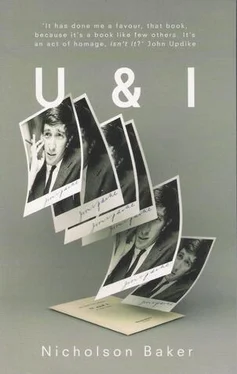

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The sherbety pucker of “acerbic” makes it a better word in some sentences than the more neutrally spirited “acidic”—I saw that; but once my spike of intense joy in having finally remembered the contents of my sixth-grade vocabulary box passed, what interested me was that Updike had used the elegantly curtailed version of the word: acerb. This is so like him, to prefer words like “acerb” and “curbed” that enfold more mental syllables than they metrically exhibit. I naturally can’t check the date because it would mean opening Picked-Up Pieces , but I would suspect that Updike’s use of “acerb” in that sentence was roughly contemporaneous (give or take a year) with my father’s suggestion of “acerbic” to the sixth-grade me. (The conjunction is coincidental, however: my father is not an Updike reader.) And this sort of timeline matching is, for me at least, one of the basic activities that accompany the admiration of writers of the generation immediately preceding my own: I allow myself to move back from the burbling coffee maker of the present instant along those many linked extension cords of personal identity (rustling twenty-five-foot industrial orange lengths that hurt when you step on them in bare feet, with heavy three-pronged ends; narrower-gauge, permanently kinked white or brown varieties, molded from a cheaper sort of plastic, with a faceted multiple receiving end like a burnt-out brown-stone that stolidly resists the intrusion of the average plug) that lead down to the basement of my simpleminded younger self, back to when I sent off coupons to Charles Atlas from the back of comic books and drew plans of the triangular house-on-wheels I was going to live in (with its tiny kitchen and bedroom/driver’s seat at the forward apex, and the huge chemistry lab occupying all the rest); and then into the surplus sockets along this jury-rigged linear continuity I plug in one by one the flashing dates and tides of masterpieces from those years— Revolutionary Road, Of the Farm, A Severed Head, A Single Man , etc.; and once they are all lit up in Vegas colors, it seems miraculous that I could have lived through that same stretch the first time and not seen or felt any of this buzzing signage. Perhaps you never get over the futile hope that you might be able to rewire your earlier unknowing self so that it was linked from the first to all of those high-voltage parallelisms. Of the relatively few written notes I have made about Updike, the earliest one I’ve been able to find (written when I was twenty-five in the third person, partly inspired by the Updike story [“Flight”] about the self-conscious seventeen-year-old kid who “went around thinking about [himself] in the third person”) attempts this very rewiring. I reproduce it exactly here, misuse of “comprise” and all, with one clarification enclosed in brackets:

6/21/82. Harold, reading Updike’s The Centaur, fell in love with the short stOry that comprised chapter two — he thought of 1963, when the book appeared: the nostalgia for Updike’s feelings, at the beginnings of his career, mixed with his own early memories of the house they moved to, his family, in 1963—he remembered sitting on the bathroom floor upstairs, looking through a Metropolitan Museum calendar (one of his mother’s aunts sent one every year); the numbers 1963 had impressed him then: the specific location in such a wash of millenia — he was sitting with his mouth pressed on his knee, which had an odd taste; now he was so un-flexible he had not tasted his knee for over a decade — a datable memory, a memory of the revelation of date, almost as if that moment marked a Piagetian phase. Yet the interesting thing was the connection of this memory with Updike’s own reliving of his childhood memories, and the ache of wanting to have been him in 1963, and to equal him now — yet knowing that he [that is, Updike] was at twenty five far more polished than Harold was; and this sadness mixed with the comparison between Updike’s mother in Chapter two, and as she appears in the other stories (“Flight”), with his own — the very similar relationship, yet the sense that while Updike was at twenty five fulfilling his special destiny, satisfying the pride of his parents with story after story, Harold’s own path was on a steeper, rockier slope — he felt himself, month after month, defining himself on the losing side of the comparison.

