‘It’s coming. It’s coming tonight.’

He drew in breath to speak but what came out was something like a sneeze of dissolution. He groped sideways for the hard bench and toppled back on to it. Then he raised his hands to his face and lost himself in the messiest and snottiest tears he had ever shed — within a moment they were everywhere, in his mouth, up his nose, in his ears, dripping down his throat …

And he was no use at all in the delivery room. ‘Tell her to breathe!’ he kept trying to say as they forcefully steered him towards the door. ‘Make her breathe!’

‘ Desmond ,’ said his wife. ‘Go and lie down somewhere. And wait for us. Wait! … I can do it. I can do it all.’

Dawn woke him — no, not his wife. Eos — Eos woke him: daylight woke him. When he tried to lift his head he found that his cheek was gummed to the vinyl seatcover, and he freed it with a terrifying rasp. He raised his head and saw that he was in a broad passage where others, too, waited and dozed … It took a while, but he eventually worked it out: no disaster could befall him, he decided, as long as he stayed perfectly still. But when he saw Mrs Treacher in the distance walking busily in his direction, he felt his head jerk away before there was any danger of reading the expression on her face.

‘Desmond?’

He swallowed chinlessly and said, ‘She all right? Dawn all right?’

‘Oh yes.’

‘Baby all right?’

‘They’re both all right. And it’s a girl.’

Her last words bewildered him. It’s a girl : he couldn’t understand why anyone would think that this was something he needed or wanted to know. Not boy, not girl, not boy. Merely baby, baby, baby …

‘Baby all right?’

‘Well she’s little. But she’ll get bigger.’ Mrs Treacher greedily added, ‘Same as all the others. That’s what they do.’

He let himself be guided into a place called the Recovery Room, and moved down a production line of triumphant feminine flesh (white nightdresses, warm limbs, white sheets); and there was his wife, sitting up in bed with her back arched and vigorously brushing her hair.

‘Oh, my poor love,’ she said, and smiled with a hand raised to her mouth. ‘Whatever’s gone and happened to you?’

And again he was led, or was rolled (his feet felt like castors), to an inner sanctum, or laboratory, and he gazed down with horror at the thing-alive beneath its dome of deep glass (like an inverted fishbowl), pinkish, brownish, yellowish, its limbs waving as mindlessly as the limbs of a beetle flipped on to its back. Now Desmond again deliquesced. He kept saying something, and he didn’t know what it was he was saying, but he kept on saying it, as if convinced that no one could hear.

The morning air enveloped him in a rough caress. For a while he just hung there limply. And so, it seemed, he might have indefinitely remained — but some large and complicated insect came and joyfully menaced him, and after a series of gasps and whimpers he set off. It was half past nine. His mission was to go home and fetch Dawn’s things. Could he accomplish that at least? Bus, tube train. He would have to move among the strong of the city.

But before he tried anything like that he entered a tea shop on the main road and ordered mushrooms on toast. He imagined himself to be bottomlessly hungry; and yet the black fungi felt quite alien to his tongue … There was a discarded tabloid on the chair beside him. He picked it up and spread it out. As if over a great divide, as if through the lens of a heaven-scanning telescope, he read about his astronomical uncle in the Sunday Mirror .

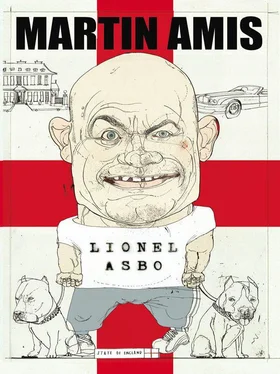

… All the blinds were drawn at ‘Wormwood Scrubs’, and the flag of St George was flying at half mast. ‘Threnody’, having miscarried, was under deep sedation. According to a statement issued by Megan Jones, the couple were completely devastated by this tragedy . And the security personnel at the house, together with other friends and advisers (Des read), had mounted a suicide watch on Lionel Asbo.

* * *

She was finishing lunch when he returned with a laundry bag containing her nighties, bathrobe, and sponge bag, together with several sinister (and tasteless) items like her nursing pads and nipple cream …

Dawn looked him up and down as he made for the bedside chair.

‘Don’t I get a kiss then?’ She patted her mouth with a tissue. ‘Cilla’s sleeping. Why not go and have a look at her? They’ll show you where.’

He said, ‘Cilla? Are we calling her Cilla?’

‘… I don’t understand you, Des Pepperdine. That was all you could say! Don’t you remember? Call her Cilla. Please call her Cilla. Call her Cilla, please call her Cilla . Don’t you remember? That was all you could say!’

He stared at his shoes. ‘Cilla. Cilla Dawn Pepperdine. Nothing wrong with that.’

‘Nothing wrong with that. Go on then. Go and have a look at her.’

‘I’ll wait for you. Eat your afters.’

She said, ‘Des, don’t worry. You’ll come to love her. I know you. You’ll learn … D’you think,’ she said, reaching for her apple pie, ‘d’you think he’ll see me now?’

‘Who? Oh. Him.’

And he slowly thought: Father Horace, Uncle Lionel, Grandmother Grace — these were the congenital attachments. You grew up into them, and didn’t have to learn how to do it, didn’t have to learn how to love. He said,

‘Take your time, Dawnie. I’ll wait.’

IN PHILOPROGENITIVE DISTON the ice-cream vans (with their sliding service panels and their voluptuous illustrations of tubs and cones and multicoloured lollipops) played crackly recordings of standard nursery rhymes as they toured the summer streets. This motorised trade in frozen refreshments was known to be very lucrative, and was regularly and publicly and violently contested (with pool cues, golf clubs, and baseball bats). And yet the vans, additionally daubed though they were with trolls and dragons and goblins, looked and sounded arcadian: hear those streaming bell-like gradations — as the ice-cream vans came curling round corners and bobbled to a halt. This, for now, would be the music of their lives.

Dawn and Cilla spent six nights in the Centre — one night for every week of the baby’s prematurity.

‘She takes a little more milk in her coffee than you do, doesn’t she Des.’

‘… Hard to tell. She’s all yellow. Takes after your dad. Sorry.’

For a moment naked Cilla looked up blindly; then, once again, she drowsed.

‘Even her eyes are yellow. The white bits.’ Des peered at her. His gaze slid up from the swollen vulva and its vertical smile — to the head: a dunce’s cap of flesh and blood and bone. ‘Her head . Looks like a Ku Klux Klan.’

‘I told you. They suctioned her. The ventouse. You weren’t there, Des.’

‘And there’s about a million other things that might go wrong with her.’

‘… Have you been at the books again? Don’t. Des, you can’t do it all with your mind. Just feel your way towards her.’

‘I’m trying.’

‘Don’t try. Wait. She’ll be fine . Touch her. Go on. She won’t hurt you.’

Why did he sense this — that the baby had the power to hurt him? He reached down and ran his fingertips over the moist, adhesive surface …

Cilla was five pounds one.

‘Just wait,’ said Dawn.

* * *

So he waited.

On the third day they were moved upstairs to a cubicle or wardlet intended for just two birthing mothers, and the second bed was empty. So they had the place to themselves. Which seemed to multiply Desmond’s difficulties … Horace Sheringham, himself just out of hospital, naturally stayed away, but Prunella was of course a good deal around; and Uncle Paul came, and John came, and George came, and even Stuart came; and Great-Aunt Mercy came. No one noticed that Des was not what he appeared to be — was not the euphoric first-time father, speechless with pride. But then Lionel came.

Читать дальше