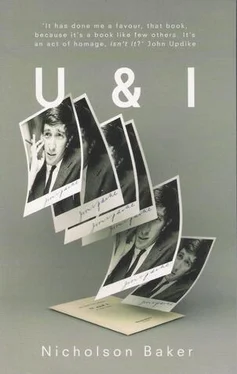

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It may seem incredible, given how little I had published and how bad it was, that I could have even idly theorized as to why Updike wasn’t making an effort to seek me out, but I did. I was puzzled as well by his need to golf with a writer. One of the things I had admired about him was his deliberate self-removal from New York, and his unwillingness to participate in writer’s conferences or accept academic appointments or get himself involved in that whole tragic, talent-draining process whereby writers cluster together to attract aspirants who pay big money in exchange for some chumminess and advice (meanly I call it tragic, when I had been very willing to write out a check for hundreds of dollars in order to gain the audience of Donald Barthelme, and I had had a wonderful time!): yet here Updike was seeking out another writer to play golf with. It was that frigging National Book Award, I thought: that was the ticket into his esteem. But this was ridiculous. There were many explanations, aside from Tim O’Brien’s simple likability. Updike was perhaps even then working on the essay about his pro-Vietnam-war activities, and he might well have been interested in getting to know somebody articulate who knew as much about Vietnam firsthand as O’Brien did. He could have already done the nonliterary golf-buddy thing and found that even with a strict prohibition against bookchat, even if they only talked about cars or the resale market for dredged golf balls or urban renewal programs, a writer was a more engaging companion to clump from hole to hole with than some division manager from Digital. Still, it was this anti-bookchat rule that especially focused my resentment. “Yup, we’re going to pretend we’re two regular guys,” is how I first interpreted it. Imagine having a rule of conversation. Jeezamarooni! If I were out there with Updike on the fairway right now, and he had laid down that rule, I would, between bogeys, be coming out with nervous snickering references to Richard Yates and Patrick Süskind and Julian Barnes, just to test his tolerance of me as a golf partner — just to see if he would make an exception for me.

And yet of course I saw why the prohibition was necessary. When you spend a fair amount of time writing about other people’s books, or making sure to steer clear in your own books of images or scenes that you remember from other people’s books, you naturally don’t want in your off hours to cover the same ground with all the diminishing slackness and imprecision of conversation. You’re trying to be as different as possible from everyone else, as Frost more or less said, and you don’t want any influences to travel back and forth in advance of the demonstrable influences you supply and receive in the public world of print. (Plus there must be a kind of small thrill in feeling the power in yourself to be able to set a rule of conversation: feeling the unsettling authority of saying, “But Tim, I do think we should follow one rule …”) If I were golfing with Updike this week, would I tell him, “Hey, I’m reading Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library , and you know, once you get used to the initially kind of disgusting level of homosexual sex, which quickly becomes really interesting as a kind of ethnography, you realize that this is really one of the best first novels to come along in years and years! The guy does everything — dialogue, scenic pageantry, wit, pathos, everything!” I would want to tell him this, but I wouldn’t, I don’t think, because what if by some chance Updike hadn’t read Hollinghurst yet, and what if my say-so, the last of many, was just enough to make his eye pause on this book in the Vintage catalog and order it, and what if he read it and its presence in his mind caused him to shift his writing ever so slightly in a particular direction either toward or away? Or, alternatively, what if Updike found me irritating enough as a person that my ravings about Hollinghurst dimmed his own previous excitement about the book? Would I want to have tampered casually with his literary development, his fate , in that way? And what if he mentioned that he’d been rereading Shaftsbury and liking him, or rereading Wallace Stevens and liking him less? For months afterward, this bit of inside information would be the first thing I would think of in connection with these artists: I would read them with a slightly different eye, and I might as a result write differently. So no talk about books. But it was much worse than that. Could John Updike and I talk about cars or self-doubts or the weather? About the psoriasis we have in common?

