Those collected in the birthing room blinked as their pupils constricted with this explosion of photons. Everyone stared at the baby wriggling in the doctor’s outstretched hands. In the harsh light of the fluorescents, the infant’s skin, marked by the last globs of remaining vernix, was as black as the darkness from which he had just emerged. The umbilical cord and its apparatus dangled white and translucent against tiny, pumping legs the color of charcoal. Such monochromatic contrast appeared manufactured; the child looked like a puppet come to life.

“Why is he. . so like this?” Kermin finally blurted out.

“I wouldn’t worry,” Dr. Sherman said reflexively, finishing the handoff to the nurse. “Many newborns have a different skin color when they first come out of the womb. A mark of transition. This will all correct itself.”

“Is something wrong?” Charlene asked, drunk on her drugs, her pasty skin flush with the exertion of her labor. She reached for her child, but he was already being wheeled out of the room on a special trolley, followed by the doctor, who began yelling at someone down the hall.

“Is something wrong?” Charlene asked again. “What is that smell?”

“He is. .” Kermin said, staring at the door, left to wander closed on its hinges. They were suddenly, strangely alone. “He is. . Radar.”

“Radar?”

“His name: Radar.”

To her horror, Charlene realized they had never settled on a name. On several occasions they had tentatively circled the topic, but each time, all she could muster was a halfhearted short list of names for girls, and these tended to be lifted directly from famous novels: Anna, Dolores, Hester, Lucie, Edna. Every choice seemed either too obvious or too obscure or both too obvious and too obscure at the same time. How to name someone who existed only in theory? And coming up with a single viable boy name proved next to impossible. You were not just naming the boy— you were naming the man . Kermin, of course, proved no help at all; all five of his suggestions had been lifted from an electromagnetic textbook. And so Charlene succumbed to the narrative that they would have a girl and that all would become clear later. The decision of the name had been abandoned for simpler, tactile assignments, such as assembling the crib. They had cleared out space for the nursery; they had bought diapers and a kaleidoscope of onesies; they had inherited an outdated perambulator from her parents; but they had chosen no name. Except now that the baby had arrived (and left again), now that the baby had in fact revealed himself to be a he, the absence of a name suddenly took on great significance. He could not exist without a name.

“Radar,” Kermin said again. “You know, radar . Like bats. And aeroplanes.”

“I know what radar is,” she said. She willed her brain into action. “What about. . Charles?” Charles had been the name of her preschool boyfriend. He had punched her in the stomach to declare his love. She had not thought of him in at least thirty years, but now his name rose from the depths and became the stand-in for all things male.

“Charles?” said Kermin.

“Yes, he can be a Charlie. . or Chuck. . or Chaz.”

“Chaz? What is Chaz?”

She sighed. She was too tired for this.

“Okay, not Charles, then. What about your father’s name?”

“Dobroslav? This is peasant name.”

“I’m being serious, Kerm! What about your name?”

His own name was not so much a name as a signal of protest. In the small Serbian village in eastern Croatia where he was born, a name was practically all you had. To know your name was to know your history, your present standing, the circumscription of your future. It was the one thing you could never escape. His father, in a feat of madness or brilliance, had bucked their heritage and invented the name Kermin, in service to no tradition, lineage, or culture. Kermin had thus been both blessed and cursed: his singularity established, he could claim to have never met another with his same name, but he had also weathered a lifetime of confused looks when introduced on both sides of the Atlantic. Kermit? Like the frog?

“But listen,” he said. “ I am being serious: Radar is name. Have you seen this television program M*A*S*H ?” He articulated each letter, as if they were made out of wood. “Corporal Radar O’Reilly can sense the choppers before they arrive. It is like he has this ESP.”

“We don’t want our child to have ESP,” said Charlene, bringing her hands to her face. The hospital bracelet white against her wrist. “I just want to see him. . Where did they take him? They can’t just take him like that. . I want to see him, Kerm. Bring him back to me.”

Later, hunkered down in a deserted corner of the hospital, Kermin tapped out a message on his telegraph key, his thumb conjuring signal with the quiver of the smooth brass lever. The clusters of clicks and clats evaporated into the air, invisible pulses slipping out into the Jersey night, to be collected like dew by the radios of those who were listening in the early-morning hours:

— —•• — •—4 17 75.

MY SON IS BORN. RADAR RADMANOVIC.

MOTHER IS FINE. BABY IS FINE. I AM FINE.

