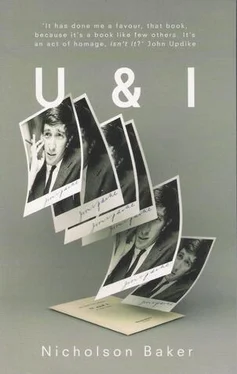

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

8

“Also, homosexuals,” my mother once very uncomfortably explained when I asked her what one was, after reading a Dear Abby column circa 1965, “often have unusually intense relationships with their mothers.” That observation, which still seems quite true, used to worry me, until Updike’s example slowly sank in, and I realized that straights could have strong maternal dependencies as well. My mother is very important to my writing life. She first told me, when I was still in grade school, and long before I had heard of Fitzgerald or Hemingway or Mailer, about a mysterious set of forces called “the enemies of promise” that brought writers low, especially in America; and when I finally read Cyril Connolly’s book by that name, a few months after The Atlantic and The New Yorker accepted stories of mine in 1981, determined (in my expectation of instant celebrity) to be on guard against “the slimy mallows” of success and the “blue Bugloss” of journalism and the “nodding poppies” of indiscipline and chemical addiction and the rest of the besetting vocational dangers that it so winningly lists, I felt I was remembering a moral universe older and more primary than Aesop. Even these days, when I reread the 1960 Anchor paperback reissue, attractively subtitled “An Autobiography of Ideas,” originally bought by my grandfather and now stained by a transparent liquid that seeped out the slackening mouth of a narrow pumpkin I had placed protectively on a stack of books in the window one Halloween when smashing was in vogue in the sixties and hadn’t bothered to throw out for weeks (the hardbound of Cousteau’s World Without Sun was also badly warped by the same Halloween syrup, and a fancily printed signed bibliography of Bernard Berenson was slightly foxed — and whenever I come across a book in my mother’s bookcases that clearly evidences the part it played in supporting my one indoor pumpkin I feel a special thankfulness and affinity for it, as if the pile hadn’t been random after all but prophetic of links and influences that in leaving their timed-release mark on me had allowed me to leave my vandalizing mark on them as well) — even now, rereading, I’m surprised to find that Connolly’s funny, hung-over, peremptory, friendly style, and the scarily chronological lists of books he offers from the first third of this century (that is, the period of his own youth), and the battle he describes between the mandarins and the vernacular you-men (“Is there any hope? Is there a possibility of a new kind of prose developing out of a synthesis of Orlando and the Tough Guy?”), and the occasional injections of his own life (like the plane tree in the sultry garden under which he begins the first chapter, and his description of himself as “a lazy, irresolute person, overvain and overmodest, unsure in my judgments and unable to finish what I have begun”), all affect me with an unexpectedly intense level of emotion. I wish I had known him. I wish he had written about Updike and Nabokov. I wish there weren’t such things as older and younger generations and the inevitable deaths that make you think you have some special connection with a writer just because a pumpkin of yours once rotted on his book. I seem to think that if I don’t turn out to be like Updike, who successfully feinted past every single enemy of promise there was (though the “charlock’s shade,” or sex — adultery in his case — did seem to give him some insomnia.… ah! — another link between Nabokov and Updike and Updike and me: insomnia!), then I will become a picturesque failure like Connolly. But no, I am even less like Connolly than I am like Updike: I’m not a drunk and in fact have a growing paranoia about liquor, I didn’t have a string of successes in high school that rendered the rest of my life anticlimactic, and I haven’t gotten sucked in to book reviewing. When fame and the other enemies do seek me out, though, and oddly enough they don’t seem to be doing so yet, I will be fully prepared for their terrors, thanks to my mother and Cyril Connolly. Updike’s mother, or rather her fictional equivalent in the story “Flight,” tells him, as they stand on a hill overlooking their town, that everyone else is stuck there, but “You’re going to fly”—and here perhaps is one of the more important differences (aside from writing talent and intelligence) between Updike and me: Updike’s mother tells him what great things he’s going to achieve, flying off to Harvard and The Nuevo Yorker , while mine simply assumed the great things and was already thinking ahead to their negative consequences. We didn’t subscribe to either The Atlantic or The New Yorker when I was growing up; I read Look, Life, Advertising Aye, Car & Driver , and Popular Photography. “Promise is guilt — promise is the capacity for letting other people down”—perhaps with these words from Connolly tolling in her memory, my mother, wanting me to have a good life and be a good person and not to fret too much about disappointing expectations, avoided hilltop predictions and other allusions to my promise, except that she told me more than once about a time in nursery school when I had drawn a picture of the three bears in which the trio weren’t presented standing side by side in diminishing size, but were superimposed one in front of the other, indicating (to her) competencies in spatial manipulation beyond the nursery school level, and about another time that same nursery school year when I made a three-tiered organ keyboard by snipping three fringed lengths of paper and taping them together, each one layered over the next. “You were a special little kid,” she said once. Why bother to pretend to be like Rabbit? [“Intellectually, I’m not essentially advanced over Harry Angstrom,” Updike says in an interview.] He knew he was going to fly! And I knew I was a special little kid! We had great mothers! One way or another, we both knew we had promise! (Note the phonetic similarity of The Enemies of Promise and The Anxiety of Influence. ) And Updike did then disappoint — not us, but his mother: he said somewhere that his mother still liked those early stories [or rather, his first New Yorker story] best of all the things he’d done; and I remember being struck by a passage in “Midpoint,” a long autobiographical poem accompanied by deliberately indistinct pictures of Updike and his mother, in which she, or a motherish woman anyway, accuses him of writing about ugly things, [“you fed me tomatoes until I vomited / because you wanted me to grow and you / said my writing was ‘a waste’ about ‘terrible people’.”] Yet, in spite of his having let her down with some of his later work, which was unavoidable, he kept at it: and that is what is so magnificent about him as an example for the rest of us. He knows that some of his books are better than others, and he has even gone so far as to say (I first heard it on the 1983 PBS special about him, but I think the sentiment also appears in Self-Consciousness ) that his best things, his ticket to immortality, are probably his early short stories; and yet, even knowing that, he has gone on writing. He quotes with approval a bracing sentence from Iris Murdoch, something about the writer moving on to write the next novel in order to make hasty amends for the last. He has brilliance and longevity.

