Otik’s motion sickness returned, and he began the now familiar routine of quietly puking into a bucket. Lars and Radar had grown so accustomed to this that they did not bat an eye, but Horeb grew concerned. He went over to the electric kettle and busied himself brewing some tea from several small bags of spices he produced from his knapsack.

“Here,” he said, presenting a mug to Otik. “For the stomach.”

Otik eyed the mixture skeptically but took the mug and gruffly mumbled a word of acknowledgment.

Horeb came over to Radar with a second mug of the tea.

“Thank you,” said Radar, accepting the offering.

“How do you feel, my friend?” said Horeb.

“I’ve been better. I’ve also been worse.” Radar sipped the tea. It was bitter and peppery, but it reminded him of Charlene and home. “What is this?”

“ Búku oela. A pan-African tea. I made it up myself. One could say it is post-traditional . Rooibos from South Africa, grains of paradise from Nigeria, calumba from Mozambique, ginger from Morocco. It heals the body and brings peace to the soul.”

Radar wished he could hear his mother give her olfactory report on the tea. He wondered if she would be able to smell all those countries.

“How did you learn to make it?”

“If I’m being honest with you. . the Internet,” he said, smiling. “The Internet will save Africa.”

Horeb glanced over in Lars’s direction. He leaned in close.

“I’m very honored to be part of your team,” he said quietly. “But I’m not really sure I understand what your team does. Can you explain this to me, please?”

Radar was baffled about why Lars had nominated him to be purveyor of information, particularly because he was the newest member and least qualified to describe what the group did. He barely understood it himself.

“I can try. But I can’t promise it will make sense,” he said, sitting up. He took another sip of the tea. He already felt better. The post-traditionalism was working.

As soon as Radar started talking, however, he found he had a lot to say. Much more than he thought he knew. At first he was worried that the history he was relating was not quite right — that he was leaving out critical details or shifting dates or mispronouncing names. He kept waiting for Lars or Otik to intervene and take over the role of storyteller. When they did not, he began to gain confidence, and there came a point at which he was no longer worried about whether he was getting it right or not. The story had become his. The story had become more than itself.

