invent his dream.

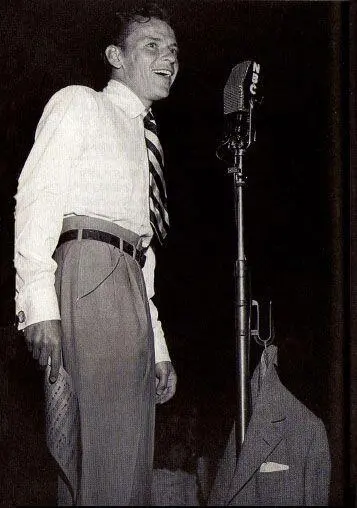

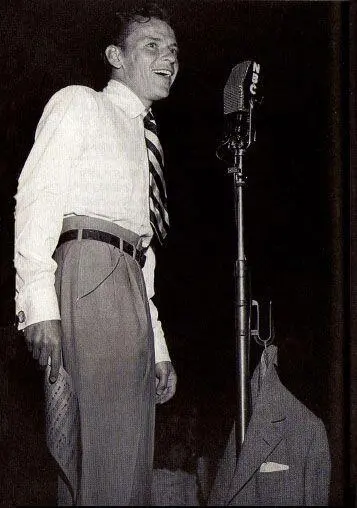

“I was always singing as a kid,” he said. “But it was never serious. I’d sing at the bar, you know, and get a round of applause, led by Dolly. There was a player piano in the joint, with music on a roll. I’d sing and they’d give me a hand, and sometimes a nickel or a quarter. It wasn’t that I was so great. Mainly, they cheered because I could remember the words.”

But in Dolly’s saloon the only child was discovering that he needed an audience. If his mother whacked him and then hugged him, then he would present himself to strangers. If he was good, if he could be more than just a kid who remembered the words, they certainly wouldn’t whack him. Their cheers would make him feel valuable, and connected to others. Maybe then Marty and Dolly would recognize his existence in some new way, and if they didn’t, the hell with it. In junior high school he joined the glee club. He listened constantly to the radio, bought sheet music (he never learned to read music), and memorized lyrics. He was given a ukulele by his mother and would play and sing with his friends on the street. At the movies, he saw that singers always got the girl. On the radio he heard Rudy Vallee and Russ Columbo and Dick Powell. And then he discovered Bing Crosby.

“The thing about Bing was, he made you think you could do it too,” Sinatra said, half a century later. “He was so relaxed, so casual. If he thought the words were getting too stupid or something, he just went buh-ba, buh-ba, booo. He even walked like it was no effort. He was so good, you never saw the rehearsals, the effort, the hard work . It was like Fred Astaire. Fred made you think you could dance too. I don’t mean just me. I mean millions and millions of people. You saw Fred dance, you heard Bing sing, and it was like you were doing it. After a movie you saw guys in the street dancing. You heard them singing to their girls. It was amazing, what those men did, Bing and Fred. Some people, they danced and sang right through the fucking Depression. Every time Bing sang, it was a duet, and you were the other singer.”

Young Frank Sinatra began to develop a theatrical personality to go with his singing. His mother arranged for credit at a clothing store, and he soon had so many pairs of slacks that he was nicknamed Slacksey O’Brien. He owned a phonograph and a growing collection of records. When he was sixteen, his father allowed him to use the family Chrysler, and he would take his friends for rides, often wandering as far as Atlantic City. The new house even had the ultimate luxury: a telephone. Frank Sinatra did not have a hard Depression.

“We never went hungry,” he said later. “It wasn’t luxury, but it wasn’t bad.”

He began to live a split life. On the street he donned the mask of the wise guy, an image fed by the gangster films that had taken the place of westerns in creating the myth of the American outsider. He posed like Cagney, like Edward G. Robinson. He dressed “sharp.” He jingled change in the pockets of his slacks. He cursed. He talked tough. He showed his friends he would fight if he had to, and what he lacked in street-fighting talent, he made up for with courage. On the street he was developing an act, a disguise that would protect him from the world while asserting his presence in his own small piece of that world.

Alone, he was conceiving a different vision, and it had nothing to do with the neighborhood streets of Hoboken. As a teenager, he must have realized that loneliness might be his lot, but even then he refused to accept it as inevitable. Across a lifetime he would make many attempts to relieve loneliness, submerging it in marriages and love affairs, hard-drinking camaraderie, bursts of movement and action and anger, but the only thing that ever permanently worked was the music. And when he was an adolescent, a combination of words and music began to create the vision of escape. From solitude. From obscurity. From the polarities represented by Marty and Dolly Sinatra. Sometimes he would wander down to the waterfront alone, past the Hoovervilles, past the rusting tracks of the railroad spurs, out to the edge of the piers. There, he would gaze across the harbor at New York, the spires of its skyline rising toward the sky.

THE BIRTH OF A CREATURE OF HUMAN FANTASY, A BIRTH WHICH IS A STEP ACROSS THE THRESHOLD BETWEEN NOTHING AND ETERNITY, CAN ALSO HAPPEN SUDDENLY, OCCASIONED BY SOME NECESSITY. AN IMAGINED DRAMA NEEDS A CHARACTER WHO DOES OR SAYS A CERTAIN NECESSARY THING; ACCORDINGLY THIS CHARACTER IS BORN AND IS PRECISELY WHAT HE HAD TO BE.

— LUIGI PIRANDELLO, 1925

“WHAT THE FUCK WAS THAT?”

— BENNY GOODMAN, his back to the audience at the New York Paramount, as Frank Sinatra made his entrance and the fans roared, December 30, 1942

HIS FINEST ACCOMPLISHMENT, of course, was the sound. The voice itself would evolve over the years from a violin to a viola to a cello, with a rich middle register and dark bottom tones. But it was a combination of voice, diction, attitude, and taste in music that produced the Sinatra sound. It remains unique. Sinatra created something that was not there before he arrived: an urban American voice. It was the voice of the sons of the immigrants in northern cities — not simply the Italian Americans, but the children of all those immigrants who had arrived on the great tide at the turn of the century. That’s why Irish and Jewish Americans listened to him in New York. That’s why the children of Poles in Chicago, along with all those other people in cities around the nation, listened to him. If they did not exactly sound like him, they wanted to sound like him. Frank Sinatra was the voice of the twentieth-century American city.

In life even the mature Sinatra would sometimes speak in the argot of the street. He could be profane, even vulgar. The word them could become dem, and those could become dose . It depended on the company. But in the songs the diction was impeccable. The children of the Italians, the Irish, and the Jews wanted to believe that they could express themselves that way, and many of them did. In my Brooklyn neighborhood, many of us understood that we were not prisoners of the Brooklyn accent, because Sinatra’s singing refused to use it. And he was like us. His diction was something that Sinatra learned early, from the movies.

Читать дальше