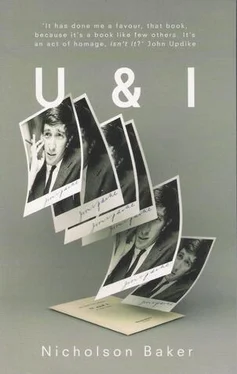

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In fact, at this very moment I have at my left elbow a rubber-banded pile of three-by-five cards, each holding a phrase I remember from Updike, sorted in alphabetical order by key word. I’m modeling myself on Nabokov’s lovable Pnin, who retires to a carrel with one drawer of the card catalog like a squirrel with a nut — and on Nabokov himself, of course, who detailed his three-by-five-card method of fictional composition so comprehensively that Gore Vidal said in some essay that he was sick of hearing about it. I have only to pluck out one of these phrase cards at random, such as presided over by a serene and mutual deafness , Updike’s perfect characterization of Nabokov’s and Wilson’s epistolary argument over poetic meter, to feel that I have dots left to connect, and that I am crisply advancing the cause of self-knowledge. [The correct quotation, however, is “derived from a serene and mutual deafness.”] But when I came to the end of that earlier paragraph, with the vastness of the open sky visible through a rent in it, I thumbed through these three-by-five cards in vain: I found I had no simple way back to Updike. I could mention an aerial description I knew from Many Me that goes (in my misremembered version)

Sally became a bird, a heroine. The clouds boiled beneath her, radiant, motionless. For twenty pages of Camus, while the air conditioner nozzle whispered in her hair, something something something

[and in Updike’s real version:

Then Sally flew; she became a bird, a heroine. She took the sky on her back, levelled out on the cloudless prairie above the clouds — boiling, radiant, motionless — and held her breath for twenty pages of Camus while the air-conditioner nozzle whispered into her hair.]

which I remember simply because I was distressed in 1987 to come across the throwaway mention of the air nozzle in Updike after I had resolved to write in detail about my own reverence for it. (The only other mention I knew of was in John Dickson Carr’s 1951 The Nine Wrong Answers , in which it’s called a “little ventilator” that sends “a shaft of cool air on [the hero’s] face.”) But this sky- Marry Me connection led me nowhere useful. Or I could make an imperious sort of modern transition by first citing Updike’s mention of something that John Hawkes had once told him, which was (approximately), “When I want a character to fly, I just say, ‘He flew’ ” (see, I would never have taken this piece of advice to heart if Hawkes himself had said it to me, because Hawkes’s fictional imagery is too gruesome for him to be a possible friend, but transmitted through Updike I have found it very useful), and by then announcing that I was adapting Hawkes via Updike by saying “When I want to make a transition, I just say, ‘I’m making a transition’ ”—but again there was no promise of riches beyond the pass. Or I could simply rattle on about influence, but I felt that I badly needed a break from that.

So I was left with the word “sky”—and as everything I had still to say crowded tighter around this sudden hole in my essay, shouting advice and pointing urgently off in different directions, I began to notice that the sensation of tumbling into a word like “sky” was not much different from the sensation I had experienced already several times in thinking over one or another of Updike’s phrases: set off on three-by-five cards, they now constituted my universe, or rather my dictionary, and consequently each was prone to an alarming inflation. On one card I have a slightly garbled version of Updike’s Picked-Up Pieces politesse toward his fact checkers: “Many the untruth quietly curbed, the misspelling invisibly mended.” Quietly curbed —simple, beautiful, beautiful, simple! I have reduced Updike’s millions of words to these few flash cards, and like the disembodied idioms that are projected behind the Talking Heads in Stop Making Sense , the isolates I have rubber-banded together can rapidly become too incantatory to retain their standing as exemplars of grace.

