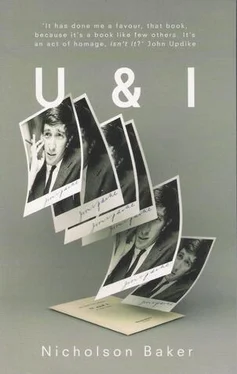

Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - U and I - A True Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Granta Books, Жанр: Современная проза, Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:U and I: A True Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Granta Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

U and I: A True Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «U and I: A True Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a very smart and extremely funny exploration of the debts we owe our heroes.

U and I: A True Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «U and I: A True Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I think you’re smarter than he is, but that he’s a better writer than you are,” she said.

I nodded slowly, wounded, but pleased by her brave willingness, in the name of truth, to inflict such a wound and to muffle it so cleverly with a giant, distracting compliment. She thought I was smarter than Updike — I could live with that! Smarts, pure octane. I would go to the moon with them. But then, a month or two later, at home before starting my job, I was bothered by an identical doubt after reading some of The Same Door. Wasn’t I a better writer than Updike had been at my age? I asked my mother.

There was a silence.

“But you have to think that!” I said. “I need you to think that.”

“I think you will be a better writer than John Updike — I have every faith that you will be a better writer than John Updike.”

That wasn’t what I needed to know, though; the present test was everything. I went off and lay on the floor near the loudspeakers for three minutes, in acute distress, letting the truth sink in. Then I went back to the kitchen and told my mother what my now-wife had said when I had asked her the same question.

“Well, yes!” my mother then said with evident relief. “Good for her. That’s a good way to think of it.”

And so I got several years of self-propulsion out of thinking that I was, if not a better writer, at least smarter than Updike. When my psoriasis turned inward, arthritizing first one knee and then a hip and ankle joint, I took this to be a manifestation of our difference: he had the surface involvement — style — while I had the deep-structural, immobilizing synovial ballooning of a superior mind. This psoriatic opposition still sometimes helps me to go on, but I am increasingly unsure what it means. It means something: despite all those claims (as in Trollope) that intelligence is a secondary trait in the novelist, I find I am much more liable to perk up when I hear that such and such a book has that particular quality than if lyricism, humor, compassion, atmosphere, period detail, etc., is claimed for it. No word so instantly reinforces my existing sympathies: I almost shouted with joy when I read someone quoted in a TLS a few years ago as saying, quite believably, that Proust was “the most intelligent person who ever wrote a novel.” And I ordered Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library entirely on the strength of another TLS review that ended by saying, “Few novels in recent years have been better written, and none I know of has been more intelligent.” The novel is the greatest of all literary forms — the most adaptable and subspecialty-spanning and roomiest and most selfless, in the sense of not imposing artificialities on its practitioners and letting the pursuit of truth pull it forward — and as a result one recognizes the need to posit a certain variety of accompanying intelligence that is itself more adaptable, more multiplanar, sloppier, more impatient of formal designs, roomier, and more truth-drawn than other kinds, a variety that Proust, for instance, has a whole lot of. But what I have only slowly begun to see, over the past five years, is the dreadful degree of inefficiency and outright waste there is in the transmutation of this invisible and evasive, but real, intelligence into a piece of readable prose. You have to be at least twice as smart internally as you hope to be demonstrably in your writing. Therefore, in judging Updike’s aptitudes that afternoon in the cafeteria, my now-wife was undershooting their true magnitude by half. Updike is a better writer than I am and he is smarter than I am — not because intelligence has no meaning outside the written or spoken behavioral form it takes, but because all minds, dumb and smart alike, do such a poor job of impanating their doings in linear sentences.

