“You cannot fix him,” Kermin said out of the blue one night as they sat watching a fuzzy episode of Three’s Company on the refurbished Zenith television. “He is not broken.”

She was so startled by this declaration that she didn’t say anything at first.

“You know that’s not what I’m trying to do,” she said finally.

“I don’t know what you are trying to do,” he said.

“Kerm,” she said as he got up and began adjusting the aerials.

“Kerm,” she said. “You have no idea what it’s like.”

On the television screen, John Ritter dissolved into static and then became whole again. Kermin moved the antennae about like a conductor, quietly swearing to himself, but after a while it was no longer clear whether he was trying to clear up the picture or make it worse.

• • •

ONE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, Charlene unlocked their mailbox as usual and nearly cried out. Inside was the beckoning glint of plastic wrap.

“Hey Kermin!” she yelled. She reached for it slowly, her hand trembling. A diagram of a hair follicle graced its cover. She felt herself recoil. Her son’s condition was not worthy of the lead article? A finger loosened the plastic seam on one side. She inhaled its pages, again searching for his elusive aftershave, but all she smelled was the buttery, slightly sterile aroma of processed paper and glue.

“Kermin!” she called up the hallway. “It’s here!”

She was searching the table of contents for the doctor’s name, the electricity flaring out into her fingertips. His name, his name — she wanted to touch his name. And there it was: page 349.

Kermin came down with Radar in his arms. He took a seat on the bottom step.

She read. Neighbors came and went around them. When she was done, she looked up, bewildered.

“So?” said Kermin. “What does it say?”

“I don’t know,” she said. The article was short. Barely three pages. She had expected it to be longer. She thought real science would demand pages and pages. Not this.

Radar was singing to himself, “Den we all say goodnight bunnee. Den we all say goodnight, goodnight, goodnight.”

Kermin rubbed his son’s head.

She sat down beside them and read it again. This time, she even read the figures and the footnotes. Radar grew bored and began walking up and down the stairs, counting each railing as he went. Kermin leaned over and looked briefly at the page, then shook his head.

“What does it say?”

“I don’t know,” she said, exasperated. “I’m not sure it says anything.”