KAKAV OTAC TAKAV SIN.

73, K2W9

Moments before, the nurse had asked Kermin for the child’s name.

“I must type it up,” she said. “For the certificate.”

He had glanced through the doorway at his sleeping wife.

“Radar,” he said, testing the boundaries of truth. “It’s Radar.”

“Radar?” The nurse raised her eyebrows, unsure she had heard the word correctly.

“Radar,” he confirmed, bouncing and recalling his fingers from an invisible barrier. “Like this: Signal. Echo. Return .”

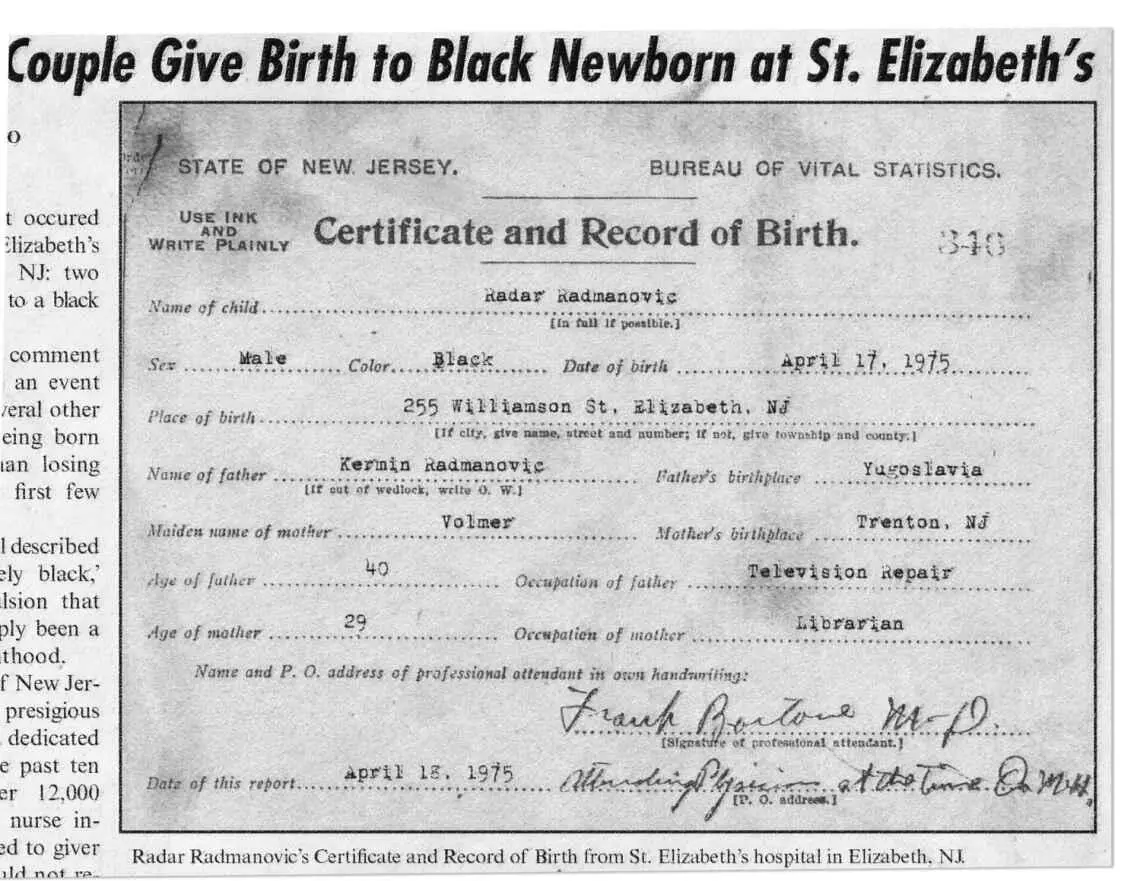

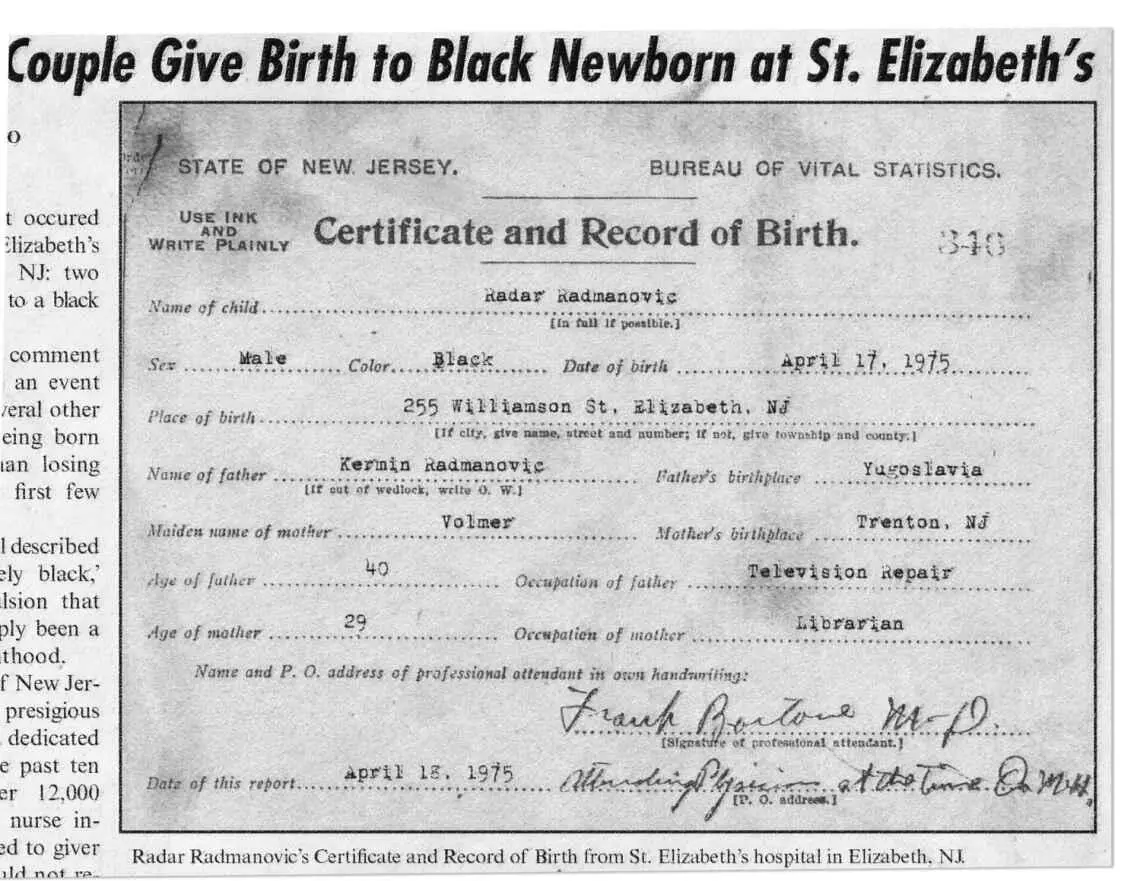

Fig. 1.1. Radar’s Certificate and Record of Birth

From Popper, N. (1975), “Caucasian Couple Give Birth to Black Newborn at St. Elizabeth’s,” Newark Star-Ledger, April 18, 1975, p. A1

The birth of such an extremely dark baby (described as “blacker than the blackest black” by an overeager Star-Ledger reporter) to two white parents was Jersey gossip that could not be kept quiet for long. The news of the birth must have been leaked by one of the orderlies, or one of the janitors, or perhaps even the nurse who had typed up the certificate of birth. Someone had talked to someone who had talked to someone, and suddenly there was a small group of reporters wandering around the maternity ward the next morning asking questions to anyone who would listen: You’re telling me this wasn’t just a mix-up, right? The kid could be from another family. . No? Okay, well, had the mother slept around? All right, all right. Fair enough. So then what was wrong with him? Okay, but what do you call that kind of thing? Was it a disease? What were the chances of this kind of thing happening? Yeah, but ballpark: one in a million? One in a billion ? How black was he really ? That black? Like Nigerian black? So then, when can we see him? What do you mean? Well, come on now, that’s a load of horseshit.

The day after his birth, the Newark Star-Ledger ran a front-page article with the relatively modest headline “Caucasian Couple Give Birth to Black Newborn at St. Elizabeth’s.” Lacking a serviceable photograph, they settled for a poorly rendered xerox of Radar’s birth certificate, as if this was all the proof anyone could need. Across the Hudson, the New York Post declared, “Jersey Freak of Nature: White Parents. . Black Baby!” and then proceeded to give very few details elaborating on their inflammatory headline. Baby Radar, caught in a genealogical conundrum not of his choosing, had suddenly become a cultural touchstone.

Читать дальше