Patriotism was soon redefined. It was no longer enough to love the United States; to prove your American identity, you also had to hate other countries and “foreign” ideologies. In its preparations for war, the administration of Woodrow Wilson had organized a brilliant propaganda campaign whose intention was to meld various nationalities into one. The first enemy was the Hun; the second was the Red. The Hun bayoneted babies. He executed nurses. He was the enemy of democracy everywhere, and the British and French were its defenders (this was news to the millions who lived in their colonies, of course, but logic was an early casualty of the war). Tin Pan Alley was enlisted for the duration, under the command of George M. Cohan, who created the patriotic music that is still played to this day. When the United States declared war on April 6, 1917, there was an orgy of flag-waving celebration, rallies, and parades. Even Enrico Caruso made a recording of Cohan’s “Over There.” There were no songs about chasing Reds.

Frank Sinatra would remember none of this. All he remembered was the victory parades. But the immense slaughter of the Great War had broken many things in the world. The United States would assume much greater powers, acquire more swagger, and in the eyes of many be riddled with greater hypocrisies. The Golden Door, which had welcomed so many millions of immigrants, would slam shut. Those who believed in the old way would receive no reinforcements. Now there was only the new way. And Frank Sinatra would be part of it.

FOR HOW DOES ANY MAN KEEP STRAIGHT WITH HIMSELF IF HE HAS NO ONE WITH WHOM TO BE STRAIGHT?

— NELSON ALGREN,

The Man with the Golden Arm

As an artist, Sinatra had only one basic subject: loneliness. His ballads are all strategies for dealing with loneliness; his up-tempo performances are expressions of release from that loneliness. The former are almost all fueled by abandonment, odes to the girl who got away. The up-tempo tunes embrace the girl who has just arrived. Across his long career, Sinatra did many variations on this basic theme, but he got into real trouble only when he strayed from that essentially urban feeling of being the lone man in the crowded city. He is at his most ludicrous in the film clip where he sings “Ol’ Man River” in a white tuxedo; he is at his most self-parodic in the part of the Trilogy album when he addresses a hymn to himself while a celestial background choir chants, “Sinatra! Sinatra!” Like all great stars, he was susceptible to the twin temptations of flattery and mythomania. But in the end, his finest work takes place at the midnight hour, when he tells the bartender that it’s a quarter to three and there’s no one in the place except you and me.

There could have been no other subject, of course, if Sinatra was to draw, like any major artist, on the emotions that he felt most deeply. Frank Sinatra was the first and only child of Dolly Sinatra. After the panic, horror, and physical damage of her son’s birth, she was unable to bear any more children. So Frank grew up as a lone child in a neighborhood of large families. That special condition was to mark his psyche as surely as the doctor’s forceps marked his face.

“I used to wish I had an older brother that could help me when I needed him,” he said. “I wished I had a younger sister I could protect. But I didn’t. It was Dolly, Marty, and me.”

The first child in immigrant families is also the first American, the one who truly begins the American part of the family saga. But an only child is in a position of greater isolation than most such children; he or she has no older brothers and sisters who can serve as guides; there are no younger siblings who can benefit from hard-earned knowledge. The American child is forced to tell what he knows to strangers. That is, he must go beyond the older people in his life, and find an audience. And he (or she) must find ways to deal with the deepest loneliness: the hours after the audience is gone and the boy closes the door to his room.

“There’s nothing worse when you are a kid than lying there in the dark,” he said to me once. “You got a million things in your head and nobody to tell them to.”

Frank Sinatra’s personal solitude was compounded by the nature of his parents. His father lived much of his life in a dark pool of silence. “He was a nice guy,” Sinatra said later. “I loved him. But the man was the loneliest guy I ever knew.” The boy also must have been uneasy trying to separate his father, Marty Sinatra, from the public person called Marty O’Brien. A private Italian and a public Irishman. A man who was alone at a kitchen table but known publicly to dozens of people on the street. In those days it would not have been strange for a boy to believe that the man was ashamed of being Italian. His father’s split identity surely explains, at least in part, Sinatra’s later vehemence about keeping his own name when Harry James wanted to change it.