The general whimperiness of this passage of mine, combined with the reliance on B-list metaphors like “wash of millenia” [ sic ] and “ache” to keep the prose at a higher verbal pitch than its ideas can hold by themselves, has the ring of vulgarized early Updike, whose boy-heroes are sometimes more sensitive and queasier-stomached than one wants them to be. You feel when one of his young men’s GI-tracts yet again does some unbecoming acrobatic in reaction to a piece of social unhappiness that a writing teacher at Harvard must have told him that it was a good idea to have the reader get his mood-information through all of his senses, and that dutifully he is applying this distorting dictum to excess; just as in movie after movie whenever the character gets a piece of terrible news the scriptwriter immediately has him or her bend at the waist, grasp the front bumper, and (to use an idiom that understandably caught Edmund Wilson’s ear) “snap lunch”—in laziness resorting to brutally externalized physiology because any subtler sort of core dump is so difficult, cinematically and fictionally, to achieve; and yet hardly do I venture this small criticism when I remember a later character, in “Twin Beds in Rome,” I think, who much more believably than his predecessors gets sick on a maritally crucial vacation and can feel in the initial moment of his illness the entire shape of his stomach within him, an unprepossessing tuber —a magnificent trope, which uses an ugly, earthen, marginally-edible-sounding thing to describe the location of the discomfort it would cause if eaten, and which may owe its existence entirely to the whole unsatisfactory preceding series of youthful indigestions. [To my astonishment, I have not found “tuber” so used in “Twin Beds in Rome” or anywhere else I looked; could it be that I made it up? That it is my own image? Doubtful. In any case, the passing sickness in that story works in a way that the bellyaching in The Centaur does not.] “To the stomach quatted with dainties,” said Lyly, “all trifles seem queasie”; and the moral we might draw from Updike’s early prose is that the perfectly healthy, euphuistic wish to caramelize every crab apple and clove every ham ought not to be accompanied by too keen an interest in the hero’s emotio-gastric status. (I write this, needless to say, during the holidays.)

But here again, here again, I have to call attention to this problem of tone. Is it like me to rope somebody like John Lyly into the present context? No, it is not. Or rather, it is only when I can then call the reference immediately into question by a follow-up act of self-reproach. When Beckett allowed his nervousness about Proust to commandeer his attitude, it made him “acerb,” as Updike duly saw; but when I am betrayed by what I take to be a somewhat similar nervousness — a feeling that the stakes are very high, that everything depends on the quality of my thinking right here, that this essay is the test of whether I should bother to be a writer or not, and yet the feeling at the same time that there is a fatal prematurity in so arranging things, since it forces discipleship and competitiveness to clash awkwardly when with time the two would have arrived at a subtler and more composed relationship — the betrayal takes the form of smirks and smartass falsifications, such as when I spoke earlier of trying to “hustle” Updike on the golf course into thinking I was less perceptive than I was, or when I used faux-naïf expletives like “Jeezamarooni!” or called myself a writer “on the make.” I really must read The Anxiety of Influence as soon as I finish writing this, because the fragmentary idea I have of it keeps steering my approach into oversimplifications. It might even be that two of Updike’s own early characters are in large part to blame for my errantly cocky tone — the convergence of contingent and chronic influences being especially hard to shake off. In the story called “The Kid’s Whistling” a kid disturbs the creative concentration of a retail-store manager by whistling blithely while the increasingly irritated manager tries to finish a sign that says something like “Have a Happy Holiday” [“Toyland” actually] in multicolored tinsel on glue [“Silverdust” on poster paint]. (I reread this story in 1987, ten years after I first read it, remembering only the tide, because I needed to be sure that I wasn’t overlapping Updike’s use of whistling in a scene in my first novel. Such checking to control against overlaps is in my experience one of the main motives for the miscellaneous reading that writers do.) And in another early story, which I read circa 1978 and whose tide I can’t bring back [“Intercession”], an overcheerful buttinsky kid messes up the golf game of a somewhat older, more serious sportsman by his running commentary. The Bugs Bunny/ Elmer Fudd pattern of both stories, though it unquestionably does capture a fractional component of the true nature of my feelings toward Updike, is much too easy to ride out into exaggeration — and I am aware too that people would probably rather hear me be smartass, thereby digging my own grave and taking old Updike down a peg or two at the same time, than hear me be grateful and woozily admiring.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.