Anyway, I plopped myself down on a chaise longue in my parents’ yard, opened a beer, and began reading. I know a lot of readers, when praising a book, claim that it speaks to them. Those same readers might also claim that they saw themselves in the book. But those readers have nothing on me and A Fan’s Notes , which, the cover told me, was a “fictional memoir” about Frederick Exley, an overeducated and underemployed “youngish-old” man in Watertown, New York (a larger, colder, rougher military base town not even two hours north of my parents’ house), who basically plopped himself down on his mother’s davenport every day and read books and drank booze and went insane. There were some differences between us: Exley was obsessed with the New York Giants in general (and Frank Gifford in particular), whereas I was made loony by the Boston Red Sox (who in those days were the gold standard for long-term loserdom); and Exley had been institutionalized in insane asylums several times, while I hadn’t (and still haven’t, yet). Basically, Exley was a worse-off version of me (much worse, as it turned out: he’d died from his excesses a year earlier, although I didn’t know that yet). But Exley was also a great writer: sometimes he sounded like a guy who didn’t know he wasn’t on stage (“I saw myself a kind of Owl-Eyes come to Gatsby’s wake. sequestered from the one or two mourners, a curiosity weeping great, excited tears in the blue shade of funereal elms”), and sometimes he sounded like a guy who’d learned to talk in a bowling alley (“Wake up, yuh good-for-nothin’ bum!”), but no matter how he spoke, and no matter what he was speaking about, no matter whether he was self-pitying or self-deprecating, lyrical or profane, Exley was brilliant, and the proof of his brilliance was this book. He had made it, even though he was a loser, or maybe because he was a loser, or maybe the book itself was proof that he wasn’t a loser after all.

Reading the book had done strange things to me, obviously: I read it in one eight-hour sitting, and after I was done I felt much better, much less alone than I had when I started it. Although I felt more insane, too, more unhinged in a manic, jazzed up way. This is the book’s strange power: it makes you feel the terror Exley must have felt in the asylums, and it also makes you feel the hope Exley must have felt after being released from the asylums, the exhilaration he must have felt when this document of his insanity was finished and published, the fear he also must have felt in knowing that these highs were only temporary, the lows always right around the corner.

Anyway, just after I finished reading the book, I received a phone call from a friend, and in a rush, I told her about the book, what it was about, how I’d seen myself in it, how it had made me feel. After I was done talking, she said, “God, it sounds terrible.”

“What does?” I asked. “The book or the way it made me feel?”

“All of it,” she said.

“No, you don’t understand,” I said, but then I stopped. Because I could hear the nutty whine in my voice, and it reminded me of the way Exley’s voice sounded when he’d explained to his wife-to-be about his obsession with Frank Gifford, and how she said he must despise Gifford for being famous the way Exley never would be. Exley responded thusly: “‘Despise him,’ I said. I’m certain my voice reflected my great incredulity. ‘But you don’t understand at all. Not at all! He may be the only fame I ever have!’” And then I realized that as much as I loved A Fan’s Notes , I did not want to be the guy who wrote it. I did not even want to be the guy who was so obsessed with it. Which is why, years later, I made up someone who is even more obsessed than I was, and then put him in a book so I could talk about what it’s like to love things — a man, a town, a country, a book — that can be difficult to love. Do I hope you’ll love my book as much as I loved Exley’s? Do I hope you’ll read, or reread, Exley’s book and love it, too, after all these years? Do I hope that if Exley were alive, he’d love my book as much as I loved his? Hope, of course, is the lie you tell yourself to keep from going insane. But yes, that is what I hope.

1. Many novels feature what is known as an “unreliable narrator,” a narrator who may or may not be telling the reader the truth. To what degree do you believe Miller Le Ray to be unreliable? Is he unreliable just because kids with active imaginations are always unreliable, or are there other, more complicated, reasons behind his unreliability?

2. Does Miller seem like any nine-year-old boy you know? If so, or if not, is that a problem? Do we want children in books to be like children in life?

3. What does this book say about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and our reasons as a country and as individuals for fighting there?

4. What does this novel say about the power of a book like A Fan’s Notes , and the power of books in general? Would you want to be like Miller’s father — to feel so strongly about a book that you pattern your life after it? Is that kind of reaction a testimony to the weakness of the man or the power of the book? Is there some sort of ideal effect a book can have on us?

5. Talk about Miller’s mother. Would you make the same decisions she makes? Why does she make them? Do you blame her? Does Miller? Does Dr. Pahnee?

6. Speaking of Dr. Pahnee, discuss his transformation over the course of the novel. Does he become a better person/character? A more interesting one? Is there a difference? And do you consider him reliable or unreliable as a narrator? Why?

7. The relationship between Dr. Pahnee and Miller looks, superficially, like a classic teacher and student or father and son literary relationship, except that both these characters lie to each other and use each other. Does that mean they don’t really care about each other? How would you describe their relationship?

8. How do you interpret the end of Exley? What is it Miller is made to see?

9. Watertown, New York: Miller’s mother hates it; Miller and his father love it. How do you feel about it after reading this book? How do you think the author feels about it? Why do the characters who love it, love it? Are there places that, because they’re difficult to love, make you love them even more?

10. A Fan’s Notes is clearly important to this book, to its characters, and to its author. Does reading Exley make you want to read that book? Does Exley make Frederick Exley seem like a likable character/person/writer? And how would you define likable?

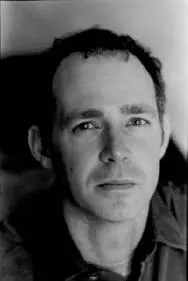

JON HUGHES/PHOTOPRESSE

Brock Clarkeis the author of An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England , which was a national bestseller and has appeared in a dozen foreign editions, and three other books. He lives in Portland, Maine, and teaches creative writing at Bowdoin College.