But I can always stop flipping through them; I can always leave the rubber band undisturbed: really it is only the physical availability of the three-by-five stack, the fact of it at my elbow, that I need, since it sustains the temporarily pleasurable illusion that I am a graduate student in some delightfully narrow (but fully accredited) course of study and research. As a matter of fact, on the night I first thought of rationalizing my Updike memories on file cards (December 5, 1989), I had an unusually complete dream in which I enrolled in a high-powered Melville seminar at a prestigious university. I caught a glimpse of some of the other seminar participants on registration day: they were all young women, likable-seeming, plain, disturbingly intelligent and well read. I hurried to the dream’s bookstore because I knew almost nothing about Melville and feared humiliation, and I found there a slipcased edition of a slim green and black biography of the author by V. S. Pritchett that I was amazed to see was part of the long-defunct “English Men of Letters” series. Opening it, I thought I saw a copyright date of 1888, but giving it a moment’s thought, I knew I must have misread the century, since Pritchett is still alive, and for him to have written such a book in 1888 would make him at least a hundred and twenty years old now. I pulled it out of the slipcase and opened it; I came to a page that was very thick, like those pretend books you can buy from Barnes & Noble whose interiors have a big hole cut in them to store valuables: there was a printed warning saying “Punch Bound,” and I realized that I was looking at something very similar to the back of a pop-up or “turn and learn” children’s book page, where the rivets and tabs and sliding mechanisms of the understructure are fully disclosed. As I began to turn this resistant page, I saw a soft white whale-tail begin to emerge, made from a three-quarter-inch pile of Kleenexes cut into a tail shape; when I opened further, the rest of the bias-folded cetacean, made out of the same thickness of brand-new Kleenex, rose out of the book and straightened itself out. It seemed odd that the young Pritchett would have felt it necessary to resort to a pop-up to demonstrate what a white whale looked like, but I nonetheless admired the oddity, and I thought that the book, though expensive (thirty-nine dollars), would appreciate dramatically in value because of this feature. I decided I had to buy it: the promise of Pritchett’s careful, unbaroque prose applied to a sloppy but brilliant American like Melville was very exciting, and its lack of critical jargon would serve as a useful corrective to the Melville seminar, filled with supersmart grad students who had read ten times what I had read. I had some trouble getting the Kleenex whale to fold away properly back into the book, and I felt once again the familiar sadness about display items, which in abetting the sale of identical but sealed versions of themselves are treated so carelessly by shoppers that they will never find a buyer of their own, and as a result I decided that I would not put the demo edition back on the shelf and buy the unopened one, but would buy instead this very one I had already fingered, despite the crumpled tail. How exciting it was to be beginning an English seminar after all these years, and after all the scorn I’d felt toward the academic study of literature! And how exciting that all the smart grad students would have read the latest American biography, while I would have the principal events of Melville’s life funneled through old Pritchett’s natty English mind! As I turned toward the cash register, I woke, feeling for once that the term “well rested” had meaning. And that morning, still under the grad-student spell, I located in my office an unopened packet of three-by-five cards that I’d bought several years earlier, having seen them in a stationery store and thought, I’ll never use these guys, but I have to own them anyway. When I was twelve, I saw my mother use a green metal box filled with three-by-five cards in connection with some course she was taking for her master’s degree, and when my sixth-grade teacher told my reading group that we ought to start “building” our vocabularies by writing the definitions of unfamiliar words down as we came across them, I asked my mother for a similar green box and some cards of my own, which she bought for me. I placed the box on top of my desk at school with the clean sense of starting out on a project: coin collecting had lasted two weeks as a hobby, model-airplane building had lasted two years — but now, in word collecting, I thought (mistakenly) that I had found something superior, more permanent, than either of these. For several days I carried the green box back and forth on the school bus, in case I came across a notable word at home, but it was awkward to hold, and I was finding anyway that I was fussy about what words I wanted it to contain. So far the only ones that had seemed worthy of the box were “aesthetic” and “antidisestablishmentarianism,” and the latter I wrote down reluctantly, because it was such a hackneyed longie. I told my father about my new hobby, and I asked him if he knew any interesting words. I was eating an orange, I think. He said, “Sure! You’re starting with a? All right. Here’s a word that sounds like aesthetic: ascetic. You know that one?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.