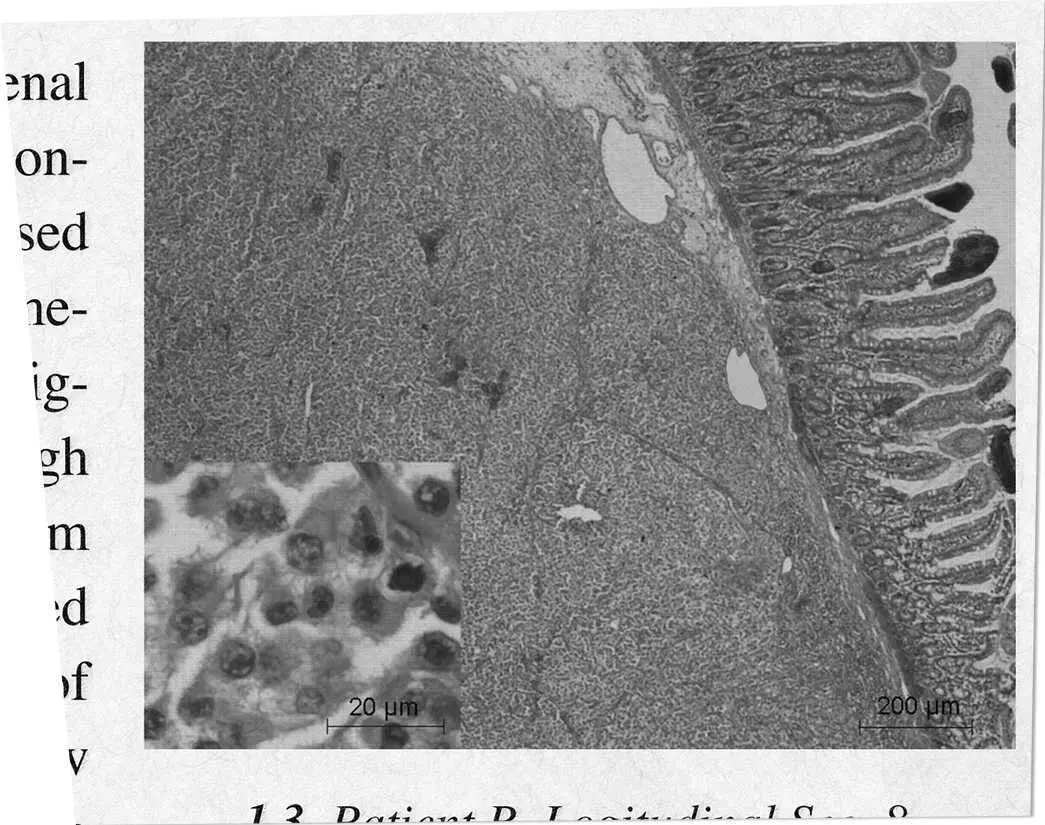

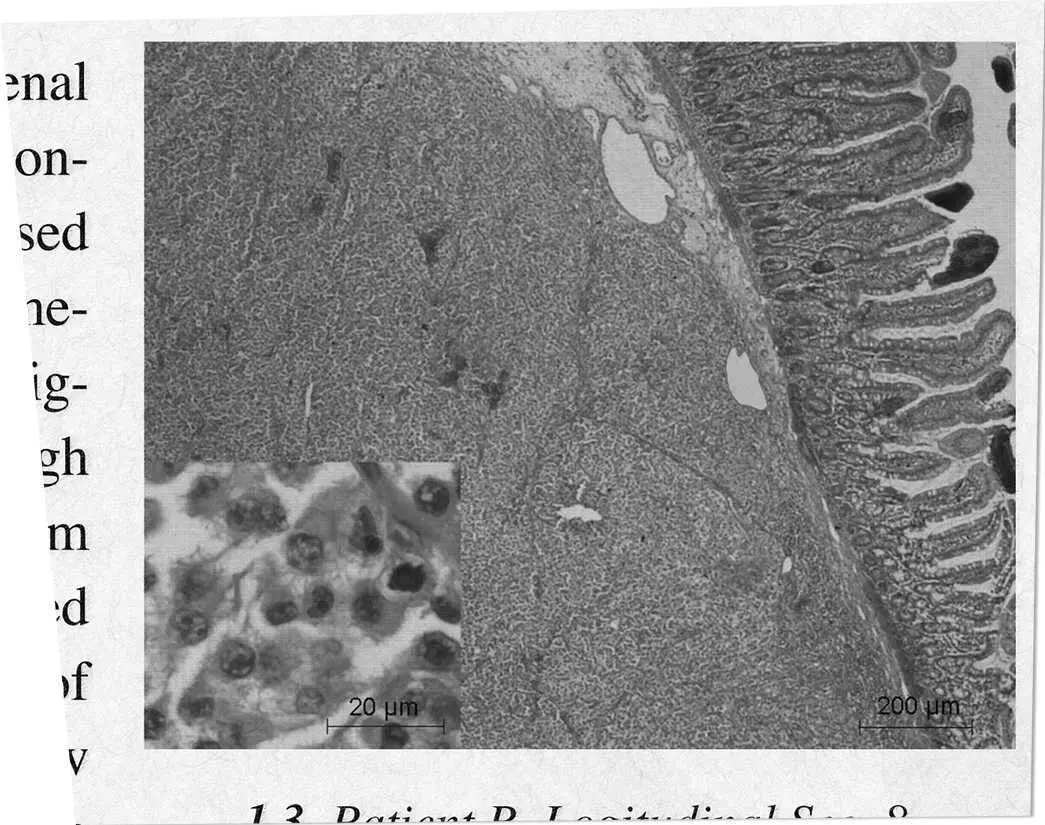

Indeed, as far as she could tell, “On an Isolated Incidence of Non-Addison’s Hypoadrenal Uniform Hyperpigmentation in a Caucasian Male” was nothing more than a professional shrug of the shoulders. “The unusual uniform darkening in this individual can be linked to a marked increase in melanocyte-stimulating and adrenocorticotropic hormones, though all other pituitary and adrenal gland functions appear normal,” Dr. Fitzgerald wrote in his conclusion, hiding behind the oddly disembodied language of the medical professional. “No doubt further genetic studies need to be performed to ascertain the precise catalyst for the over-production of these hormones, which are not present in either parent or gene group. In all other areas, however, the patient is a normal, functioning male infant. Chance transmutation, it seems, has struck again” (354).

