He avoided her eyes but tried to look bewildered. He had been considering a certain decision for the past few days, and perhaps this was a window in which to broach it.

“In New York.” She faced him. “Remember?”

“New York, yes …” He put his hands on his hips and blew out a firm sigh. “I was thinking about that. I was wondering if it wouldn’t be best to stay here.”

Gracie stared at him. “But we agreed, there is nothing for us in Bombay—”

“No, I mean that we could move back here. Into my mother’s house.”

“Here?” Hers was a tone that one might employ in reference to a leper colony. She took her hand off the tree, as if it, too, repulsed her. “Did your mother ask you to do this?”

“Of course not. But I don’t want her to be alone.” He gathered himself. “And what is so wrong with my mother?”

“Nothing. She is fine, much better than mine. Though she did tell the neighbors that Anju looked like a hairy matthangya in her baby pictures—”

“Old people have a different sense of humor.”

“The point is not your mother, but mine. My mother and my father, they can’t even look at me.” And here, she stopped herself and began again. “You and me, we were going to start our life somewhere else. Away.”

“We did go away.”

“Bombay was a bad start. But if we come back …” She looked at the leaves, as if addressing them. “I was not meant to be here. I was not meant to live near the very people who turned me out.”

“Don’t be hysterical. You are their daughter.”

She shook her head slowly, a gesture he hated, as it made him feel small. “People can disown their children gradually, over time, so that no one has to notice.”

“Why is everything so complicated with you? Other husbands, they make a decision and the family agrees. The wife moves into her husband’s home. She follows him around. What do we have in Bombay? What do we have in America? Just some drama woman you know whom I never even met.”

“She’s not some drama woman.”

“Yes I know. She’s Bird.” Melvin plucked a leaf and folded it into smaller and smaller halves. As with all their recent fights, Bird’s name had a maddening way of entering the conversation. This was the woman whom Gracie had called her best friend, her Chachy, someone who understood her, details that did not amount to the Bird that he remembered from the stage.

As always, Gracie came to her friend’s defense. “She’s doing very well there. I’m sure she gets auditions.”

“And is that what you want? Auditions? Bird? Over your own family?” He felt a familiar question crawling up his throat, and though he could usually force it down during fights like these, this time, the picture of Abraham Chandy returned to him. At a loss, Melvin asked, “Why did you marry me at all?”

She looked up at the sky for patience. “Because it was time to marry. Now who is being melodramatic?”

“I don’t mean why did you get married, I mean why did you marry me? Didn’t you ever …” He thought he had known the answer, but recently, he had begun to doubt. “I thought this was a love marriage.”

It was her turn now, to stare at him, bewildered.

“You loved me?” she asked.

“Well, yes. And I thought you could have chosen someone much better, much wealthier, like Abraham Chandy.” She seemed to flinch at the mention of Abraham, but he went on. “But you didn’t because you … because I had made some impression on you.”

“When? What impression?”

“At the show. When we spoke. In the audience.”

“You thought I loved you?” she asked. “Because we had a chat?”

“Why did you think I wanted to marry you?”

“For the same reason that other men did. My father, our house, our money, our name—”

“No, that was not it! Those were not the reasons at all! I loved you. And I thought I could save you from that violent father of yours—”

“Violent?”

“That bruise. On the corner of your eye. I remember it still, that color, how you tried to cover it with paint. I married you so I could save you, so you would never have bruises like that again.”

His outburst left her without words.

“You didn’t give me an answer,” Melvin said. “Why did you marry me?”

Her face was full of a pity he had never seen across her features. This was worse than the slow head shake. He felt like a child, her secrets held in fists behind her back.

“Tell me,” he said.

“My father struck me only once. The day your mother called to say that your family was interested in me. At first I refused to meet you no matter how my mother pleaded. My father listened very quietly, he didn’t say a word.”

“Excuse my stupidity, but I am asking why you married me….” And then the answer hit him in the chest, stealing him of every sure breath. Looking at her, he wanted her to stop, but it was too late, her lips were parting with the truth he had demanded, assuming that the truth would repair every wrong.

“And then came the bruise,” she said softly. “I married you because of it. If I kept saying no, I didn’t know what would come next.”

FOR TWO DAYS, Melvin feigned sickness so that he could stay away from as many people as possible. He wanted to speak to no one. He slept in the sitting room. His strategy worked so well that Ammachi was constantly following him around with a bowl of broken rice gruel, and when he wasn’t looking, sprinkling his scalp with rasmadthi powder.

He could not meet Gracie’s eyes. In her face was the life he had wanted, but what did his face hold for her? Stupid, misguided gallantry. He had never wondered why she had the bruise but was convinced that he would save her from receiving any more. He had recalled his aunt, whose husband obeyed no rationale as to why or when he dealt his blows.

And Gracie had never loved him. Theirs was not, after all, a love marriage. He tried not to be too sentimental about this discovery, but he felt a fool in front of the one person whose intelligence had both humbled and pleased him. No matter how long he pondered the question, he would never figure out why her parents had forced her to marry him, the fool, the son of a lorry driver, the hotel clerk with no name.

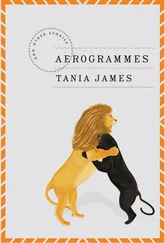

ON THE MORNING before their return to Bombay, while Gracie was running errands, he found a pale blue aerogramme on top of the dresser, sealed and addressed to Bird. Without another thought, he held it up to the lamp to try and decipher the writing, but three layers of translucent Malayalam made an impenetrable wall. He thought how easy it would be to steam the thing open over the stove. Immoral, yes, but who was this Bird to weasel her way into their life, to widen the cracks that already existed in their marriage?

What were they conspiring?

And here he stopped. He left the letter alone. For him, truth was not freedom. Truth bound you up in shame.

Later in the day, while Melvin folded his shirts for packing, Gracie attempted a cheery babble in his direction. “… and did you know the price of an egg has gone up by fifty paisa? But I know how your mother likes mota curry, so I bought a half dozen.” She paused, noticing the aerogramme on the dresser. “My letter. I forgot to send it.”

He glanced at the letter and went back to folding. She was staring at him.

“Did you read it?” she asked.

“It is not addressed to me, so no.”

She sat on the edge of the bed, next to his shirts.

“Have you packed?” he asked. “We should take an early train tomorrow.”

“I could tell you what I wrote.” She picked a stray hair from one of the shirts. He continued folding to demonstrate his new philosophy: coming clean only made you dirty. He had no interest in it. “I said that we won’t be coming to U.S. anytime soon.”

Читать дальше