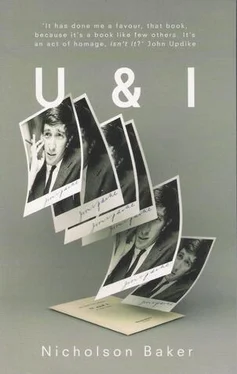

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

(But this isn’t Religio Medici ; Browne’s casualness with direct quotation is not possible now: when I finished the entire essay I assembled all my Updike books, and I took out from the library the ones I lacked, and I tried to locate each phrase I had used. In most cases I regretfully corrected my misquotations — regretfully because my errors of memory were themselves of mild scientific interest to me. During my searches I had to stave off the intense desire to bolster the argument with other quotations I encountered along the way. A surprising number of phrases weren’t where I remembered them as being — for example, I was sure that “vast dying sea,” which I encountered in 1982, was in “Who Made Yellow Roses Yellow,” but I finally found it in “Incest.” And I knew that his sentence about reading “what they told me” in college was in Esquire’s 1989 summer reading issue — it isn’t. Where my argument depends in some way on my misquotation, I have left the error intact and simply corrected myself between brackets: []. If the phrase was not to be found anywhere in a week of flipping and skimming, I resorted to “Updike says something like” and kindred fudgings to indicate that what I’m remembering is only a paraphrase, and may not even exist.)

I was definitely planning to put my Updike thoughts in some order — I was going to do them that injustice, at least — but as I tallied and itemized and found links between the phrases I remembered or misremembered from his books, I realized how fortunate I was in one important respect: though our man had already taken his place on a page of Bartlett’s, no quirk of fame had yet singled out even one tag phrase that would have overinsistently interposed itself between my private recollections of his work and the sort of Familiar Quotation memory-at-large that culture eventually requires as the price of its permanent attention, or simply so as not to be overwhelmed by the infinitude of every literary personality. If I were to pop-quiz myself, right now, “Hey, what about Henry’s brother, old William James — what do I think of him?”—the irritating bluebottle phrase “blooming buzzing confusion” would be first to answer my solicitation, and it would be impossible to wave away, once summoned, in that thought-session. Years of reflection, faculty meetings, mood shifts, changes of profession, trips to Europe, religious doubts, letters from his brother, sensory information of the most varied sort — all of it has been compacted into words that now (through simple overquotation, to which I guiltily contribute here) have no more intrinsic bloom or buzz or confusion than a spherical rabbit dropping suspended in a pyramidal lucite paperweight. And yet when William James comes to mind unbidden, what I think of most often is a time in New York City during the penny shortage of 1981 when the McDonald’s on Seventieth and Second was offering, so a huge sign said in the window, a free Big Mac to every customer who exchanged five dollars’ worth of pennies for a five-dollar bill. I pulled the blankets off my bed and on the smoothness of the bottom sheet counted out five one-hundred-penny piles from the copper reserves I had accumulated in barely a year and had stored in a number of glass custard cups and other amphorae in my room. The pennies so grouped I scooped into five plastic bags, and with my pounds of spare change and an anthology of William James’s writing that I had taken out of the library that very day in hand, I walked to the McDonald’s and waited my turn. But as I slowly drew closer to the cash registers, my elation and amusement at taking McDonald’s up on their offer (and thereby getting a rate of return on my residual earnings, roughly $1.50 on $5.00 over a year’s time, that would have made any mutual fund proud) began to sift away: I was right in the middle of the dinner rush, and there were many rich-looking cashmere-coated women behind me in line whose tempers would snap if my pennies added a further delay. As I feared, when my turn came, the manager was called over, and despite my repeated claims that he didn’t have to count the pennies, that there really were five hundred of them there, he poured out each plastic bag in turn and slid its contents two by two off the counter and into his palm, while beads of sweat appeared on his brow, and the cooking machines beeped their blood-pressure-heightening appeals behind him, and cash drawers sprang open and were pelvised closed and rushed order takers skated around on several mashed french fries underfoot — for this guy was only the manager on duty; he had only inherited the free-Mac offer, he hadn’t conceived of it, he had at most taped up the sign, and he evidently didn’t comprehend its motive, which was the overridingly urgent need for pennies, in bulk, their precise numbers to be determined at the close of business in the leisure of the back office, and not while dozens of well-off, exhausted East Siders curled their lips at my somehow pathetic miserliness, and especially at the sight of my humiliatingly domestic plastic sandwich bags, which looked so out of place, so homemade, slumped anonymously on a counter where every carton and wrapper and cup had a ratifying logo printed on it, as if my bags enclosed stale trouvailles I’d discovered poking through the trash after a church bake sale, or ancient concave baloney sandwiches that my mother had made for me to take to grade school and that I had hoarded all these years in jabbering archivalism — as if, in other words, I was, in my indigent desperation, trying to pawn some unlovely private collection, of value only to me, in exchange for food. When the pennies were finally all counted and I got the free Big Mac and a paid-for drink to go with it, I was fuchsia not only with primary embarrassment but with a secondary more agonizing humiliation at not having been able to pull off this unchallenging public moment without blushing: I reeled to the violently yellow “dining room,” and to escape any stares at my facial coloring I bent very low over the William James book, which I opened randomly at a selection from The Principles of Psychology.

