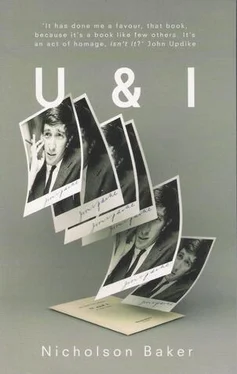

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In August, speaking of clogs, while I was thinking about this essay and not writing it, the sewer in my in-laws’ house backed up. The service, with the appealing name of Another Rooter, had to be called twice. The problem finally turned out to be tampons: their strings caught on a tufty invading root and expanded to the full extent of their puff, about thirty of them. Earthworms took up residence in them — a bizarre gloss on Andrew Marvell. “I found your problem,” the rooter called up nonchalantly, and beckoned me down to an Edenic scene in the lower garden near the standpipe: around the probe of his machine was a roil of roots and black tampon-fruits and pinkly prosperous earthworms. “Best to cut the strings off,” he advised, and wrote “sanetery napkens” on the invoice — our vocabulary always lags reality. And why shouldn’t this very clog clog some narrative of mine? To the worms it was not obstructive, it wasn’t revolting, it was life itself. It is life itself. I’m delighted by the idea that these tampons (which their user treated as Elvis Presley treated his scarves in his decline, barely touching them to his neck before flinging them mechanically out to the audience as souvenirs) underwent this lurid purgatorio out in the garden.

Here again, though, I think I understand what Updike was doing in censuring clogs. When he wrote the review of Edmund Wilson’s diary he was tired of the Proustian and Nabokovian and Of the Farm ian set piece. He was tired of the feel of cranking up those cylinders in himself. The most fertile internal acres of lyrical observation had already been mowed. Increasingly he was interested in the other things novelists are expected to do. Even the very word “clog” shows his impatience with his old self. After a certain point, the management of one’s own past vocabulary, the avoidance of repetition, becomes a major burden. Your earlier formulations become contingent influences — and they hunt you down. An interviewer asked him if he worried in writing so much about repeating himself, and he said something like, You do after a while get the feeling of having been in the same place before. Ah! When I first read that, years ago, I wanted so badly to know that feeling! If, on a dozen earlier narrative occasions, you’ve obstructed the narrative, caused the narrative to hang fire , made it negotiate a trifling embouchement , etc., you finally get a kick out of using the word that you’ve been holding at bay all these years: you’ve earned the privilege of using it — to you it’s fresh, since what feels tired now are your own earlier attempts at freshness. The sheer amount of memory it takes as you’re writing and you pause at some nominative juncture and review the options, and one by one reject those that file before your mind because you clearly recall or dimly suspect that you’ve found an earlier home for them — the sheer mounting strain of this, like the strain of a chess player who has to keep every move of every game he has ever played available for immediate review — must be exhausting. (Updike mentions the theme of suburban adultery that has occupied him since Marry Me , “a subject that, if I have not exhausted it, has exhausted me.” Clever bastard!) It is almost with relief that once in a while we think we have come across a pre-enjoyed image, such as the white crosswalk lines on the street that are pulled this way and that by passing cars in Of the Farm and another book. (The image bears up well under this joint custody, by the way [if joint custody it is: I thought the second crosswalk image was in The Centaur but I wasn’t able to find it there] — though we take to it in part because we feel tender toward it, uncertain of the level of Updike’s devotedness: yes, he liked it enough to consent to it when it appeared in a street scene the first time, and yet he didn’t like it well enough for his memory to warn him off a second placement.) How many hundreds of book reviews has he embarked on — even in the rigidly conventionalized first sentence or two of these exacting etudes forever finding some tilt or pressure of the needle that allows entrance into that scarred and track-marked territory of literary synopsis, correlation, and judgment? I can feel his pride, despite his expressions of relative coolness toward his nonfictional achievements, when he quietly says in the acknowledgments page for Hugging the Shore , that x and y and z first appeared in The New Yorker , along with “ninety-two of the book reviews.” What an astounding number! You know he’s slightly proud of it: there was no reason he had to count them.

