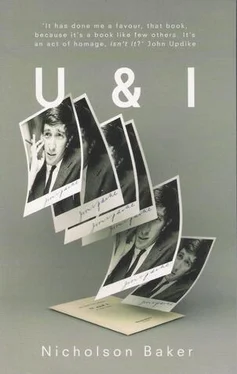

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Yes.” He blinked. And then very politely, knowing that it was what I wanted him to do, he asked, “And what were you doing at The New Yorker ?”

“I have a story coming out pretty soon, too. So we’re fellow contributors.”

“And what’s your name?”

I told him.

“And what issue is it?”

I told him.

“Good,” he said.

“And I’m his mother!” said my mother, waving. (Why didn’t I do the proper thing and introduce her?)

Updike nodded at us both. “I look forward to reading it,” he said, giving us back his novel. My mother and I smiled good-bye and walked away, with flushed, What-new-fields-can-we-conquer-now? faces. “Well!” my mother said. “Wow! That was a lot of fun! Was that all right do you think?”

“Yeah, it was good, I think,” I said.

Behind us, Updike went on signing, signing.

When I told the story of this meeting to my wife a year ago, she slid down in her chair with her hands over her face in mortification. “I would never have done it,” she said. “But you’re different from me.”

9

I would never have done it either — drag in The New Yorker name so obviously to get his attention — except that life was too short not to. Those ticking seconds of signature might be the only chance I would ever get to embarrass myself in his presence. When the excessively shy force themselves to be forward, they are frequently surprisingly unsubtle and overdirect and even rude: they have entered an extreme region beyond their normal personality, an area of social crime where gradations don’t count; unavailable to them are the instincts and taboos that booming extroverts, who know the territory of self-advancement far better, can rely on. The same goes for constitutionally ungross people who push themselves to chime in with something off-color — in choosing to go along they step into a world so saturated with revulsions that its esthetic structure is impossible for them to discern, and as a result they shout out some horrible inopportune conversation-stopper, often relying on a word like “pustulating,” when natural Rabelaisians — who after-ward exchange knowing glances with each other that say, “Sad— way out of his league”—know to keep their colostomy sacks under wraps for the moment. Which referenced sacks bring us to the second time I met Updike — for I did, as it happened, get a further opportunity to embarrass myself.

At the offices of the Harvard Lampoon , in November 1984, I sprang out in front of him near a plate of ham cuttings as he was hurrying to leave the post-Harvard-Yale-game party. A friend (insofar as male friendship is possible) said I should come with him to this party because the building was worth seeing. As he showed me around, sensing my testy inner readiness to see the Lampoon’s flaws and its self-satisfaction, he bad-mouthed the institution severely — nobody really good except Updike came through here, he said, gesturing at the second-floor library, where all the Benchleys and more recent wizards were shelved. It was true that the idea of working on a college magazine would have been inconceivable to me at Haverford. (Well, no — in fact I once submitted two poems to the literary magazine, which were rejected.) Why waste weeks working on something that is distributed internally, that doesn’t appear on a transcript; something that doesn’t count? It’s like putting on plays for your family; it’s grade-school stuff. But clearly the Harvard Lampoon did count in New York: Updike himself said once (I think) that a New Yorker editor had noticed something of his, light verse perhaps, in the Lampoon and had written asking to see more. And he had done the introduction to an anthology of Lampoon humor — he obviously thought of it as something worth thinking about even after he had graduated. Yet his physical presence that day was, to me at least, completely unexpected. Did he come every time the game was in Cambridge ? Had he actually been to the Harvard-Yale game that day? God I hoped not. It was very important to me that this postgame Lampoon visit was not typical Updike behavior — I wanted him not to have anything to do with writers’ conferences, literary awards committees, college reunions, magazine anniversaries, idiotic flag-waving school spirit: his only allegiances should be, I think I thought, a Craigenputtock purist myself by force of my own obscurity and isolation, to the isolated writers he liked: Henry Green, Nabokov, Tyler, Proust, Murdoch, Melville. And yet if he hadn’t felt enough fondness for his old school magazine to show up that day, I wouldn’t have had my chance to wait for him near the ham tidbits, steeling myself to be pushy. I knew it was pointless, but I wanted to talk to him more than anyone else I didn’t know. I spied on him as he stood in a rearward room, giving serious advice to an exceedingly tall person who was editor or president of the Lampoon that year. Then he took his leave of everyone and briskly walked along the long neomedieval table of hewn food toward the door. He was done socializing; I could see that. But I sprang out anyway. I blocked his path, standing with my hand held out for him to shake. Yes, the editor/president with whom he had been in close conference was very tall and skinny; but I was very tall and skinny too — perhaps taller, skinnier! I needed my outsider’s moment!

