Oja dragged him away from his father and looked at him severely. ‘Tell me the truth,’ she said. ‘Did you read the whole story?’

Adi made a tired face at his father, pleading for rescue with his large eyes, and said, ‘Yes, I read it’.

‘So fast?’

‘Yes.’

‘What happens in the end?’

‘There are many stories. Which end do you want?’

‘What happens in the end of the end?’

‘Don’t confuse me.’

‘Tell me, Adi, what happens in the end of the last story.’

Adi took off his hearing-aid and shut his good ear with one finger.

‘Adi,’ his mother screamed, stuffing the hearing-aid back into his ear, ‘What happens in the end of the last story?’

‘The giant runs away.’

Oja checked the last page of Tinkle. ‘There is no giant,’ she said. ‘Did you read this book? Tell me the truth. You should never lie, Adi. The end of an ox is beef, the end of a lie is grief.’

‘So what if he does not want to read silly comics,’ Ayyan said, winking at his son who winked back.

‘You don’t interfere,’ she said angrily. ‘This boy is going to become mad if I don’t do something about it right now. Yesterday, he was standing alone on the terrace, in a corner. Other boys were playing.’

Adi put his hand on his head in exasperation. ‘You don’t understand,’ he said. ‘How many times do I have to tell you? I was out.’

‘What do you mean, you were out?’

‘I was in the batting team and I got out.’

‘So?’

‘If you get out, you can’t bat till the next match.’

‘But other boys were playing,’ she said.

‘Don’t confuse me,’ Adi said angrily.

‘Look, Oja,’ Ayyan said sternly, ‘when a batsman gets out, his chance is over. He cannot play.’

‘Why are you always on his side?’ she said. ‘And why are you standing here? The meeting is going on now. You are late.’

‘I’ll go, I’ll go.’

The television was on all this while. Oja now appeared to calm down and she settled on the floor to watch her soap. Ayyan observed her closely. He knew something was wrong. Her eyes had been shifting too often towards the washing machine and even now she was not in the trance she usually was while watching TV. She seemed to be very aware of him. She looked sideways to see where he was.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

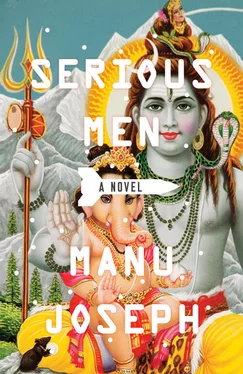

‘Nothing,’ she said, and stole another glance at the washing machine. Ayyan opened its lid and peered in. There was a red cardboard box inside. Oja said, first softly and then with a rising pitch, ‘What’s wrong with having a god? All these people have a real god in their homes.’ Ayyan opened the box and there he was — a cheerful Ganesha. It was not the first time she had brought the idol of the elephant god home. Ayyan always threw him away on his way to work. But every few months, the lord returned in different moods.

Ayyan rolled the idol in a newspaper. ‘I will throw him somewhere tomorrow,’ he said.

‘You cannot keep doing that,’ Oja screamed. Adi took off his hearing-aid and shut his right ear.

‘Isn’t Buddha enough?’ Ayyan screamed back. ‘Buddha is our god. The other gods are gods the Brahmins created. In their deviant stories, those gods fought against demons which were us. Those black demons were our forefathers.’

‘I don’t care what the Brahmins did. Their gods are now mine,’ Oja said. Her voice faltered. ‘I am a Hindu. We are all Hindus. Why do we pretend?’

‘We are not Hindus, Oja,’ he said, now calm and somewhat sad. ‘Ambedkar liberated us from being treated like pigs. He showed us how to renounce that cruel religion. We are Buddhists now.’

‘I can live with nothing,’ she mumbled, ‘I don’t even want dreams. All I am asking is to let me have some gods. Our son is growing up. I want him to know the gods that other boys know. I want to take him to the temple. I want him to be aware of these things. I want real festivals in this house.’

Ayyan considered what his wife had just told him about their son. He had thought about it before. In a way, Adi was growing up like an animal, without any influence of culture. The epics that his father believed were the propaganda of the Brahmins were also the only epics the boy had. And a boy needed those to understand fully that there was an eternal battle between good and evil, and that in an ideal world the virtuous triumphed over the bad. Superman was good, but Mahabharata was deeper. It had complexity. It made the good choose the wrong path, and there were demons who were fundamentally nice persons, and there were gods who ravished bathing girls. Ayyan wanted his son to know those stories. Even though he could not accept Hindu idols in his home, for some time now he secretly wished Oja would win that battle. He wanted to yield but yield grudgingly, so that the religion of the upper castes could be used in his home for entertainment and education, and nothing more. He wanted Adi to grow up knowing morals, patriotism and the gods. And when the boy turned twenty, may he have the intelligence to abandon them all.

Oja wiped her tears and looked angrily at her husband. The way she looked, he knew what she was going to say.

‘His ear,’ she said, and wept, pressing her wrists on her eyes, ‘This might not have happened if we had had gods.’

‘Enough,’ Ayyan screamed.

There was a time when Ayyan thought he might never become a father. Long before he had married Oja, he had once gone to a fertility clinic’s nascent sperm bank with the insane idea of donating his Dalit semen to the fair childless Brahmin couples. He had heard that sperm banks do not reveal the identity of the donor, and so his seed could impregnate hundreds of unsuspecting high-caste women. He hoped stout brooding Dalits would spring up everywhere. But the doctors there told him that he had a defect and so his contribution could not be accepted. His sperm-count, they said, was just half the normal rate.

He told Oja about the defect many months after their marriage. ‘Since my sperm-count is half the normal rate, you must be doubly prepared to sleep with me,’ he had said. She replied in a lethargic way, in the middle of folding clothes, ‘I don’t understand all this maths.’ Despite his fears, just three years after their marriage, Adi was born. In the insanity of her labour, Ayyan will always remember that Oja had screamed the filthiest abuse at him. He didn’t know any woman could mouth such words, let alone his wife. ‘My husband is a son of a whore. May his arse explode,’ she had screamed in Tamil. But it was a tradition. Women in her tribe had to abuse their men when they were in labour.

As Adi grew up, they slowly learnt that he was almost entirely deaf in his left ear. Oja believed that the gods were angry. Buddha’s eternal smile, she had always interpreted as the peace of a cosmically powerless man. It was the other gods, the Hindu gods, who had all the magic. One night, she told her husband with a wisdom that baffled him, ‘You love this man who found God under a Peepal tree. Do you know that a Peepal tree is a Brahmin? Yes it is.’

Ayyan could never bear it when he saw Oja cry. His heart grew heavy at the sight and his throat felt cold. He thought of what he could say about the elephant god whom he would fling by the wayside tomorrow. He searched for something entertaining. ‘You know, Oja,’ he said, ‘an elephant’s trunk has four thousand muscles.’

There was a time when she used to love such facts. She would marvel at a world that was so strange and at her man who knew so much. He collected such curious facts every day to ration them out to her.

‘Did you know elephants can swim?’ he tried again. ‘Five years ago, a whole herd of elephants swam three hundred kilometres to reach a far island. Can you imagine? Thirty of them swimming three hundred kilometres. Their fat legs pedalling underwater.’

Читать дальше