At some point, then, at several points, Updike must have felt that panic that the founder of any highly successful entrepreneurial concern feels, when his business has grown so big that he can’t remember all of his employees’ names. The very sensation of that overfertile sump of your own previous usages, a vast dying sea just on its own, never mind the rest of the marine world, begins to force you in the direction of simplicity: you can see this force operating, for example, in an essay Updike wrote for Esquire in 1987, about listening to the radio. (I remember the essay well because, though it didn’t say what I wanted to say, it still came too close to an essay I was doing on the same subject for me to finish mine.) In it, Updike remembers how in the cold car of his childhood (the same car as in The Centaur ), he would “lean into the feeble glow of the radio dial as if into warmth,” and he brings his radio affections up to date by saying that he likes a certain tune by Madonna [“True Blue”], and he closes the sentence of approval with a colon and a single word: “catchy.” A thirty-year-old Updike would never have resorted to that word, because calling a tune “catchy” isn’t on its own interesting enough: the Updike of that era would have exerted himself to find a more refulgent dinglebolly of an adjective as diligently as Whitney Balliett, that tireless prodigy, still does in writing about music. But Updike has chosen “catchy” and it satisfies us in its setting, because he feels and we feel the inversion of word frequency that happens over the course of a life of careful writing, as the near-to-hand and superficially uninteresting become interesting through relative neglect. If you begin as something of a mannerist and phrasemaker, you offer yourself the hope of gradually disgusting yourself into purity and candor; if on the other hand you start by affecting a direct Saxon scrubbedness, then when a decade or so later you are finally ready to cut through the received ideas to say something true, the simplicity will feel used up and hateful and you’ll throw yourself with a wail on the OED and bring up great dripping sesquipedalian handfuls while your former admirers shake their chignons in pity. I know perfectly well that I should not be using inkhorners like “florilegia” when I mean “collection” and “plenipotentiary” when I mean “stand-in” at my age (b. 1957) — and though the latinate conscripts were indeed the ones that first sprang to mind as I was typing those sentences, I did look askance at them on the screen a minute after I used them, for two reasons. First, because their eager scholasticism made me wonder if others would wonder whether my choices had leaped from a thesaurus or one of those maddening block calendars that offer a new vocabulary word every day. (I still find the deracinated adjacency of the thesaurus objectionable, and never use one, and feel guilty when I try to make a dictionary serve the same slatternly function, and I am only tempted to seek one out in the reference section if I strongly suspect that a reader may say “Florilegia? — right, sure, he just looked up anthology , the fraud,” and I need to assure myself that the word I used is not sitting right there three words over from the word I think the reader will sneerily suppose I was wishing to avoid, and even then I resist the urge, because if I do find that the word I want to use is there and I avoid it I will be operating under the influence of Roger’s, too. Yet at the same time I hate all this overscrupulousness and I am drawn to Updike’s honest picture of himself in “Getting the Words Out” as “paw[ing]” through dictionaries and thesauruses, and I similarly admired Barthelme when at the Berkeley writers’ conference he blew Leonard Michaels’s (pale yellow) socks off by casually saying in a question-and-answer session that sure he used a thesaurus, absolutely , I love both Updike’s and Barthelme’s implied boredom with the purist’s pretense that every word he uses has to have been naturally retrieved from a past passage. So I agree with Updike that a thesaurus isn’t intrinsically evil, and yet I can’t use one — and I even feel slightly guilty when I use a certain word whose placement I have admired in something by Updike in roughly the same way he uses it: for instance, I wrote the phrase “consorted in the near vestibules of my attention” in my second novel, and I used “consorted” because one morning I was reading a review of a novel (can’t remember which one) in Hugging the Shore and was struck by a lovely use of “consort” [“… better consorts with our sense of what a writer should be …” in a review of Beckett’s Mercier and Camier ] and again worried, just as I had all those years ago when I read “absurdly shook my head No” that I would never write as well as Updike. But now that I know from Self-Consciousness that Updike regularly uses thesauruses, I’m drawn to show the same dismissiveness toward “consort” that I worry others will direct at my use of “florilegia”: it (“consort” I mean) now feels as if he found it under “adjacency” or some other big rubric, when honestly he could have found it in a thousand places — Henry James is a frequent consorter, for example.) And, second, I looked askance at “florilegia” and “plenipotentiary” because I felt a needle jump in my déjà vu-meter that might indicate that I’d used them both before, and I didn’t like the idea of people (i.e., Updike) thinking, “Florilegia again? It wasn’t that great the first time! He’s pretending his vocabulary is a touch-me-anywhere-and-I’ll-secrete-a-mot-juste kind of thing, when it turns out to be this cribbed little circle of favored freaks that he uses over and over hoping nobody will notice!” So what I have to do now is to search the disks that hold my two novels for the words “florilegia” and “plenipotentiary”—an activity that has to be as artificial as any thesaurus search. Each novel I write will introduce another layer of this vocabularistic panic, and increasingly I will come to recognize the utility of words and phrases that don’t make waves, since their very commonness keeps them from being noted as events that can or cannot be unintentionally repeated; and eventually, one morning when I’m fifty or so, I will be trying to work up my long-abandoned notes for a pop music essay, and I’ll want simply to say that a certain song is good, and the adjectives will line up for the casting session, and one by one I will nod as they twirl past in the half-lit stage, saying I used you, too old, too young, I used you, I used you, I didn’t use you for x reason, I didn’t use you for y reason, and finally, like Hope following all the evils that flap out of Pandora’s box, the word “catchy” will flutter up, “Like a virgin, touched for the very first time,” as Madonna would say, and I will think, Hey! — but then, because I quoted it to illustrate the whole problem of vocabulary management in this essay, I will remember that Updike already used it and that it is off-limits, and, in a wistful non sequitur, I will find myself wishing that I had been Updike’s friend. Catchy, catchy: it is a beautiful word.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.