“He wanted me to call myself Frankie Satin! ” he remembered many decades later, chuckling as he spoke. “Can you imagine? Is that a name or is that a name? Now playing in the lounge, ladies and gennulmen, the one an’ only Frankie Satin. … If I’d’ve done that, I’d be working cruise ships today.” He laughed, and then turned serious. “Besides, one fake name in the family was enough.”

The boy (who was, by the way, christened Frank, not Francis Albert, at St. Francis Roman Catholic Church in Hoboken on April 2, 1916) also had to deal with the absence of Dolly Sinatra. She lived at home and was house proud, but she was gone throughout most of the day, working at a chocolate shop, leaving the boy Frank in the care of his grandmother, Rosa Garavente. In the evenings Dolly’s energies were increasingly absorbed by the duties and rewards of local politics.

She was a Democrat, of course, because the Republicans then, as now, were believed to be anti-immigrant but also because in that part of New Jersey, Democrats had power. She eventually became the leader of the Third Ward in Hoboken’s Ninth District, able to deliver a minimum of six hundred votes to the Hudson County machine run by Boss Hague. To such political activists, ideology was much less important than the practical benefits that came from belonging to a powerful group. You could reward your friends. You could punish your enemies. Or at least hold them back. For many Italians and their children, holding off enemies was a serious matter. By the time Frank Sinatra was ten, there were millions of Ku Klux Klan members across the nation, 40,000 in New Jersey alone; a Klan branch even operated in Hoboken, under the leadership of King Kleagle George P. Apgar, and the haters in the white sheets made no secret of their contempt for Italians. Through politics, Dolly could enlist the law on the side of the Italians in her ward. But even before issues of common defense, she was absorbed with the more mundane concerns of her vocation: the granting of favors. I mentioned once to Sinatra the saying of Boss Tweed: “It’s better to know the judge than to know the law.”

“That could’ve been my mother talking,” he said, and shook his head in a fond way. Alas, knowing the judge didn’t help Dolly when one of her brothers was arrested in 1921 for his part in an armed robbery that left a Railway Express worker dead. He wasn’t the shooter, but he drove the getaway car and was sentenced to ten to fifteen years at hard labor. It could have been worse; he could have been executed.

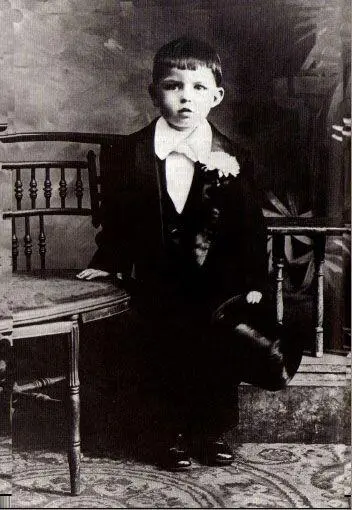

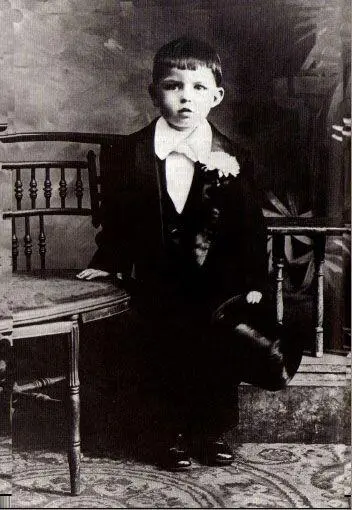

Even though she was seldom around, Dolly would be a permanent force in her son’s life. As a very young child, Sinatra was often dressed as a girl; Dolly had wanted a girl, bought clothes for a girl, and wasn’t going to waste them. As he grew older, she dressed him with pretensions toward elegance. It was necessary to honor the tradition of la bella figura, dressing as a form of show. There is a studio photograph of the boy at about age five, in full formal dress, with a four-in-hand white bow tie and a carnation pinned to his lapel. He is holding a top hat, one hand resting casually on the seat of a studio chair. His face is both intelligent and tentative, absorbed in the process of the photograph, looking warily at something, or someone, slightly to the left of the photographer. Probably it was Dolly Sinatra. Probably she was giving him stage directions. The photograph, after all, was not for him. It was for her.

Читать дальше