The G up high, then C, down to E b, C, A b, double bar for the suspended fourth, watch the third finger. Shuffle on C, suspended on the F, down to C, B b, G, chorus.

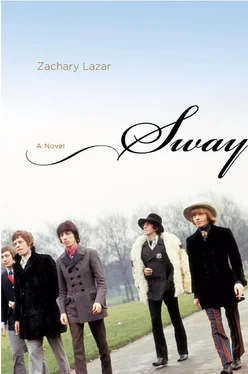

Across from him, Keith sat with his head slumped over on his shoulder, his eyes half-closed. He hadn’t been to bed in two days — no rehearsals, just a long binge that still hadn’t stopped. He remembered Anita passing him the joint after they’d taken in the news about Brian, then the long drive to London, dropping her at the flat in Chelsea, then two days later — this morning — walking across this same park a little after five o’clock. He wasn’t going to stop. He didn’t know if he was strong enough to survive the kind of life he was going to try to survive, but it was who he was. Every day he was more certain of that. Anita was eight and a half months pregnant with their child. She was out there somewhere in the crowd now with Marianne, the two of them sitting in the sun, getting high. A part of him was distracted, angry, as if Brian were still alive. The band had not played in front of a live audience in three years, and now Brian had just died, making it even harder.

Mick was sitting with his hands in his lap and looking straight ahead at nothing. He had a summer cold. His throat was so sore that he could hardly speak, much less sing, but he was purposeful in the way of someone who knew he couldn’t fail. He was going to walk onstage in front of half a million people, and to do this was like walking onstage naked. It was an act of surrender that had to look and feel like an act of conquest. His sign was Leo, the sign of Strength in the tarot deck. Its glyph looked like an omega, the sign of infinity, or of the apocalypse, depending on whom you asked. The band’s support staff had a code name for today’s events. They were calling it the Battle of the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

Memories of the riots outside the Democratic convention in Chicago, the riots in Paris, the riots in Berkeley. The crowd was getting high and doing crossword puzzles, and a few of them were playing guitars, and they didn’t know what to feel about the sight of the armored van moving up the path through the crowd. Its way was cleared by six motorcyclists in spiked helmets and leather jackets, an imperial guard armed with beer cans and knives. The words “peace” and “love” had been used so many times by now that they meant almost anything, including their opposites. It was what gave the words their charge. It was why some of the men in the crowd were wearing olive drab fatigue jackets, like GIs in Vietnam.

Tom Keylock announced over the P.A.: “Ladies and gentlemen, the world’s greatest rock-and-roll band.”

A subdued kind of cheering started. They whistled and shouted encouragement and then they stood up to take in the view and then the applause thickened into a diffuse cloud of noise.

Anita stood up with them. Her eyes closed and her smile loosened into something dreamy and approving as Marianne pulled her back gradually into her arms, all four of their hands on her pregnant belly. Anita wore black kohl on her eyes and a purple gypsy dress and a crown of Moroccan coins around her straw-colored hair. Apart from her belly, she hardly looked pregnant at all. As Anger filmed her, he was struck once again by how much she looked like Brian.

They were the world’s greatest rock-and-roll band. Even a year ago, no one would have made such a claim, but now it seemed obvious. They had a backlog of more than two hundred songs. Country songs, blues songs, rock-and-roll songs. Mick and Keith didn’t know where they came from, only that the flow had been unstoppable in the last year or so. During that time, Keith had taught himself to play the guitar in several different tunings, the notes all in different places on the fretboard, moving from one accident to the next, everything working. They’d written riot songs, war songs, murder songs, drug songs, and these had turned out to be exactly the songs people wanted to hear. It was toilet music, dirt music, the music of 1969.

From his place on the scaffolding, Anger considered stopping the film. Mick had come onstage alone, and he looked all wrong — he looked lost. His long hair fell into his eyes like a sheepdog’s and he wore a gauzy white gown and black lipstick. He had a large, solemn-looking book in his hand, possibly the Bible, and there was something priestly about him as he tried to quiet down the crowd.

“Now listen,” he said. “Cool it for a moment.”

Behind him, there was a large cardboard cutout of Brian, standing in the sunlight like a figure on the wall of a temple. He wore a fur coat and half a dozen brightly colored scarves, making the Hindu greeting of two palms pressed together before his chest.

Mick read something archaic and strange. He read it in a prim, unconvincing voice that made it sound as if he didn’t know or even care what the words meant.

The One remains, the many change and pass;

Heaven’s light forever shines, Earth’s shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments. — Die,

If thou wouldst be with that which thou dost seek!

Follow where all is fled! — Rome’s azure sky,

Flowers, ruins, statues, music, words, are weak

The glory they transfuse with fitting truth to speak.

To the crowd, it maybe sounded like Shakespeare. Anger recognized it as Shelley’s Adonais . But what did Mick mean when he ordered them all to die? Did he mean that Brian had found some “white radiance of Eternity,” or did he mean nothing at all? Mick was the Prince of Darkness or the Angel of Light. It was difficult to say why he was so hard to stop looking at.

Keith sniffed from his canister, once for each nostril, then let the silver straw dangle down from the chain he wore around his neck. He picked up his guitar and slung it over his back as the crew flung open the doors of two large boxes at the front of the stage. They were full of butterflies — moths — and they flickered for a few moments in a daze above the crowd, half-suffocated, then wafted down like white confetti on the massed heads and the black-painted stage.

The Hells Angels leaned back against the iron barricades, legs crossed, passing each other beers. The band tuned its guitars. The cardboard cutout of Brian smiled unchangingly at the crowd, a billboard advertisement for a children’s play about a magic prince.

It started with a flat, basic drumbeat, so slow that the song felt as though it was about to collapse before it even started. Mick was trying to move in time, a half jog, half chicken walk, wading through thick sludge. He’d taken off his white gown and was wearing tight cotton pants and a sleeveless mauve T-shirt. Keith didn’t look at him. His guitar part was one chord, so useless that he didn’t even face the crowd but stared down at his strings, as if waiting for something better to happen. Mick stared at him: it was too slow. He was almost ready to give up and start over. He clapped his hands and waved his head from one side to the other, a rueful smile on his face, but then Keith finally got to the first riff, a major-key country riff slowed down to one-quarter speed. He mangled a few double-stops in the middle, but now it started to make sense. The point of the song was its big gaping holes, the ragged dead spaces between the sounds. It was always about to break down, a half step behind. The drums leveled out at the same slack pace. Keith leaned back, head nodding, then stepped forward on one long leg, a black-haired ghost in bullfighter’s pants, a crescent moon dangling from his ear.

It was the band’s new sound. Mick put his hands in his hair and pouted and stood on his tiptoes. For a moment, he looked like a street drunk yelling denunciations at strangers. His first words were incomprehensible, but it didn’t matter. They were all looking at him now. He scowled and pointed his finger, then mouthed a kiss: a dictator for half a second, then a dancer out of Swan Lake.

Читать дальше