But the moment I began eating, my mortification reversed its engines and transformed itself into a fierce desire to gloat: I was chewing my way through something substantial, tiered, sweet, meaty, that had cost everyone else in the room money but which I had gotten for free. I had a five-dollar bill in my wallet that I hadn’t had before: McDonald’s was paying me to eat here! I wanted to laugh a wicked mean pitiless insane laugh, the kind that some bums, who for some reason always found the sight of me funny, would often helplessly produce, shaking their heads, pointing a finger, as my too-tall, wire-rimmed, pinheaded form caught their dissolutely untetrahydrozolinable eye: among bums I felt like an established and salaried Upper East Sider, but among Upper East Siders, I felt I had hugely swollen ankles and tattered back issues of magazines projecting from several pockets and dirty bandages hanging by one wing on my face. And contributing at least half of this joyful inburst was William James himself, who, it turned out, was really good : unpretentious, jolly, at his ease — as smart as, but completely different from, his brother. I came to a page with an illustration — a number of shaky curved lines all traveling by different routes from a point A to a point Z —meant to illustrate the various paths that the recently christened, pre-Joycean “stream of thought” might take in moving from one established idea to another. It was a glorious sight. The confident, lighthearted didacticism of this small drawing made me shake my head with instant affection for William James; I thought of him frowning over it, attempting to capture by the tremble in his execution the irregular uniqueness of each thought path, prouder of this artwork perhaps than the prose that led up to it, because his first wish had been to become a painter; and I thought of those several contemporary illustrators whose style was based on the same trembly, Dow-Jonesy contour line: William Steig, for instance, and Seymour Chwast, and whoever did that Alka-Seltzer cartoon commercial in the sixties in which (as I remembered it) a yiddishly unhappy human stomach, gesticulating from an analyst’s couch or chair, its esophagus waggling like an unruly forelock, told its troubles to a nodding murmuring doctor; and I thought also of the frail, capelli d’angelesque decorative markings a professor of philosophy at Haverford, Richard Bernstein, used to leave behind on the chalkboard as he “gave some texture to” an argument in Popper, Lakatos, or Paul Feyerabend — filaments of faint connectivity that visually supplemented the lengthy meditative “ee-ee-ee-ee” noise that he used to extend his favorite transitional phrase, “in a certain sort of way.” In a certain sort of way-ee-ee-ee. Now, when William James enters my thoughts unexpectedly, the accompanying image most often takes this form, as the sight of the drawing on that right-hand page on that evening at McDonald’s. And yet the major coincidence of the occasion — the explicit exchange of pennies for thoughts, the sudden, specially sauced incarnation on Seventieth Street of that formerly empty saying — did not make itself felt to me until this year, as I worked on my second novel, in which small change figured, against my will, as a minor theme, and I finally recognized, with disappointment conjoined with gratitude, that this previous William Jamesian memory explained to some degree why pennies and their brethren seemed so strangely evocative to me; disappointment, of course, because one always wants one’s fascinations to come originally from life and not from the library. And when, this year as well, I made some smalltime publicity appearances in connection with my first novel and was typically, Americanly inarticulate — indeed, worse than typical: tongue-tied, “um”-saying, jargon-ridden, flatvoweled — when I saw the eyes of the radio interviewess widen in alarm as the stretch of dead air lengthened, and when I compared myself miserably with an amazing performance by Updike on Dick Cavett that I recalled from the late seventies, where he spoke in swerving, rich, complex paragraphs of unhesitating intelligence that he finally allowed to glide to rest at the curb with a little downward swallowing smile of closure, as if he almost felt that he ought to apologize for his inability even to fake the need to grope for his expression, and for inspiring the somewhat frantic efforts Cavett made to keep archly abreast of this unoratorical, uncrafty, generous precision; and when I compared my awkward public self-promotion too with a documentary about Updike that I saw in 1983, I believe, on public TV, in which, in one scene, as the camera follows his climb up a ladder at his mother’s house to put up or take down some storm windows, in the midst of this tricky physical act, he tosses down to us some startlingly lucid little felicity, something about “These small yearly duties which blah blah blah,” and I was stunned to recognize that in Updike we were dealing with a man so naturally verbal that he could write his fucking memoirs on a ladder! — when, as I say, I compared myself very unfavorably to Updike’s public manner after my own radio disasters (I heard myself over the car radio and had to pull over on a side street and get out and shut the door on my upstate voice, which I was tape-recording), I repeatedly comforted myself with a thing against spoken eloquence from Addison that I had read in Boswell: “I have but ninepence in my pocket,” it roughly goes, “but I can draw on a thousand pounds”; and the fiscal simile here too attached itself to my idea of William James, whom I thought of, wrongly no doubt, as struggling for expression, or at least for a form proper to his style of reasoning, while his gay brother unfumblingly dictated sentence after incredible sentence to his typist.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.