Only at home did the world open out for Claire, spread its toes to dig down into the cool infinite. She loved to sit with her head uncovered, to feel the air move against her scalp, to be attuned to the exact moment a sunbeam touched her forehead, something that in her un-stripped-down state she had been oblivious to. It occurred to her, as dispassionately as watching a cloud cross the sky, that this deep joy she felt in the ordinary might be a prelude to her death.

In her more optimistic moments, she did not believe that the cancer would kill her, but she did feel privy to a great secret that changed everything else: namely, that someday, sooner or later, something would. This was the kind of impossible knowledge that one pays lip service to, but it was like explaining the feeling of being in love, or the pangs of childbirth, or the ache of fear or loneliness. One can only know such things from the inside out.

* * *

After a difficult night during which Claire hardly slept, Minna and she walked through the orchards earlier than usual, the tule fog dense as ever. Claire, bald-headed, dressed in a clownish, marigold-colored robe given to her by Mrs. Girbaldi, thought she must appear like a supplicant Buddhist nun.

“I hate the nights,” Claire said.

“I am always happiest in mornings and afternoons, never at night,” Minna said. “Ghosts haunt one then.” Suddenly Minna veered off and headed to an area that Claire had been careful to avoid. She dragged behind, trying to think of excuses not to continue.

“We’ve never walked here,” Minna said.

“Nothing of interest.” Claire stopped at the place the asphalt road gave out, but Minna insisted on walking down the gravel path.

The asphalt road faltered, crumbled into large bits of rock and gravel, further broke down to sand, then scraped into raw dirt and rough clay. Ants colonized part of the gully, and electric-blue thistle flowers crowded an uprooted eucalyptus, out of whose roots wild willow smothered the path leading to the wash.

Claire was torn between following and returning alone to the house when she heard Minna’s cry. Reluctantly she approached. Minna stood stricken in the clearing as if she had seen a gravestone. Claire coughed, ready to come up with some fatuous story, but Minna waved her off. She waded through the bracken and undergrowth, lush from neglect.

Claire had not visited the tree in years, and Octavio avoided cultivating a large area around it until it had become enchanted in its abandonment.

“We should be getting back,” Claire said quietly and futilely. With no sign Minna had heard her, exhausted, she sat on the ground, her back to Minna and the tree. “I’m feeling bad, if you care,” she shouted.

No response. Claire turned just in time to see Minna place her hand against the trunk, as if taking its heartbeat, as if searching for clues inside for the sad state of abuse on the outside.

“Minna!” Claire yelled, but the words pushed back down her throat. She closed her eyes and must have dozed off because she woke blinded and overheated by the sun. Minna glared down at her, eyes bleared, swollen. She knelt and with an outspread hand touched Claire as she had touched the tree, and Claire shrank away as if she were being branded with a bloody imprint.

“This is the God wood,” Minna said. “The tree of good and evil. Your tree of forgetting.”

“I don’t want this.”

“Pauvre amie . This is where it happened. A son who died here.”

“We don’t talk of it,” Claire whispered, as if their words might bring down the sky.

Minna’s eyes were bright with excitement. “This is why you stay.”

Claire turned away, aware now of footsteps and the sound of low voices. Five of the workers stood at the head of the road with their pruning tools, ready to begin the day. Like thieves, Claire and Minna stood and stumbled past them, Claire whispering, “Buenos dias” and “Discúlpeme,” covering her poor, exposed head with one hand.

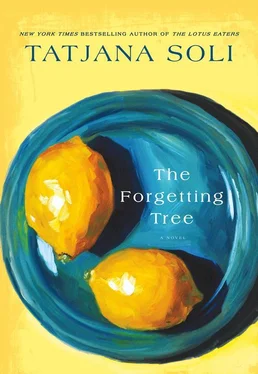

When they reached the house, Minna pulled two lemons from her pocket. One lemon was rounded, with a deep cleft running through it so that it was like a crenellated heart, or perhaps two lemons that grew into each other’s space and conjoined. The other was blackened and hollow, a victim of hanging unpicked from the previous years.

“What are you doing?” Claire asked, horrified by the sight.

Minna shrugged.

“You can’t bring those in the house.”

“It’s only fruit.”

“Get rid of them.” Claire was enraged that Minna would defile the tree, disinterring the fruit, and at the same time shamed at her own irrational reaction. “How did you know?”

“Places are marked by what happened there. Sometimes they are cursed by bad luck, sometimes they become sacred, but either way they are marked.”

They did not speak for the rest of the afternoon. On schedule, the tule fogs rolled back in at sunset and blanketed the hot fields, cooled over Claire’s temper. They pretended, unsuccessfully, the blaze of the day and its events had never been.

Syringes of Adriamycin the deep color of cherries or blood. Claire dreamed in red and woke with dry heaves. Methotrexate the deep yellow of egg yolks. Whole cocktails of medicines — mix the Taxol with the cisplatin, shake the Cytoxan with the fluorouracil. Face reddened and bloated, chest and arms rashed.

She woke with the conviction, like a toothache, that if she went in for her treatment that day, she would be weakened beyond the point of recovery. She picked up the phone and called Mrs. Girbaldi.

“Nan, tell me about that clinic.…”

Minna came into her bedroom, busy, hardly looking at her as she laid out Claire’s clothes and went back out. She was talking about saints and symbols she had looked up in a book to paint on her walls, walls that had long ago been filled. “Coming for breakfast, your ladyship?” Claire heard the slap of her bare feet down the hall and was still under the covers when she returned.

“Come on, sleepyhead.”

“I’m not going today.”

Minna stopped. “It’s not an either/or proposition.”

“I’m serious. I can’t do it today.”

“I’ll have to call the doctor. I’ll have to call Gwen.…”

“Please.”

“It’s my responsibility . My job . It’s your life we’re talking about, doudou . I would be negligent.”

“If I go today, it’ll kill me.”

“What if they don’t believe me…”

“You believe me,” Claire wheedled, grabbed Minna’s hand. The girls had pulled similar stunts when they were little, and she never once gave in. But she knew Minna was inexperienced. Claire schemed she could trade on Minna’s changeable heart.

Minna hesitated, stroked Claire’s hair. “I’ll say we had car trouble. I’ll reschedule.”

“Not this week.”

“Don’t be greedy.” Minna stood thinking. “Get dressed for breakfast before I change my mind.”

They sat in the kitchen. Claire obediently stirred syrup into her oatmeal, drank her coffee, and poured more.

“I want to try a clinic in Mexico Mrs. Girbaldi told me about.”

“What’s going on with you?”

Claire sagged down into her chair. “I’m starting to forget what I’m living for. I want to go away somewhere exotic and forget … this.”

“Oh, che, exotic is on the inside. Back home, we sat around bored to death with all the green of the jungle, all the blue of the ocean. Each last one of us would have cut off our right arm to be in California.”

“But you could have left at any time.”

Minna drank her coffee. “Someday I will take you. A place very far, with steep mountains and waterfalls. Where the flowers open only at night. Their perfume is so strong you forget all the pain in your life.”

Читать дальше