He was roused from his reverie by the click as the machine switched itself off. He wound the tape back again to find Van Mey’s voice, slimy-sounding and decayed after spending so long in the earth. It must have been after midnight now — according to later evidence, the same time as that at which, in a cold room a few hundred yards away, the medium, trying in vain to bring the voice of the dead man back to his two friends, gasped out, “I can’t, he doesn’t want to come — something’s preventing him…” Skinder Bermema stared at the last few lines as if he’d have liked them to go on of their own accord, It seemed to him this last part was written rather carelessly and didn’t fully exploit the possibilities of the subject.

It took him some time to remember what had happened next in that town in central China.

After he’d heard the evidence, Tchan had no difficulty finding out about the séances and the names of the people who’d attended them. Nothing was known about their arrest, but it probably took place without delay. It wasn’t certain whether Tchan had had them nabbed without more ado, or if he’d waited to catch them in the act during a séance. If the latter, he probably did make the macabre speech often attributed to him: after the door was smashed in and the conspirators were captured as they sat around the candles waiting in vain to communicate with the dead, Tchan is supposed to have said mockingly, “Were you waiting for his voice?” Then he burst out laughing. “Well, I’m afraid he’s stood you up, gentlemen! I’ve got both his voice and his soul — in here!” And he showed them the little bugging device.

It was the Albanian ambassador in Peking, an old acquaintance of his, who first told Skënder about the dreaded Zhongnanhai . And when he heard about the business of the microphones he was sure the General Bureau must have been mixed up in it. The same day he asked an embassy official who spoke the language what the ultra-secret mini-mikes were called in Chinese. “Qietingqi” was the word, he was told — pronounced “tchietintchi”.

“Are you going to write something about it?” the ambassador asked Bermema when he spoke to him about the séance. “China is still haunted by ghosts and spirits, despite all the denunciations of the old days.”

Skënder sat down on the bed and. gazed at the white curtains as he revolved all these memories. Various other incidents were now coming back to him …He lay down …A lunch near Tirana with some friends, after a rehearsal of one of his plays, and the maunderings of someone at a nearby table who’d had too much to drink: “In the third millennium, Albania will become Christian again, and if you want to survive you’d better change your name from Skënder to Alexander”, Going into hospital a year ago, the syringe in the nurse’s hand, and his own sudden doubt about it — a doubt that was somehow like the confusion he’d recently felt going into the Hotel Helmhaes in Zurich, because in Albanian the word “helm” meant “fish” …The women he’d loved, a tune, a balcony overlooking the sea, manuscripts and more manuscripts…An ashtray in a café, full of cigarette stubs of which only one had lipstick on it, symbolizing the disproportion between the emotion felt by the unknown man and that felt by the unknown woman…

He thought he must have drowsed off for a moment. And it was in a state between sleeping and waking that he imagined Ana lying in her grave. Or rather not her but a gold necklace which he’d given her once, and of which he’d caught a sudden glimpse as they closed the coffin.

He moved his head on the pillow to drive away the thought. But on the other, cooler part of the pillow Lin Biao’s question, ‘“Where are we going?” , seemed to be waiting for him, together with Lin Biao’s plot to kill Mao — strangely like Mao’s plot to kill Lin Biao.

Bet Skënder had had enough of these ruminations. His thoughts turned to the children’s skis in the hall of the apartment at home, and how his wife did her hair, sitting at the dressing-table, and a letter from a woman reader who was a bit cracked…And, for some reason or other, a poem he’d written long ago:

Like a Jewess exchanging her old religion for a new one,

There was a sudden shower of hail

Every time winter taps on the windowpanes

You will be back, even if you’re not here.

Even if you were changed into music, or mourning, or a cross

I would recognize you and fly to you.

And like someone extracting a pearl from its shell,

I would pluck you from music, the cross or death,

Alexander Bermema, he said to himself, trying out the new name the man in the restaurant had suggested. And again there went through his mind, like beads on a string, the coming of the third millennium, the ringing of bells, Ana’s tears, and the Place Vendôme in Paris on an afternoon so cold it intensified the shiver the prices of the diamonds in the shop-windows sent down his spine…

That was how Skënder spent the rest of the morning, sometimes lying down and sometimes pacing back and forth in his room. Every time he thought of his dead novel his hand went instinctively to his ribs, for it seemed to him something had been removed from his side.

At midday C–V— came and knocked at the door to tell him it was time for lunch. They went down together to the almost empty dining room, and hardly spoke to one another at all throughout the meal.

Back in his room, Skënder felt this Sunday would never end. For want of anything better to do he rang the bell, and when the Chinese floor waiter pet his head round the door he ordered a beer.

At three in the afternoon there was another knock, and this time it wasn’t C–V—. But before Skënder identified his visitor he noticed he was holding out a card with red ideograms inscribed on it: clearly an invitation, Skënder wasn’t sure whether it was by chance that he’d concentrated exclusively on the card, or if the messenger had trained himself to disappear as if by magic behind the proffered invitation.

As Skënder held out his hand for it he raised his eyebrows inquiringly.

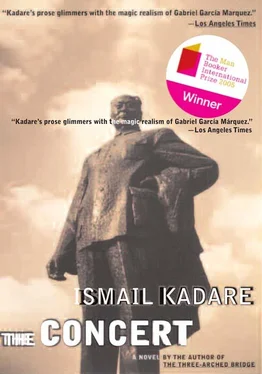

“A concert,’ the man told him, smiling.

Skënder scrutinized the card. The Chinese characters made no sense to him, but he managed to pick out the figures 19,30, which was presumably the time the concert started.

Well, a concert would be a welcome distraction amid this sea of boredom. It wasn’t four o’clock yet, but he was so glad to have something to do he opened the wardrobe and started looking for a suitable shirt.

IN ANOTHER HOUR (by which time Skënder Bermema had shaved again and chosen a shirt and tie, while in a nearby room C–V—, with whom he hadn’t been in touch, had done the same), all eleven hundred invitations to the official concert had been delivered to various addresses in Peking, and most of the recipients were in their rooms getting ready for the evening.

Some of them — mostly women — were still lying luxuriously in the bath, the shapes of their bodies blurred by the warm water, while in the distance their husbands were on the phone, asking other diplomats what they knew about this impromptu concert to which everyone was invited at scarcely three hours’ notice. Was it just the way the Chinese did these things, or did it have some special significance? It was very odd…Was it a concert being brought forward from a later date, and if so why? It had been rumoured for some time that Mao was ill…Or was it Zhou Enlai? Who could say? Anyhow, the concert was not to be missed. It would provide all kinds of hints as to what was going on: what you had to watch out for was the order in which the Chinese leaders arrived, who was seated with whom in the boxes, whether Jiang Qing was there or not…

Читать дальше