Yet there is one specific point of similarity between Updike and me that is more important, from the point of view of my own novelistic ambition, than the others (class standing, geographical origin, race, etc.). Most good novelists have been women or homosexuals. The novel is the triumphant evolved creation, one increasingly has to think, of these two groups, who have cooperated more closely in this domain perhaps than in any other. This important truth couldn’t hit us over the head until fairly recently: my own generation was the first to grow up with hard-core stars like Annette Haven a mere seventeen-year-old bike ride away, but more important, we were the first generation to grow up exposed to the range and subtlety and complexity of distinctively gay interests and ways of acting. These became common knowledge: they were no longer sexual semaphore among a gay elite, but were now a constant subject of discussion, delight, disgust, amusement, and enlightenment across an entire educated middle class. Our generation, I think it is fair to say, thinks it knows more about the moeurs of gaiety than any group so big and so mixed ever knew before, and armed with this marginally more sophisticated and less sniggering knowledge as we read past minorpieces and masterpieces, we gather hints and leap to conclusions with a confidence that would have horrified Edwardian bachelorettes. And slowly, with dawning amazement, as the results of our various informal surveys come in, we realize how staggeringly disproportionate our debt is to gaydom, in every possible area of literary deportment, but especially in the novel; and we mingle this knowledge with the long-recognized preeminence of women in the invention and perfection of the form, and we begin to get the uncomfortable sense, if we aren’t gay or female, that we may have chosen a field we can’t quite master. Heterosexual male novelists don’t for the most part really get it , instinctively: they agree with Jane Austen that the novel is a magnificent thing, toward whose comprehension all other forms of writing, and indeed of art, aspire, and this big-time grandeur attracts them, but they find, much to their perplexity, that they can’t internalize and refine upon its ways with quite the unstraining unconscious directness they displayed when thrashing happily through earlier intellectual challenges. At first they blame their false starts and archnesses on their own inexperience and continuing apprenticeship, and they redouble their efforts, but little by little they come to see, at first dispiritedly and then soon righteously, that they “stand outside the tradition”—that it is in a fundamental way alien to them. But they are smart, and ambitious, and hardworking, some of them, and they find that they can bleed off and redirect some of their other proficiencies in order artificially to bulk up the central novelistic understanding they want so badly and don’t innately possess. They stretch the stretchiest of all forms so that it embraces what they do well. And finally they produce things that are, though great, oddities: Ulysses, War and Peace, Pnin. In a field, then, in which heterosexuals end up so often on the periphery — as the legal counsel, drunken reviewers, imitative followers, codifiers, interpreters, academic apologists — for homosexual greatness, a person like Updike, who can be as tarabiscoté as George Saintsbury or Henry James, as foxily ironical as Lytton Strachey, as stylistically up to snuff as Pater, as metaphorically mother-witted as Proust, as zealously thematic as Melville, and who is thus in the same league at least with the bachelor-adepts of history, becomes supremely important to a writer like me, as a model of a man who has in his art successfully moved outside the limitations of his carnal circuitry.

I offer this line of argument tentatively, with every expectation that I will be laughed at for believing in so primitive a form of sexual determinism; it seems, however, unusually convincing to me at present because many of the novels that I’ve liked lately ( The Beautiful Room Is Empty, The Swimming-Pool Library, A Single Man ) have been so directly premised on gaiety: you feel their creators’ exultation at having so much that wasn’t sayable finally available for analysis, and you feel that the sudden unrestrained scope given to the truth-telling urge in the Eastern homosphere has lent energy and accuracy to these artists’ nonsexual observations as well, as if they’re thinking to themselves, Well fuck it, while I’m humming along at this level of candor, why should I propagate all the other received fastidiousnesses? Truths are jumping out at me from every direction! My overemphasis on sex is leading me back toward subtler revelations in the novel’s traditional arena of social behavior, by jingo! (Have people talked, incidentally, about the prompting influence that Angus Wilson’s Hemlock and After may have had on Lolita ? Nabokov must have seen this gay book from 1952, in which the sole pure baddie is the heterosexual child molester, and thought that it was finally possible to amplify his reluctantly incinerated short story and show, now that gaiety was to an extent fictionally normalized, that even Humbert’s unthinkable perversion was more complicated and remorse-filled than Angus Wilson had made it out to be. Nabokov must have noticed how the undisguisedly gay angle of attack lit the old, overnovelized mores from new angles, and that a similarly reawakened sense of nanomanners might result from a fictional situation whose raking unthinkableness stirred his own endocrines more.) Of course, Edmund White’s apostrophe to the narrator’s boyfriend’s bottom (in a recent story in Granta ) would not have been possible without Updike’s wide-screen description of a neighbor’s pussy; but nonetheless it is the homosexual novel right now, perhaps to an unusual degree, that seems to be driving us all toward advances and improvements.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «U and I: A True Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «U and I: A True Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.