“Hi, I’m Nick Baker.”

“I’m John Updike.”

“I know.” (This “I know” is a faint source of shame to me now, but it is nonetheless what I said.) “We met once in Rochester, but very briefly.”

He nodded, still thinking he could escape by giving the general appearance of hurry. But I wasn’t going to let him go. “I, um, had a story in The New Yorker a long time ago.”

Resigned to this standard interchange (“people who want something from me” is one of the categories of humanity he lists in “Getting the Words Out” as not inspiring him to stutter), he asked me what the story was about. I told him, and he said, “Mmm,” but he didn’t look as if he remembered. He asked me my name again. I told him and mentioned the long story I had had in The Atlantic , too. Closing his eyes, pressing on his forehead with his index and thumb, he forced himself to recall who I was. “Didn’t you also write a story about some musicians on the West Coast?” he suddenly asked.

Surprising as this may sound, I had to think for a second. It was a work I didn’t want to exist. Both The Atlantic and The New Yorker had rejected it, as had many little magazines; it had finally appeared in a place called, emblematically, The Little Magazine , where John Gardner had seen it and included it in the 1982 volume of Best American Short Stories that he edited before he was killed on his motorcycle, too soon for me to get around to writing him a thank-you. In his introduction Gardner called it “very slight” (he also called it “beautiful,” but naturally I paid no attention to that); he almost apologized for including it over other more “major” entries. That soured me on it — I didn’t want to be a lightweight. But the main reason I had tried to forget about the story was that it was, by a hair, my first published work, appearing a week or two before the story in The New Yorker , and I was extremely sensitive then to the fateful progression in which (see Updike, Helprin, Gill, and the others) a writer has his first story published in The New Yorker and lifts off from there into a string of successes. When The Little Magazine came in the mail on that November day in 1981, incontrovertibly first, it was an evil portent: in a stroke it condemned me as a late bloomer, a come-from-behind guy. Now when I collected my stories in a book (if I ever published more stories, which by 1984, when I stood in the Lampoon building, was looking doubtful, since I wasn’t writing much of anything by then and the The New Yorker and The Atlantic had rejected or bought and shelved the few pieces of fiction I had sent out), I would either have to leave out the Little Magazine story entirely, or I would have to begin the book with it, since, in another case of copyright-page anxiety, I was determined to do just as Updike had done [on the copyright pages of The Same Door and The Music School ] in proclaiming that “They [the stories] were written in the order they have here.” I had more or less decided to leave the story out. The extreme childishness of my attitude is obvious to me now, because once you’ve published a book your dignity’s dependence on magazines temporarily disappears, but back then the columbarium-like array of quarterlies, displayed on angled steel shelves or in piles on tables or in echoing alphabetization in places like the University of Rochester’s periodical reading room, subscribed to and renewed when necessary and stamped with the date received and warehoused and eventually sent to the bindery and put on other, more inaccessible shelves whose lighting system was often controlled by little oven-timers you had to turn and whose insistent grinding rushed you to your next call number, threatened me with annihilation. All those arbitrarily evocative names (once, under the influence of poetic titling habits, pop groups gave themselves and their vanity corporations and their albums colorful concrete noun-names, but at some point the balance shifted and little magazine titles began to seem instead derivative of pop practices), and all the regional awards, all the calls for manuscripts in the classifieds of Coda (now Poets and Writers ), all that awful, awful young writing like mine that should never have been published, and the contributors blazoned on the covers as if they were big-drawing names when they were utter unknowns like me, and the general conviction that most of the publications were, even more so than the Harvard Lampoon , places that just didn’t count, weren’t read, had no reason for being, made me determined to keep my indiscriminate distance from all of them. So when Updike finally remembered who I was on the strength of that Little Magazine story I was taken aback — I didn’t know for an instant what he was talking about. “Musicians on the West Coast?” I said, puzzled, and then, realizing that I probably appeared to him to be pretending to have to make an effort to remember something that I really knew right off the bat, I said, “Yes! Right! I did!”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.