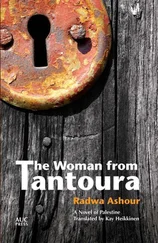

There were other files, of course, for similar cases from years before and after (1972, 1975, 1977 and so on), but I’m confining myself to the files from 1973 for the simple and practical reason that I got a photocopy of them from one of my comrades; the other reason is practical as well, namely that what I read in these files is a part of my own firsthand experience: the name Nada Abdel Qadir appears on three pages of the information gathered on her by the secret service in the dossier for the first case, and then the name recurs once again in the suspects’ statements, at the top of 25 pages recording statements she made thirty years ago in response to questions during the interrogations.

I leaf through the files, read parts of my comrades’ testimonies, skipping over other parts. I go back to what I’ve read before, read the dossier on Siham’s interrogation, and then read it yet a second time — or a third, or a seventh — the same week, or a month or a year later, or years later.

‘She was arrested, on the basis of a tip from the secret service, on 3 January 1973, after she left the University Dormitories, Cairo University. She was interrogated by the office of public prosecution for national security through the public prosecutor, Mr. Suhaib Hafez, on Thursday at one-thirty in the secret service headquarters, and the interrogation lasted until eight o’clock in the evening. The interrogator asked her…’

Then, ‘On the morning of Saturday 6 January 1973 the public prosecutor — the interrogator — returned to the secret service headquarters to continue the interrogation of the student Siham Saadeddin Sabri…’

And again, ‘On Monday morning, 8 January 1973, at the secret service headquarters, Mr. Suhaib Hafez continued interrogating the student…’

The papers for the case consisted of dozens of pages documenting Siham’s statements in a period of twenty hours spread over three days, on each of which she was transported in one of the secret service cars, from Qanatir Prison to the site of the interrogation at Lazoughli. She sat before the interrogator and talked, after which they would shackle her wrists once more, and she would leave the building and the car would bring her back to the prison. She went and returned, went and returned, went and returned.

‘Yes,’ she says, ‘I took part in the resistance to oppression and to the role of the university administration and the student unions in terrorising the students rather than representing and protecting them.’

‘Yes, I participated in the sit-in. I participated in the march. I participated in the conference. I participated in the activities of the supporters of the Palestinian revolution. I participated in the call for establishing committees for the defence of democracy.’

‘Yes, in my articles I criticised the authorities for their repressive actions and unjust policy in addressing national concerns.’

She says, ‘On 26 December 1972, while I was at the College of Engineering, some students from the Law School came and told me that the student union was holding a conference there, and that any student expressing a dissenting opinion was accused of communism, and was at risk of being attacked with knives. And in fact four students were wounded and taken to hospital. No one was interrogated about that.’

She says, ‘On 27 December 1972 the student union and the organisation for Islamic youth in support of the government tore down the wall-journals in the Law School and threatened the students with knives. In response to this provocation the students gathered for a rally, and it was my responsibility to move the rally out of the College of Engineering quickly, to avoid a dangerous riot. I stood in front of the crowd of students and started shouting, “To the courtyard, to Gamal Abdel Nasser Hall!” As the group was leaving the College of Engineering, the group hostile to us was calling out slogans against us and breaking the wooden rods used for hanging the magazines in order to use them against us as clubs. I decided to stay at my college to confront them. They surrounded me and said, “Get out of here, you Communist! If you don’t get out, we’ll pick you up and carry you out and beat you up. We don’t want you to open your mouth at this college, ever.” I sat down on the ground and said, ‘This is my college, and I’m not leaving it, and I will speak. You want to beat me up, carry on.” ’

The students had begun heading down the stairs, and they found a girl, by herself, sitting on the ground surrounded by youths threatening her with clubs; they found themselves in an embarrassing position, and began to disperse. No one was interrogated about that.

The prosecutor general’s office made no investigation into the perpetration of various types of brutality, such as the beating of students with truncheons and chains, on the day of the 3 January demonstration.

No investigation was made into the matter of the knife one of them was carrying and using to threaten the students.

There was no investigation into the injuries suffered by dozens of students, who were carried by their classmates on to the main campus of the university. Some of them had head injuries, and some were bleeding; others were choking from the effects of the tear-gas bombs, and still others were unconscious.

The prosecutor’s office made no investigation into what the security officers did when they smashed cars and shattered their windows with huge clubs, so that afterwards they could accuse the students of causing unrest.

There was no investigation of what one of the security men did when he dragged a handicapped student behind him, yanking him sharply along; the student, unable to keep up with his rapid pace, tripped, stumbled, and fell on the ground, while, from behind, soldiers beat and kicked him, shoving him and trying to force him to stand up and run — he would get up and make the attempt, but, hampered by his condition, would fall down again, and the kicking would resume.

The prosecutor general’s office never made any investigation.

I read Siham’s testimony as if I were back in the 1970s, following in her footsteps. Having heard her once I had wanted to hear more from her. There were only three years’ difference in age between us. What? I said, ‘So it’s possible.’ If I hurried, I thought, maybe in three years I could be like her. A flood-tide of feelings; images, scenes, sounds, questions, all rise to the surface. A lump in the throat wells up, then goes away: pride, self-assurance. I know what it means to be innocent; the thought brings a smile to my lips. I’m no longer the girl I once was, but a mother trying to protect her little girl from a devouring world. ‘It did devour her,’ I murmur. What’s done is done. ‘It devoured her,’ I say again, ‘many times.’ A shudder overtakes me. My eye catches the words, ‘the aforementioned’, and I laugh. The phrase is conspicuously repeated in the procès-verbal, and in the reports of the secret service, as it is in the charges brought against Siham: a comment in a wall-journal, the composition of an article or communiqué, participation in a conference or a sit-in or a demonstration.

In imagination and in principle it seems that the references of the secret service and the public prosecutor to those quite ordinary student activities as suspicious behaviour — necessitating secret reports and denouncers and witnesses for the prosecution; the knock on the door at dawn, the police on duty all night; prisons with budgets, administrations, officers and guards; vast blue lorries transporting people from here to there and from there to here; prosecuting attorneys opening investigations and closing them, applying themselves minutely to their signatures, followed by the date (day-month-year), after long hours of interrogation — this is what is laughable. But I laugh only at the words, ‘the aforementioned.’ No sooner does my eye fall upon the words than I start laughing — laughter I am at pains to keep in check, but I quickly discover, as it escapes from me and rises to a raucous crescendo that I’m incapable of restraining it.

Читать дальше