BEN: I probably should switch over to coffee. But yeah, hell, give me a little more. You know, you’re mellower now, I think. Or am I imagining things? You don’t have that squinty look. Where’s the gun?

JAY: Mmm? Oh, it’s available. And I know a way in through the fence. One of the corners.

BEN: You won’t get fifteen yards, man. You might as well give me the gun and let me shoot you right now. Save yourself a walk.

JAY: I think I’ve got a fifty-fifty chance.

BEN: What can I say that’ll make you stop? Whistle the theme to the Andy Griffith Show ?

JAY: Not now, please.

BEN: What if I threw this glass at your head? Would that be a good idea?

JAY: No.

BEN: Then, when you ducked, I’d knock you down with the chair, maybe.

JAY: Don’t do anything like that. I’m jumpy enough as it is.

BEN: Here’s an idea. Just a suggestion, okay?

JAY: Okay.

BEN: And, you know, you can take this for what it’s worth because it’s not like my life is some shining example of how to live a life.

JAY: I know that.

BEN: But my suggestion is, get yourself a camera.

JAY: That’s your suggestion? Get myself a camera. Sure thing. Take some pictures of our nation’s capital, great. Heh heh heh.

BEN: No, I mean it, it’s been an enormous help to me.

JAY: It’s just that there’s no time now. The marination — it’s complete. This is the day.

BEN: I know what I’ll do, I’ll give you my — well, I’ll loan you my camera. How about that?

JAY: Thanks, but I don’t need to take pictures.

BEN: You don’t have to take any pictures. Honestly, you’ll enjoy just loading the film. The rolls of film are exactly the same shape as they were back when George Eastman’s engineer first designed them a hundred years ago. Back then they were called cartridges — they looked like shotgun cartridges. Now it’s called one-twenty film.

JAY: Is it expensive?

BEN: Yeah, it’s pretty expensive, but it’s worth it — the grain is so fine now. So when you can’t stop thinking about the war, about how evil George W. is, how corrupt Cheney is, all that — all of which is true — but when it’s paralyzing you, and you’re not doing anything but thinking about the horror and the gangrene, load some film and go outside. Is there a park near where you’re living?

JAY: There’s a little green spot, yeah.

BEN: Fine, so go there. You might see, oh, I don’t know, a nuthatch on a fence. You think, take the picture? No, no. There’s somebody’s cat, sniffing at a blade of grass. Take the picture? No, no. You move on. A twisted piece of wire on the ground. Yes? No, no. You see what’s happening?

JAY: I’m not sure I do.

BEN: What’s happening is that the weight of the camera in your hand — and remember, it’s a heavy camera — the holding of it is changing the way you look at everything. You look up at the buildings, the stonework up there — ah, and then you see the trees. You put your eye to the viewfinder, and you’re in the lens.

JAY: You’re in the lens?

BEN: Exactly, you’re in the lens. And then you focus. That’s the great moment, when you turn the barrel of the lens and all the little wisps of fog sharpen a little, sharpen some more, and become parts of a tree. All these branches branching off.

JAY: The trees really get to you, eh?

BEN: Especially the old twisted ones. The last couple of months I must have shot, oh, maybe a dozen different trees. It’s best to get to them before their leaves are out, so that you can see the whole structure.

JAY: I guess I’m out of luck, then.

BEN: No, no, leaves can be good, too. Leaves are good. Oh, but there was this one enormous catalpa tree a couple of miles from our house. It was kind of a wet, misty day, and I walked up to it, and I went “Whoa,” and I brought it into focus and the whole thing just came alive for me in the viewfinder. It was an incredible explosion of black twigs reaching in every direction. I was down to maybe a thirtieth of a second, and I squeezed the trigger—

JAY: The trigger?

BEN: I mean the shutter, the little button.

JAY: You’re as messed up as I am.

BEN: Anyway, I squeezed it, and the camera kind of shuddered. See, there’s a heavy mirror in there that has to flip out of the way, so it kicks a little when you take the picture. But very fast. Cloonk.

JAY: Heavy but fast.

BEN: Yep, and I knew I had that catalpa in the bag. I knew its secrets. Yet there it was still out on the street for everyone else to enjoy. So who cares then about George W.? He’s irrelevant. He’s irrelevant. You see?

JAY: It’s kind of funny — I hate to say it, but you know what all this makes me think of?

BEN: What?

JAY: The Sixth Floor Museum.

BEN: What’s that?

JAY: You don’t—? Oh, that’s the museum at the Texas School Book Depository, in Dallas.

BEN: You went there?

JAY: I did indeed. They have a row of cameras under glass there — all the cameras that people were using on the day of the assassination. The old home movie cameras, and a kind of Polaroid camera that took a picture of a blob that supposedly was a person in a bush on the Grassy Knoll, but it’s really a blob. In fact, it isn’t even a blob anymore, because the Polaroid has faded, so all they’ve got is this enhancement. But the row of cameras is great, it’s like a memorial. And you look at them for a little bit, and you nod, and then you walk over to the corner of the floor — the sixth floor — and you stand in the place where supposedly the guy aimed his rifle and shot the president.

BEN: I see.

JAY: They’ve got the boxes of schoolbooks piled up so that it looks pretty much the way it did. To me, frankly, it seemed like a very awkward vantage point. There were two guys there who were hunters, and one of them said, “Lord, that’s one tough shot.” They talked about how slow the car was moving, and the other guy said, “All I can say is, I sure couldn’t make that shot.” They were talking softly, you know, and for a moment we were all thinking like assassins.

BEN: Why did you go there?

JAY: It was last year, just around this time last year, I took the bus all the way from Birmingham to Dallas. There’s a great bus station in Dallas, it’s practically untouched, classic Deco lines, the Greyhound station. Just the way it would have looked, at least on the outside, in 1963.

BEN: But what made you take the bus there?

JAY: It was that thing I read on the Net, the news story. It was so awful.

BEN: About what?

JAY: It was in the Sydney Morning Herald .

BEN: Sydney, Australia?

JAY: Yes.

BEN: What was the story?

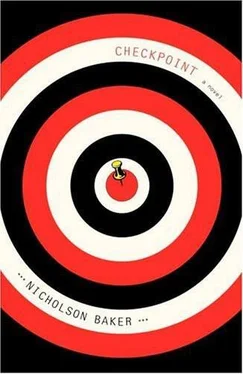

JAY: Oh, it was about this checkpoint, and, um. I don’t want to — oh, it was a thing that happened, that nobody would have ever wanted to happen. But it happened, and it made me so mad. So mad at him.

BEN: Why don’t you tell me.

JAY: It was just an event. Well. Okay. There were a bunch of Army guys there and this Land Rover drove toward them. It was filled with a family, they were fleeing. Many children. Everybody was jammed into this car, and they were trying to get out of the war zone.

BEN: Okay.

JAY: And they waved, and somebody at the checkpoint misinterpreted the wave, and so there was a huge blast of fire, and one of the women in the car, the mother, she said, “I saw the—” Sorry.

BEN: It’s okay.

JAY: She said, “I saw the heads—” Pull myself together.

BEN: It’s all right.

JAY: She said, “I saw the heads of my two little girls come off.” That’s what she fucking said. I’m not kidding you, man. “My two little girls.” That’s what she fucking said. Can you imagine it? You’re just trying to get your family out of a war zone? Your farm’s already been blasted by helicopters, and then a bunch of guys in Kevlar open fire on your kids, and you see that happen? Ho, God.

Читать дальше