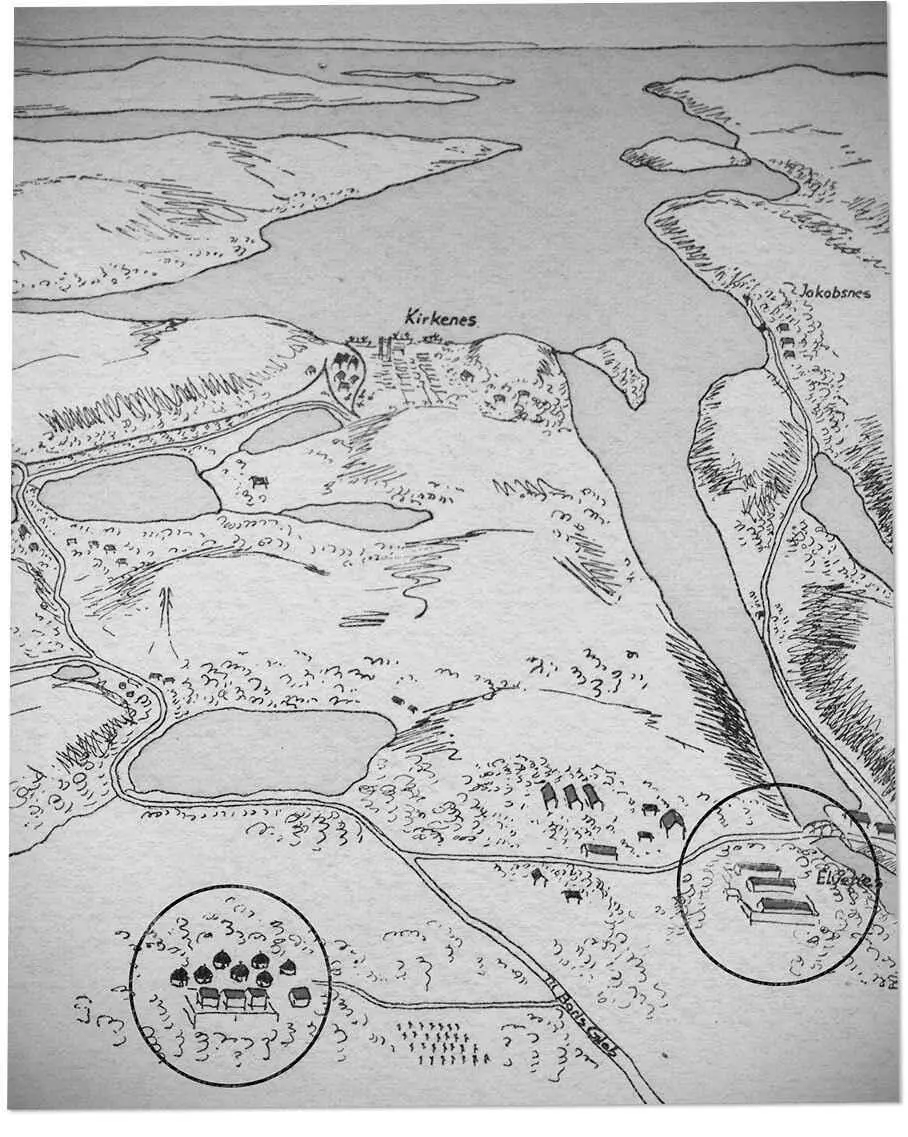

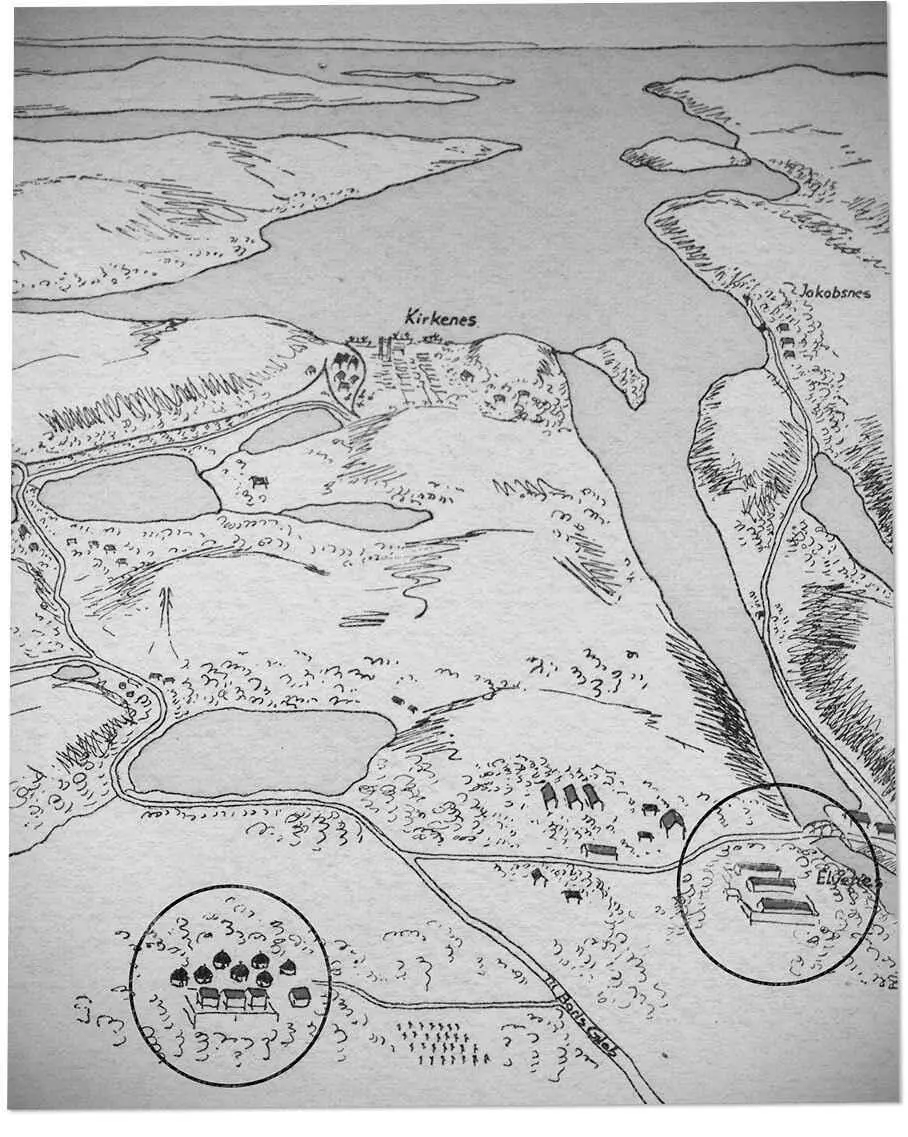

Fig. 5.5. Selected diagrams (1–5)