But his mother, I learned just last week, is now dead. She died in October. My wife told me that there was a review of her last novel in The New York Times Book Review (January 14, 1990), which I can’t read because they interviewed Updike in a sidebar, and I know if I turned to that page, I wouldn’t be able to resist reading what Updike said about his mother, and then I would have again to apologize for not adhering to the principles of closed book examination. Plus I would be visited by highly unwelcome imaginings of what life will be like when ( if , I still think) my own mother dies. I first heard Updike’s voice in 1977 on a PBS radio show I turned on by chance — and what was he reading? He was reading a Mother’s Day tribute to mothers before some national motherhood association. ( Where is this speech? I haven’t seen it in any of his collections.) I remember thinking, in surprise, Well, how very embarrassing for him! But over time I began to think of the speech as brave and ballsy. It was just as brave and ballsy for Proust to write about waiting for momma to come upstairs and tuck him in; but Proust’s example simply couldn’t have carried weight with me. Unless somebody like Updike (i.e., living and talented and heterosexual) had written about his mother, particularly in “Museums and Women” (one of my mother’s favorite stories), I could not have written about mine — and, more to the point, I couldn’t be writing about mine here. Without Updike’s example I couldn’t right now state how often over the past ten years my mother and I have talked about Updike— long Sunday-afternoon phone conversations between Boston and Rochester during which, after saying “I know we’ve already said this, but …” we covered once again one of our three main Updikean themes. These were, as my mother articulated them: (1) it was good for me to have to plug away at nonwriting jobs — Updike would have benefited from the same necessity; (2) Updike wrongly took sexual advantage of his irresistible prestige as a young writer to poach on suburban marriages while the husbands were off at work; and (3) my reluctance to go into all the bad things in my childhood — the parental fights over money, the dunners ringing the doorbell, the mess and the Saturday-morning fight about the real source of the mess, etc. — was admirable and kind of me but bad for my writing, because it severely limited my range: I should try, she said, to do more as Updike did by telling the bad and not worrying about the hurt this breach would cause. “Dad and Rache [my sister Rachel] and I will be very brave,” she would say. And I would answer, “But there is nothing bad to tell! Some money squabbles — so what!”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.