“Wanna cut in, Ava?” She holds a hand to my forehead. “You okay?”

“Nah, s’okay. I mean, I’m okay. Maybe later.”

“Okay”—she frowns—“just let me know. Luscious doesn’t mind…. A-va!”

The music has stopped, without my noticing. I plunk in another quarter, scowling.

Soon, Patsy recommences, filling the straw room. Ugh. My sister has retreated to a dark corner, where she is nuzzling into the palm straw of the tiki wall. I chew on my pencil, unable to concentrate. I keep snapping up at every groove in the record, watching the windows for the Bird Man. He’s gone; I’m certain of it. I’ve scouted around, and there isn’t a single buzzard left in our mangrove forest. I haven’t figured out how to feel about this yet.

The next song is a slow dance. Ossie is struggling with her empty sleeves, trying to slip her own hand under her dress. I stop hearing the spaces between words, every song rising into an identical whine, bright and coppery, the wail of a jukebox banshee. My vision blurs. I’ll think I see the Bird Man’s face, his long fingers twittering against the glass, and then the panes go dark again. For a terrifying moment, the table melts into numbered squares, rows and columns, all blank.

DOWN

ACROSS

DOWN

ACROSS

Something is going wrong with my eyes, my forehead, my hot, stoppered throat, and I don’t know how to tell my sister.

What’s a six-letter word, the crossword asks me, for…

It is way past some kid’s bedtime when we finally leave the dance. My head is still pounding, but I’m not about to spoil Ossie’s good mood. She is flush with success, already nostalgic for the Swamp Prom. “Did you see those moves, Ava?” She keeps spinning beneath the giant cypress trees, starry-eyed, comparing Luscious to Fred Astaire. We hold hands on the walk home — Ossie’s fingers shooting out and linking through mine in the dark — and I feel a joy so intense that it makes my teeth ache inside my skull. It is everything I can do not to clamp down on Ossie’s hand, a gator wrestler’s reflex. We sing some silly songs from Ossie’s Boos! Spellbook, sloshing through the reeds:

I loose my shaft, I loose it and the moons cloud over,

I loose it, and the sun is extinguished.

I loose it, and the stars burn dim.

But it is not the sun, moon, and stars that I shoot at,

It is the stalk of the heart of that child of the congregation,

So-and-so.

Cluck! cluck! soul of So-and-so, come and walk with me.

Come and sit with me.

Come and sleep and share my pillow.

Cluck! cluck! soul.

The palmetto trees look like off-duty sentries, slouching together, gossiping pleasantly in the warm breezes. Fireflies wink on and off. The world feels cozy and round.

“Is Luscious coming home with us?”

“No,” Ossie says, unlocking the bungalow door. “He’s not going to come to Grandpa’s house anymore.”

I do my Flying-Squirrel Super Lunge onto my cot, burying my smile in the scratchy pillow. As I hear the door slam shut, I worry that I might start crying, or laughing hysterically. Just us, I grin, just us — just us! I don’t want to lie and feign regret, but neither do I want to hurt Ossie’s feelings by delighting in Luscious’s expulsion from her body. Instead, I make a noncommittal pillow sound: “Hrr-hh-mm!”

“Good night, Ava,” Ossie whispers. “Thanks for being the record player.”

When I wake up, my sister is not in her cot. Her shoes are gone. Her sheets are on the floor. The glass terrarium, the one Ossie dipped into as her personal jewelry box, usually opaque with lizards, has been ransacked. Only the water bottle and the decorative lichens remain.

“Ossie?”

In the closet, all of her hangers are naked as bones. When I check the bathroom, it’s like entering an invisible garden, perfumed with soap blossoms. The mirror is fogged up, and there is a note taped to the corner:

dir ava

i am not a bigtree enemore. i am living on my honey-moan. don worry we will com back and visat you. i will fid mom miself and brig her to. sory ava i haf the sownd of more words butt i coud not remember the shaps of the letters.

— ossie robacow

I have to read the letter three times before I understand that she’s left me for good. My judgment about these things is getting all the time better, and I know that this is not a secret for keeping. “Ossie, don’t go!” I holler. “Wait! I’ll…I’ll stove-pop you some Boos!” Which sounds wincingly inadequate, even to my own ears. What was the thing she was going to do? Eel-up? Earlobe? Elope, I remember. I find Grandpa’s dusty, checkerboard dictionary and check it for clues:

elope:[v] to run away, or escape privately, from the place or station to which one is bound by duty

Elope. The word lights up like a bare bulb, swinging long shadows through my brain. Because how exactly do you elope with a ghost? What if Luscious is taking my sister somewhere I can’t follow? What if she has to be a ghost, too, to get there? And then another horror occurs to me: What if it’s the Bird Man she’s been meeting all along?

You’d think I’d start after her right away, but I do not. I put on my rain boots, and then take them off, and then put them on again. I pick up the telephone to call for help, and then drop it back into the receiver, jumping at the blank hum of the dial tone. I try to scream, and only air comes out.

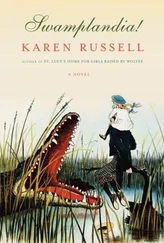

Outside, I can feel the swamp multiplying, a boundless, leafy darkness. The distant pines look like pale flames. Without the Chief to cordon it off, without the tourists to clap politely and commend it to memory, Swamplandia! has reverted to being a regular old wilderness. If the Bird Man were to show up right now, I would barrel into his arms, so grateful for the human company. Where is the Chief, I howl, and where is my sister? My hand hovers above the doorknob. I stand there, a thin wire of fear spooling in my gut, until I can’t stay in the empty house any longer. And I’d be tempted to tell Ms. Huerta that this is the feeling that separates us from the animals, if I hadn’t seen so many of the Chief’s dogs die of loneliness.

I pack a flashlight and a Wiffle bat and a steak knife and some peanut butter Boos, to lure Ossie back into her body. We don’t have any garlic bulbs, so I bring the cauliflower, and hope that any vampires I encounter will be of the myopic, easily duped variety. And then I open the door, and run.

The air hits me like a wall, hot and muggy. I run as far as the entrance to the stand of mangrove trees, and stop short. The ground sends out feelers, a vegetable panic. The longer I stand there, the more impossible movement seems.

And then comes that familiar sound, that raw bellow, pulsing out of the swamp.

The cubed thing inside me melts into a sudden lick of fear. Something hot-blooded and bad is happening to my sister out there, I am sure of it. And the next thing I know I am on the other side of the trees, crashing towards the fishpond. It’s a sensory blur, all jumps and stumbles — oily sinkholes, buried stumps, salt nettles tearing at my flesh. I run for what feels like a very long time. One wisp of cloud blows out the moon.

I wish I could say I gulp pure courage as I run, like those brave little girls you read about in stories, the ones who partner up with detective cats. But this burst of speed comes from an older adrenaline, some limbic other. Not courage, but a deeper terror. I don’t want to be left alone. And I am ready to defend Ossie against whatever monster I encounter, ghosts or men or ancient lizards, and save her for myself.

Читать дальше