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler

Using the book his mother had given him as a springboard, he pointed to the diagrams as he told Horeb the history of the group, beginning with the labor camp for teachers in Kirkenes during World War II. The pictures, in their realness, in their little bordered truth, gave him courage.

“They were kept in two camps,” he said, pointing at the map of Kirkenes. “Here and here. This was where the idea for the group formed, in the breaks between heavy labor. The science teachers got together and began talking about science, and war, and theater, and they found they had a lot in common. When they were not working, there was nothing to do but talk. And out on the edge of the world like that, ideas can become big things. Ideas can become bigger than reality. And that’s why they went through with it. It was also desperately cold that winter. You can see the average temperature was minus twenty. The mind slows to a crawl when it’s that cold outside. But they knew it would one day be spring again. That one day the war must end.”

He waited for Lars to tell him he was full of crap. That he was making all of this up. But Lars stayed quiet, and so he went on. He described the creation of the Bjørnens Hule in the middle of the wilderness, pointed to the map of grass-roofed huts revolving around the Wardenclyffe tower.

“Do you know what a Wardenclyffe tower is?” Radar asked.

Horeb shook his head.

“Nikola Tesla invented it. He was a Serb. . one of my people. My father used to go on and on about him. Tesla came up with an idea that all electricity could be free. .” And so on. He talked about the experiments with electricity and nuclear physics, the preparations for the elusive performance on Poselok Island that was only discovered by two Russian fishermen many years later. He described the look of amazement on the fishermen’s faces. He recounted the Gåselandet show, destroyed by the massive Tsar Bomba, and the mysterious films of the exploding theater wagon that surfaced and were played at various underground parties to psychedelic soundtracks. He described the films even though he had never seen the films, even though he had seen only a series of stills in the book. But maybe this was enough. Maybe telling a story of the event was more powerful than witnessing it yourself.

“This was their theater wagon,” he said. He talked about the symbolism of the wagon at length, what it represented, its history in Europe first as a religious beacon, then as a satellite of safety against the state, then as a vessel of narrative transmigration. He did not know he knew all of this. He did not know he knew the term “narrative transmigration,” but out it came with all the rest.

Horeb didn’t ask a single question. He kept nodding and saying, “Yes, I see. Yes, I see,” though Radar didn’t know if, in fact, he actually did see or whether he was just playing along. When Radar got to the performance in Cambodia, he paused and looked over at Lars. But Lars was deeply ensconced in his work with the puppets. If he was listening in, he did not show it. So Radar narrated the tragedy of that night in Anlong Veng as if he had been there himself. He described Siri, Lars’s mother, the beauty of a woman who was so gifted and so strong, surrounded by all these men. She was a mother, a craftswoman, a visionary, a beacon of optimism in even the darkest of times. He began to feel his eyes growing misty. He described the sight of the wagon burning, the feeling of watching all that work go up in smoke. He pointed to the map of the killings. The sound of gunshots. Siri on the ground, looking at her husband, their hands reaching out to touch fleetingly before the life left them both.

Radar paused. “I’m sorry,” he said. He took a deep breath and pointed to the line on the map representing Lars’s escape with Raksmey to the Thai border.

“When they were within a hundred meters of the Thai border crossing, Raksmey stepped on a land mine,” he said. “His left leg was torn apart by the explosion. Part of his face was sheared right off. They heard shots behind them, and so he waved for Lars to go on and leave him. Lars tried to drag Raksmey. . but finally gave up. Those last thirty feet he had to walk on his own.”

There was a silence. Radar thought maybe he had gone too far.

Читать дальше