Fig. 1.2. Patient R, Longitudinal Section 8

From Fitzgerald, T., “On an Isolated Incidence of Non- Addison’s Hypoadrenal Uniform Hyperpigmentation in a Caucasian Male,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 72: 351

“Chance transmutation?” said Charlene. She slowly collapsed onto the bottom step, let out a long, withering breath, and covered her face with her hands.

Radar came back down the stairs. “Why mommy sad?”

“I don’t know,” said Kermin.

“Someone mean her?”

“Come,” he said. He took his son by the hand and led him back upstairs.

• • •

THE NIGHT AFTER they received the article, Kermin, a man who did not drink but was clearly drunk, barged into their evening bubble bath, shortwave radio in hand.

“There is no more tests!” he said. “Jebeš ljekare!”

“Kerm, careful!”

He swayed. “ No more tests, do you hear me?”

“Okay, calm down. Don’t yell so loud.”

“And no more doctors!”

“ Okay .”

“Fuck this Fitzgerald so-and-so.”

“Kerm.”

“We know more than he does, and we know nothing! If he cannot find such-and-such, then there is nothing to find. Moj sin je zdrav .”

He reached into the bathtub to touch Radar’s head and tripped, dropping the radio into the sea of bubbles. The shortwave, chattering away, sputtered, slurped, and went silent. Charlene screamed, thinking they would both be electrocuted. She clutched their child to her chest. Radar, dark and radiant against his mother’s pale skin, began to whimper. Kermin grasped clumsily at his machine and promptly fell into the bath with them.

A shocked silence. And then Kermin started to laugh. After a moment, Charlene joined him. They laughed and built a tower of bubbles on Radar’s head, who waved at his crown. The air parted, the clouds receding. They did not have to fix this anymore.

It was a clean break, or as clean a break as you could hope for. In the months that followed, Charlene felt closer than she had ever felt to Kermin. They started sleeping together again for the first time in almost a year, though she still insisted on using at least two forms of birth control.

Perhaps sensing their daughter had turned over a new leaf, her parents offered to help them buy a house, an offer that Charlene begrudgingly accepted. They moved out of their apartment in Elizabeth and into a single-family faux colonial on a tight suburban street in Kearny, away from the Serbian community that had sustained and battered them. The sultry S-curve of the Passaic River formed the real and imagined border between their old lives and new.

Charlene brought all of her books with her — boxes and boxes of them. There was ample shelving in the new house, and she spread out her collection across several rooms, their spines clustered according to color. Visiting the new house, her mother said the library looked like a Rothko painting.

“It’s not a bad thing,” she said. “Just different.”

Soon after, Charlene hung white sheets in front of the shelves, as if to protect the books from an imminent construction project that never came. The sheets, once hung, were accepted and then forgotten, and would remain in place for the next thirty years. To fetch a book, you had to step through the curtain into another realm, into a mausoleum of forgotten bindings.

Kermin also moved his business across the Passaic, to a lonely little block in Harrison, next to a synagogue and a karate studio. Without the cultural patronage of the Serbs, he had trouble attracting new clients, and what little business which had sustained him in Elizabeth quickly dried up. Kermin sat in his new shop, surrounded by his electronic parts, and waited for the jingle of a bell that rarely came. He was perhaps the best TV-and-radio repairman in New Jersey, but he was not a people person, and the tiny television had not quite caught on in America in the way he had predicted. Americans liked big and bigger, and, most often, biggest. When things broke, they were more likely to buy a new one than fix what they already had.

Читать дальше