At five o’clock it came through on AP. A matter of hours after granting her first photo opportunity for two and a half months, and revealing her ‘bump’ in a ‘Self Esteem’ ensemble at ‘Wormwood Scrubs’, ‘Threnody’ had been helicoptered to a private clinic in Southend.

Meanwhile, at Avalon Tower, everything was as it should be. Everything was embarrassingly normal. Wise nature wisely steered her course; Baby (they called the creature Baby now, because names meant nothing to them) — Baby ably and promptly and almost contemptuously prevailed in every test, its heart throbbed, its limbs flailed; Mother remained watchful but confident, while Father presided over an epic calm. There they sat, with their paperbacks, in idling Saturday light. A month and a half to go. Baby was the background radiation — the surrounding static — of their lives.

Every few minutes one of them said something or other without looking up.

‘Maybe her tits exploded.’

‘Dawnie.’

‘Well they do explode … On aeroplanes. Maybe her arse exploded.’

‘Dawnie. But you couldn’t call that tragic , could you. Something like your arse exploding.’

‘Yeah. Your fake arse exploding.’

‘… Hear it on the news. ”Threnody” had barely completed her photo op when her fake arse tragically exploded …’

‘Mm. After the tragic explosion of her fake arse, “Threnody” was rushed to …’

‘Has Danube been rushed to hospital recently? … Thought she might be doing another Danube.’

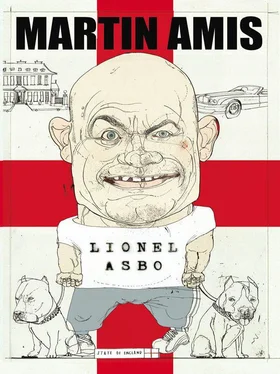

‘… Well Lionel doesn’t seem too bothered.’

‘Mm. To put it mildly.’

‘Maybe her bump’s fake too. Just a sandwich baggie full of silicone. Maybe her fake bump exploded … Oof .’

‘Not again? Not still?’

‘… Yeah,’ said Dawn tightly.

‘Have you been suffering in silence?’

Because — because there was this one little thing. Towards the end of her seventh month, Dawn started suffering from twinges in the base of her spine. They went to the Centre and consulted Mrs Treacher — and, anyway, it was all in the books. ‘ During the seventh month , Dawnie , the usually stable joints of the pelvis begin to loosen up to allow easier passage for the baby at delivery ,’ Des read out loud to her. ‘ This, along with your oversize abdomen, throws your body off balance . See? To compensate, you tend to bring your shoulders back and arch your neck . That’s you, that is, Dawnie. The result: a deeply curved lower back, strained muscles, and pain . See?’ And they followed instructions: straight-back chair, footrest, two-inch heels, nocturnal heatpad, and no leg-crossing. And at first all this seemed to work.

Des said, ‘Let’s go and look in at the Centre. See Mrs Treacher. Come on.’

‘No, Des. They’ll just say the same thing.’

Raising his book to chest height and gazing past it, he monitored his wife. Once a minute or so an alien presence would concentrate itself in the centre of her brow, and the blue eyes defiantly hardened. Then her chest rose and fell, and she sighed.

‘Okay, Dawnie, that’s it. It must be something like a trapped nerve. Come on. We’ll be there and back by seven.’

‘Leave me alone. I’m tired.’

‘Listen, I’d like nothing better than to do it all for you,’ he said. ‘But I can’t.’

‘Must I? All right. No rush.’

‘No rush.’

At six o’clock he called Goodcars.

An hour later they were still sitting side by side, in a strait-jacketed madness of traffic. Dawn was sighing, now, not in pain but in solemn exasperation. All four minicab windows were open to the shiftless air of early evening. Minicabs, minicabbing: the infinity of red lights … Raising his voice above the horns, the revved engines, the encaged CDs and radios, and the slammed doors (people were climbing out of their cars to stare indignantly into the overheated distance), Des passed the time in lively disparagement of Diston General — whose premises lay clustered to their left, like the low-rise terminals of an ancient airport.

‘It said in the Gazette they found pigeon feathers in the salad! In A & E on a Saturday night, it’s a five-hour wait. And if you’ve only got a machete in your head, they send you to the back of the queue! … We’re all right, Dawnie, where we are. We’re all right.’

‘I want to go home. It’s stopped hurting. I’m fine.’

Denied linear progress, the jammed metal, like a human crushcrowd (with all life hating all other life), now sought lateral motion, twisting into three-point turns and climbing the curb and the central divide; and Des felt so surfeited with his own strength that he wanted to step out into the road and call order — and then clear a path for them with his bare hands …

‘I was fine when we got in the car.’ And she dug her small head into his side. ‘Sitting here in all this has brought it back. I was fine.’

‘It’s a slipped disc, Dawnie. That’s all. Maybe Braxton Hicks. Or sciatica. They said you might need a bit of therapy. A few back rubs. That’s all.’

Far ahead there was a sudden easing. The column started to move, like a loose-coupled train slowly picking up speed.

He said authoritatively, ‘Baby can blink now. And she can dream. Just imagine. What can unborn babies dream of?’

‘Hush,’ she said. ‘Hush.’

Dawn found it quite difficult to straighten up as they climbed from the cab and entered the odourless whiteness of the Maternity Centre.

Mrs Treacher, paged by the front desk, immediately, voluminously, and all-solvingly appeared. And Des started thinking about the dinner he would eventually be having with Dawn in front of Match of the Day .

SHE LED THEM down a series of corridors and through a series of flabby fire doors with graph-lined portholes and past a series of water fountains of pearly enamelware. They reached a glass partition, and here Mrs Treacher turned and said with her ogreish smile,

‘I’ll just take a quick look at you, my love, while we park young Des in here.’

He was shown into a trim little office — evidently Mrs Treacher’s own, with its computer screen, its single shelf of textbooks, and the flat tins of paperclips and thumbtacks. Des noticed a small gilt-framed photograph (taken some time ago): Mrs Treacher, with husband, son, daughter, and a swaddled babe in arms. He found it strange to think that the midwife (always so hungrily available) had children of her own. But nearly everyone had children. It was normal: the most normal thing in the world.

So Des paced the floor, not with anxiety, not at all; he paced the floor with a sense of unbounded restlessness — he wanted tasks, challenges, tests of strength … The office window looked out on a lot-sized municipal garden, and after a while he rested his forearms flat on the ledge, and slowly surrendered himself to the dusk — the line of trees, the birdflight. With regret, he thought how little he knew about nature … The trees: were they, perhaps, ‘poplars’? The birds: were they, perhaps, ‘wrens’? Small, short-winged, proud-breasted, they climbed above the treeline in trembling, almost visibly pulsating surges, with such ardent, such ecstatic aspiration … That wren was a girl, Des decided, as he heard the sound of his own name.

Opening the door with a flourish he almost fell over a smocked patient in a wheelchair. It was Dawn — and Mrs Treacher was talking rapidly to a man dressed in green.

‘This is the waterfall,’ said Dawn. ‘It isn’t a trapped nerve, Des. It’s labour. The baby’s coming.’

‘Not possible,’ he said, raising his chin. ‘Not grown enough.’ He raised his chin yet further, and shrugged. ‘Not possible. Not prepared.’

Читать дальше