Say he and I were golfing, and I was getting the hang of it a little better, and the birds were supplying their own spatial illusions to the sound track, and I suddenly came out with “Wow, John— golf. Now I see why you like it so much. It’s an externalized battle with your skin. Your job as a golfer and as a psoriatic is to keep from drifting into the rough, right? You want to arrive as efficiently as possible at the finest, smoothest section of grass!” Say I said this fairly dumb thing to him one balmy afternoon. (Crossing my fingers, in doing so, in the hope that it wasn’t something he himself had written that I had forgotten.) And what if a few years later he has occasion to write another golf story — some masterfully pastoral Byezhin Meadowy kind of thing — and the golf-course/psoriasis parallel occurs to him then, and he drops it in in a perfect spot, without the exclamation point, improved almost beyond recognition. Will I be happy to read this? Maybe eventually, but it will take some adjustment. As I say, I’m a psoriatic myself, and though Updike has said lots of what can be said about the disability, there is more, and there might come a time when I would want to have a scaly-rinded character imagine himself or herself as smooth as a golf course. So no — I couldn’t talk about psoriasis with Updike: I’d be too scared of hearing something from him that I would itch to use before he’d used it, or of tempting him with a flake or two from my experience that I would want to keep for myself — or of hearing him say something similar to something I’d already noted down and was planning to use, and having my note killed by his passing mention. And I would sense his detection of all this ridiculous guardedness on my part: I would see him smiling to himself after I had begun to say something animated and then had halted abruptly and switched to a conventional formula because I had realized midway through that what I had been intending to say was possibly interesting enough for me to want to use somewhere, or because I wanted to hustle him into thinking I was denser and more conventional than I was, so that he would relax and talk more freely, and so that I could surprise him later, making him think to himself when he read some piece of mine, “Hm, I guess that Nick Baker is not to be underestimated.” Our very guardedness and mutual suspicion, or at least my suspicion (or hope, rather) that the suspicion was mutual, would be an undertone of the outing that both of us might have our eye secretly on, to see whether there was anything in it that had an unsaid quality that could be transported effectively into print. Perhaps I would come right out and allude to my awareness of his potential wariness of me, just to see what happened, and he would reply that if there is wariness it is a middle phase and passes, as does the more specific hate you can feel toward young bright unsaddened people running up and down the aluminum ladders of their own insides (in Forster’s phrase) with no storm windows yet to change, no duties or sins to bend their chirping ambition in interesting ways, and that in fact you begin to take a sort of nostalgic joy in seeing that unrefined unwise reputationless rawness start to sort itself out, and you begin to find some amusement in watching a young writer prepare himself to do the small bold thing in the elder writer’s presence, such as I had just done in alluding to his wariness, and that if I wrote with pretend farseeingness about my egotistical thought that he had a wistful wish to be me, he would counter by writing about his self-disgust at the pretense of generousness he’d shown in so breezily pretending that he didn’t care whether I appropriated the complexities of that afternoon game of golf or not, and about the feeling you can have of delegating a piece of experience to someone, happy in the knowledge that though the idea of a biography’s being produced about you is horrifying, the idea that someone is catching you in action from a perspective you’d never yourself have is pleasing. Quickly there would be a screech of feedback and the whole discussion would have to be cut short and I would be carted or caddied quickly off. Literary friendship is impossible, it seems; at least, it is impossible for me. Indeed, all male friendships outside of work sometimes seem to be impossible: you look at each other at the restaurant at some point in the conversation and you know that each of you is thinking, man, this is futile, why are we here, we’re wasting our time, we have nothing to say, we’re not involved in some project together that we can bitch about, we can’t flirt, we feel like dummies discussing movies or books, we aren’t in some moral bind with a woman that we need to confess, we’ve each said the other is a genius several times already, and the whole thing is depressing and the tone is false and we might as well go home to our wives and children and rent buddy movies like Midnight Run or Planes, Trains, and Automobiles or The Pope of Greenwich Village when we need a shot of the old camaraderie. (Updike catches some of the false jocularity of reunions in a story about two ex-Harvard Lampoon types in New York, one of whom is angling for a job, in “Who Made Yellow Roses Yellow.”) And yet I want to be Updike’s friend now! Forget the guardedness! Helen Vendler once asked him in an interview about decorum and propriety and taste in poetry, and in particular about the sexual poems in a certain collection that seem a trifle indecorous. Updike said in reply that poetry is experienced in private, and that life is too short to worry about propriety. [His actual words, soaring miles above my ratty paraphrase, are: “I think taste is a social concept and not an artistic one. I’m willing to show good taste, if I can, in somebody else’s living room, but our reading life is too short for a writer to be in any way polite. Since his words enter into another’s brain in silence and intimacy, he should be as honest and explicit as we are with ourselves.”] Well, life is too short to worry about a lot of things — reserve, tact, the advisability of saying in an essay that you are so miserly with your perceptions that you hesitate to imagine yourself golfing with another writer for fear that he would use something you said and that even so you still want very much to be friends with him. I am friends with Updike — that’s what I really feel — I have, as I never had when I was a child, this imaginary friend I have constructed out of sodden crisscrossing strips of rivalry and gratefulness over an armature of remembered misquotation. Which leads me to a point that seems worth making. Friends, both the imaginary ones you build for yourself out of phrases taken from a living writer, or real ones from college, and relatives, despite all the waste of ceremony and fakery and the fact that out of an hour of conversation you may have only five minutes in which the old entente reappears, are the only real means for foreign ideas to enter your brain. If Hippocrates or Seneca, whom I know nothing about, says that art is long and life is short, it means little to me: it is merely an opinion some strangers have had and others have emptily quoted. But if Updike says that life is short, I feel the strength of it with something close to shock. The force of truth that a statement imparts, then, its prominence among the hordes of recorded observations that I may optionally apply to my own life, depends, in addition to the sense that it is argumentatively defensible, on the sense that someone like me, and someone I like, whose voice is audible and who is at least notionally in the same room with me, does or can possibly hold it to be compellingly true. Until a friend or relative has applied a particular proverb to your own life, or until you’ve watched him apply the proverb to his own life, it has no power to sway you.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.