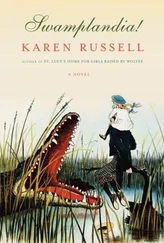

When I break free of the trees and make for the pond, my whole body primed for fight, there is no visible adversary to wrestle with. The Bellower is not the Bird Man. It’s not a wild gator. It’s my sister, standing stem-naked in the moonlight, her red skirts crumpled around her feet like dead leaves. Osceola, poised over dark water, and singing:

“Cluck! cluck! soul of So-and-so,

come and walk with me….”

On land, Ossie’s body looks like an unmade bed, lumpy and disheveled. But in the moonlight, my naked sister is lustrous, almost holy. This is a revelation to me, Ossie’s unclothed bulk, her breasts. My own chest is pancake-flat, and covered in tiny brown moles. All this time, my odd-waddling sister has been living in a mother’s body.

And something is shifting, something is happening to Ossie’s skin. As she walks towards the water, flying sparks come shivering out of her hair, off of her shoulders, a miniature hailstorm. It’s the lizards! I realize. She is shaking them off in a scaly shower, flakes of living armor. The geckos fall from her arms, her breasts, they plink into the pond, her hissing, viscous diamonds. I watch, mesmerized. Soon, my sister is completely naked, her thighs ruffled red by the high, prickly grasses. I don’t have enough breath left to say a word. And then, still holding the last note of her spell, Ossie walks into the water.

“Ossie, no!” Once I start screaming, I find that I can’t stop. But I don’t want to wade into the water until I can see exactly what morass I’m getting into. I feel around my overalls for the pocket flashlight, and find Seth’s eye instead, my lucky charm. With a biblical wail, I throw the eye at the back of her head.

“Osceola!”

This turns out to be a girly display of strength. The eye falls way short; it barely makes the pond. I picture Seth’s eye swirling down and settling in the red mud, its lidless gaze turned up towards Ossie as her legs twitch with the memory, the anticipation, of…what? I can’t make sense of what I’m seeing. All I know for certain is that she’s leaving me.

I wait for what feels like eons for Ossie to resurface, but the pond remains glassy and smooth, that same winking blankness of our mother’s mirror. Lily pads coagulate in blots of vapid light. Below the water, I sense more than see Ossie’s body, spiraling towards some mute blue crescendo.

“Don’t you dare!” I yell at the pond. “Don’t you dare go any farther down there!” I charge into the water after her.

I flail around in the shallows, black water pouring through my fingers, seeping into my eyes and mouth and ears, until finally my fingers brush skin. I seize Ossie’s shoulders and yank her up. The water buoys her huge body, and I swim with all my strength. No superhuman surge, or pony heroics; it’s just me at my most desperate. I splash towards the shore, making this anguished, honking noise, struggling to find purchase in the silty mud.

“Ava?” Ossie sputters. “What are you doing? Let me go!”

We fight each other with all the signature Bigtree moves — the whirligig, the chin thrust, the circumnavigator. Finally, with a triumphant howl, I manage to yank her onto the bank of the pond. I grab the fleshy pads of her feet, black as old orange peels, and try to drag her over a bed of rocks and sticks. Now Ossie is spitting up muck, and I can tell from her filmy, sightless rage that she is still possessed. A lily pad is pasted to her left cheek.

In the process of pulling her out of the water, I’ve dug these little half-moons into Ossie’s arm. Tiny nicks, like the violet impact of kisses, or bruises. They are already darkening, and I watch, fascinated, as they swell into puffy white welts. As if something were still clawing at her from within, pushing outwards, a pressure that is trying to break the skin.

My brother Wallow has been kicking around Gannon’s Boat Graveyard for more than an hour, too embarrassed to admit that he doesn’t see any ghosts. Instead, he slaps at the ocean with jilted fury. Curse words come piping out of his snorkel. He keeps pausing to readjust the diabolical goggles.

The diabolical goggles were designed for little girls. They are pink, with a floral snorkel attached to the side. They have scratchproof lenses and an adjustable band. Wallow says that we are going to use them to find our dead sister, Olivia.

My brother and I have been making midnight scavenging trips to Gannon’s all summer. It’s a watery junkyard, a place where people pay to abandon their old boats. Gannon, the grizzled, tattooed undertaker, tows wrecked ships into his marina. Battered sailboats and listing skiffs, yachts with stupid names— Knot at Work and Sail-la-Vie —the paint peeling from their puns. They sink beneath the water in slow increments, covered with rot and barnacles. Their masts jut out at weird angles. The marina is an open, easy grave to rob. We ride our bikes along the rock wall, coasting quietly past Gannon’s tin shack, and hop off at the derelict pier. Then we creep down to the ladder, jump onto the nearest boat, and loot.

It’s dubious booty. We mostly find stuff with no resale value: soggy flares and UHF radios, a one-eyed cat yowling on a dinghy. But the goggles are a first. We found them floating in a live-bait tank, deep in the cabin of La Calavera, a swamped Largo schooner. We’d pushed our way through a small hole in the prow. Inside, the cabin was rank and flooded. There was no bait living in that tank, just the goggles and a foamy liquid the color of root beer. I dared Wallow to put the goggles on and stick his head in it. I didn’t actually expect him to find anything; I just wanted to laugh at Wallow in the pink goggles, bobbing for diseases. But when he surfaced, tearing at the goggles, he told me that he’d seen the orange, unholy light of a fish ghost. Several, in fact, a school of ghoulish mullet.

“They looked just like regular baitfish, bro,” Wallow said. “Only deader.” I told my brother that I was familiar with the definition of a ghost. Not that I believed a word of it, you understand.

Now Wallow is trying the goggles out in the marina, to see if his vision extends beyond the tank. I’m dangling my legs over the edge of the pier, half expecting something to grab me and pull me under.

“Wallow! You see anything phantasmic yet?”

“Nothing,” he bubbles morosely through the snorkel. “I can’t see a thing.”

I’m not surprised. The water in the boat basin is a cloudy mess. But I’m impressed by Wallow’s one-armed doggy paddle.

Wallow shouldn’t be swimming at all. Last Thursday, he slipped on one of the banana peels that Granana leaves around the house. I know. I didn’t think it could happen outside of cartoons, either. Now his right arm is in a plaster cast, and in order to enter the water he has to hold it above his head. It looks like he’s riding an aquatic unicycle. That buoyancy, it’s unexpected. On land, Wallow’s a loutish kid. He bulldozes whatever gets in his path: baby strollers, widowers, me.

For brothers, Wallow and I look nothing alike. I’ve got Dad’s blond hair and blue eyes, his embraceably lanky physique. Olivia was equally Heartland, apple cheeks and unnervingly white teeth. Not Wallow. He’s got this dental affliction that gives him a tusky, warthog grin. He wears his hair in a greased pompadour and has a thick pelt of back hair. There’s no accounting for it. Dad jokes that our mom must have had dalliances with a Minotaur.

Wallow is not Wallow’s real name, of course. His real name is Waldo Swallow. Just like I’m Timothy Sparrow and Olivia was — is — Olivia Lark. Our parents used to be bird enthusiasts. That’s how they met: Dad spotted my mother on a bird-watching tour of the swamp, her beauty magnified by his 10x binoculars. Dad says that by the time he lowered them the spoonbills he’d been trying to see had scattered, and he was in love. When Wallow and I were very young, they used to take us on their creepy bird excursions, kayaking down island canals, spying on blue herons and coots. These days, they’re not enthusiastic about much, feathered or otherwise. They leave us with Granana for months at a time.

Читать дальше