Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

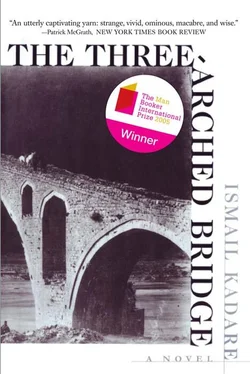

- Название:Three Arched Bridge

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Arched Bridge: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Three Arched Bridge»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Three Arched Bridge — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Three Arched Bridge», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The man finally succeeded in standing up, and after bidding the count farewell, the delegation left one by one. I left too.

It was bad weather outside. The north wind froze my ears. As I walked, I could not stop thinking of what they had talked about with the count. Something ominous had been discussed in a mysterious way. Everything had been carefully shrouded. I had once seen the body of a murdered man on the main road, two hundred paces from the Inn of the Two Roberts. They had wrapped him in a cloth and left him there by the road. Nobody dared to lift the cloth to see the wounds. They must have been terrible.

The thought that I had involuntarily taken part in a conspiracy to murder disturbed my sleep all night. My head was heavy next morning. Outside, everything was dismal Old, iron-heavy rain fell. Oh God, I said to myself, what is the matter with me? And a wild desire seized me to weep, to weep heavy, useless tears, like this rain.

29

THE RAIN CONTINUED ALL THAT WEEK, as drearily as on that day of the discussion. People say that rain like this falls once in four years. The heavens seemed to be emptying the whole of their antiquity on the earth.

In spite of the bad weather, work on the bridge did not pause for a single day. Builders stopped abandoning the site. Work on the second and third arches proceeded at speed. Sometimes the mortar froze in the cold, and they were obliged to mix it with hot water. Sometimes they threw salt in the water.

The Ujana e Keqe swelled further and grew choppier, but did not mount another assault on the bridge. It flowed indifferently past it, as if nothing had happened, and indeed, to a foreign eye there was nothing but an ordinary bridge and river, like dozens of others that had long ago set aside the initial quarrels of living together and were now in agreement on everything. However, if you looked carefully, you would see that the Ujana e Keqe did not reflect the bridge. Or, if its furrows cleared and smoothed somewhat^ it only gave a troubled reflection almost as if what loomed above it were not a stone bridge but the fantasy or labor of an unquiet spirit.

Everyone was waiting to see what the spirits of the waters would do next. Water never forgets’ old people said. Earth is more generous and forgets more quickly, but water never.

They said that the bridge was carefully guarded at night. The guards could not be seen anywhere, but no doubt they watched secretly among the timbers.

30

AS SOON AS IT HAD PUT ITS AFFAIRS IN ORDER, the deputation departed^ leaving only one man behind. This was the quietest among them’ a listless man with watery, colorless eyes. He kept to himself, as if not wanting to interfere in anyone’s business, and he often walked quite alone by the riverbank. Mad Gjelosh — who knows why — imagined that he had a special right to threaten and insult this man whenever he saw him. The flaccid character noticed the idiot’s wild behavior with surprise, and did his best to keep out of his way.

One day 1 happened to meet him face to face; he spoke to me first, apparently remembering me from the discussion with the count. We strolled a while together. He said that he was a collector of folktales and customs. I wanted to ask what this had to do with the bridge builders but suddenly changed my mind. Perhaps it was those watery eyes that made me think better of it.

A few days later he came to the presbytery, and we talked for a considerable length of time about Balkan tales and legends, some of which he knew, The tranquil water of his gaze became suddenly troubled whenever 1 mentioned them, despite his attempts to control his somnolent eyes.

“Ever since I have got to know them, 1 can’t stop talking about them,” he continued, as if trying to apologize.

I recollected in a flash the delegation’s interest in legends, and also how our count had mentioned them during the discussion. Now I no longer had any doubt that 1 was really talking to a collector of legends. Nevertheless, deep down inside myself, something thudded, calling for my attention, It was a summons or a vision that fought to reach my brain but could not, 1 do not know what kind of fog prevented it,

“I hope I am not irritating you by saying the same things over and over again,” he continued,

“On the contrary, ” I said. “It is a pleasure for me, Like most of the monks in these parts, I myself take an interest in these things.”

As we walked along the sandbank, 1 explained to him that the legends and ballads of these parts mainly dealt with what had most distressed people throughout the ages, the division of mankind into the two great tribes of the living and the dead, The maps and flags of the world bear witness to dozens of states, kingdoms, languages, and peoples, but in fact there are only two peoples, who live in two kingdoms: this world, and the next, In contrast to the petty kingdoms and statelets of our world, these great kingdoms have never touched each other, and this lack of touch has pained most of all the people on this side, No testimony, no message, has so far ever come from the other side, The people on this side, unable to endure this rift, this absence of a crossing, have woven ballads against the barrier, imagining its destruction. Thus these ballads mention those in the next world, in other words the dead, crossing to this side temporarily with the permission of their kingdom, for a short time, usually for one day, to redeem a pledge they have left behind or to keep a promise they have made.

“Ah, I see,” he said now and then, while his eyes stared as if begging me to continue.

I said that this is at least how we think on this side. In other words, we are sure that they make efforts to reach us, but that is only our own point of view. Perhaps they think differently, and if they heard our ballads they would split their sides laughing …

“Ah, you think that they probably do not want to come to us?”

“Nobody can know what they think,” I replied. “Besides Him above,”

A few black birds, those that they call winter sparrows, flew above us. He asked whether all the ballads sung were old, and I explained that sometimes new ones were devised — or rather, that is what people thought, whereas in fact all they did was revive forgotten ones.

I told him that an incident in the neighboring county ninety years ago, at the time of the first plague, had become the occasion for a new legend, A bride who had married into a distant house returned to her native land and, unable to explain her journey, declared that her dead brother had brought her home …

“Ah, it seems to me that I have heard it,” he interrupted me. “A bride called Jorundina, if I am not mistaken.”

“Jorundina or Doruntina. We pronounce it both ways,”

“It is a heavenly ballad. Especially the suspicions against the young bride and her defense based on the promise her brother had made to her while he was’ alive…. There is a special word in your language …”

“Besa,” I said.

“Baesa,” he repeated with a grimace, as if he could not get his tongue around the word and could barely extract it from his mouth,

“For years on end there were investigations to shed light on the secret. All kinds of suspicions were raised, and all kinds of explanations were given, but later all these were forgotten and it remained a legend.”

“Thank God,” he said. “It would be a sin to lose such a pearl.”

My pleasure that he appreciated the legend so much led me to say things that I would otherwise have avoided. I said, for instance, that whereas the Orthodox Church had several times tried to prohibit it, the ballad was now sung everywhere at Easter celebrations, and not only at feasts in Arberia, but throughout all the territories of the Balkans.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Three Arched Bridge» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.