One night there was a party. Brian was swimming, the latest girlfriend was swimming. Everyone had been drinking, taking pills, diving off the low board into the blue-lit pool. The workers were there — they were swimming too, in borrowed trunks. One of them splashed water in Brian’s face. He didn’t retaliate. Perhaps that was the reason it didn’t stop, because he just wiped his eyes and shook his head a few times. Someone dunked him underwater a few minutes later. After that, there was a lot of splashing. The girlfriend turned and saw it from the porch: a thrashing in the water, the swirling blue surface broken at one end. She turned and continued toward the house, looking for cigarettes. When she came back out, they were all standing around the pool except for Brian, who at first looked like just a shadow beneath the surface of the water.

No one ever said what happened. He was a strong swimmer, there were plenty of people there with him. Either they drowned him or they let him drown.

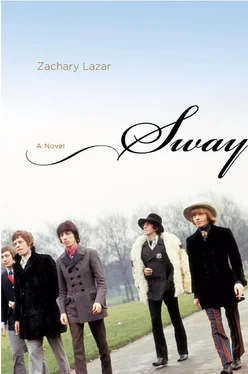

IT WAS JULY 5.In the center of London, in Hyde Park, five hundred thousand people were waiting for the band to arrive in his honor. The past year had already been full of vivid catastrophes: the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the Soviet invasion of Prague, half a million troops in Vietnam, the Cuyahoga River going up in flames. Now Brian had died, and half a million people were spread out from a large black stage with towers of black scaffolding to make a dense rectangle of tiny flesh-colored blips, mostly faces and hair. They wore the somber, utilitarian clothes of that year: jeans, work boots, leather sandals, sunglasses. They were a peaceful crowd, but there was a familiar playfulness that was missing. It was a warm day and some of the men had taken off their shirts, but there were very few flowers or beads or Indian-style pajamas. They were thoughtful, unsmiling, squinting in the sunlight, shading themselves with sheets of newspaper. There was no visible grass in the park, only people and trees, cut through at the center by the silver water of the Serpentine.

You wanted to be there, but once you saw how many people were there you began to feel a little strange about being a part of something so ambiguous. It was hard to know what to feel — a beautiful day in July, very sunny, the trees in full leaf. It made it worse somehow that Brian had died in such a stupid way. You wondered, were you there to celebrate or to mourn or what? And what were you celebrating or mourning?

No one knew what to make of the set of iron barricades that had been set up about fifteen yards from the stage. It enclosed the press seats and the seats for special guests and friends of the band. Patrolling these barriers was a squad of two dozen young men in studded leather jackets and leather gestapo caps, members of the London chapter of the Hells Angels. Their motorcycles were lined up on the sides of the stage, all the front wheels turned to the same angle. They never stopped scanning the seated crowd, never stopped convening with one another in little groups. The crowd never stopped pretending that they weren’t there.

From a tower of scaffolding to the left of the stage, Anger was filming it all on his Kodak Cine Special camera, a gaunt man in black pants, hair wafting in the breeze. He thought that at least a few of the fans would get up and dance to the music on the P.A., even climb up for a quick frolic on the empty black stage, but none of them did. There was the hush and awe of hierarchy. It occurred to him that his time with the band would be in jeopardy now, that they would have less and less time for people like him. After today, their circle would just get narrower and narrower. They would be as remote as pharaohs or Hollywood stars. He saw that the Hells Angels were more than just a defensive force, they were also the embodiment of some punitive urge the crowd had, an urge to atone.

Brian Jones, 27, was found dead in his swimming pool Thursday, apparently the result of drug and alcohol intoxication. A spokesman for the band says that they have decided to carry through with their plans to host the free concert this afternoon in Hyde Park as a tribute to his memory. Jones was the band’s founding member. Last month, after a series of drugs arrests, he announced that he was leaving the group over musical differences.

He had tried not to push too hard, staying in the background, not a participant but an onlooker. An invisible nimbus seemed to surround them sometimes, a kind of electrical field that made them hyperrealistic, unapproachable. They were stars — lights that were out of reach — and he had tried to understand this. But it had been six years since he’d made a new film. He could feel it like a pressure in his lungs, the images impacted, jostled together, superimposed. The smallest effort on their parts would make all the difference.

The crowd before him was religiously large, a kind of death cult in the new Aquarian style. It had little chance of being much else in these years of violence, riots, assassinations, Vietnam. A rock star drowned in his swimming pool. A gunman appeared in a crowd to murder a president, a senator, Martin Luther King, and in the process somehow became infused with the romance of the person he’d killed. It was the logic of thanatomania, not a sequence of cause and effect but an underlying current, a unifying style. With each death, the mystery of death took on more and more glamour, the romance making the human world feel less and less bound to the earth.

He remembered a dream Anita had told him about just a few months ago, at Keith’s country house. In the dream, she was in the desert in California, walking on the sand beneath a cloudless blue sky, when suddenly she’d lost her sense of hearing. There was no sound. She knew then — though there was no mushroom cloud, none of the obvious signs — that the world had ended. At that same instant, hundreds of dragonflies appeared in the air, all of them flying in the same direction. Their bodies seemed to be made of glass, a glistening blue, as if she could see the sky through their transparent shells.

“It went on for a long time,” she said. “It was like if I kept walking, everyone might still be where they were supposed to be and we’d all just go back to the way we were before. Only I knew it wasn’t true. I knew everything had changed. There was just this endless little moment where I didn’t have to face what had really happened yet.”

Anger had looked down at his hands, thinking even then that in some way the dream was about Brian. The three of them were sitting on some Moroccan carpets spread out on the grass, and when he looked back up, the different planes of Anita’s and Keith’s faces were flashing orange or black in the lantern light like fun-house ghouls.

“A dream of heaven,” he’d said, meaning timelessness, uncertainty, unknowing. But Anita had looked down at her hand on her knee, not liking the word.

“It wasn’t like that,” she said. “It wasn’t like anything I’ve ever thought about before. It was strange. I don’t know where something like that comes from.”

Keith brought his dangled hand to the collar of her leather coat. She looked up at Anger, her face angular and lean, a face out of Dürer. Then Keith leaned forward slightly, offering him the end of a joint.

“People always think the world is coming to an end,” Keith said. “But it never does. They wish it would end sometimes because they can’t control it. But you never control it. All you can do is react.”

They were crammed into an armored car, a dark container with bench seats that inched its way up the narrow park road through the crowd. Their journey from the Londonderry Hotel to the stage in Hyde Park was less than a quarter of a mile, but it would take them almost forty-five minutes. Their new guitarist, also named Mick — Little Mick — was staring down at the floor as the van shunted from side to side, jostling his body. He was nineteen years old, a wiry-haired boy in a kind of swashbuckler’s shirt with puffy sleeves and a set of crossed laces at the collar. He had been in the band for less than three weeks and had never played with them anywhere but in Keith’s basement.

Читать дальше