It was only then that I realized why. It wasn’t the chick she’d hoped it would be, perhaps. Its leg was twisted, and its three claws were just a stump. Back then I hadn’t yet learned what all of you know: that animals kill their young when they’re born different. Why do pumas claw their cubs that are lame or one-eyed? Who do sparrow hawks tear their young to pieces if they have a broken wing? They must sense, since the life of young such as that is not perfect, it will be difficult, with much suffering. They won’t know how to defend themselves, to fly, or hunt, or flee, or how to fulfill their obligation. They must sense that they won’t live long, for other animals will soon eat them. “That’s why I’ll eat it myself, so that it feeds me at least,” they perhaps tell themselves. Or could it be that, like Machiguengas, they refuse to accept imperfection? Do they, too, believe that imperfect offspring were breathed out by Kientibakori? Who knows?

That’s the story of the little parrot. He’s always curled up on my shoulder, like this. What do I care if he’s not pure, if he’s got a game leg and limps, if he flies even this high he’ll fall? Because, besides his stump of a foot, his wings turned out to be too short, it seems. Am I perfect? Since we’re alike, we get on well together and keep each other company. He travels on this shoulder, and every now and then, to amuse himself, he climbs up over my head and settles on the other shoulder. He goes and comes, comes and goes. He clings to my hair when he’s climbing, pulling it as though to warn me: “Be careful or I’ll fall; be careful or you’ll have to pick me up off the ground.” He weighs nothing; I don’t feel him. He sleeps here, inside my cushma. Since I can’t call him father or kinsman or Tasurinchi, I call him by a name I invented for him. A parrot noise. Let’s hear you imitate it. Let’s wake him up; let’s call him. He’s learned it and repeats it very well: Mas-ca-ri-ta, Mas-ca-ri-ta, Mas-ca-ri-ta…

Florentines are famous, in Italy, for their arrogance and for their hatred of the tourists that inundate them, each summer, like an Amazonian river. At the moment, it is hard to determine whether this is true, since there are virtually no natives left in Firenze. They have been leaving, little by little, as the temperature rose, the evening breeze stopped blowing, the waters of the Arno dwindled to a trickle, and mosquitoes took over the city. They are veritable flying hordes that successfully resist repellents and insecticides and gorge on their victims’ blood day and night, particularly in museums. Are the zanzare of Firenze the totem animals, the guardian angels of Leonardos, Cellinis, Botticellis, Filippo Lippis, Fra Angelicos? It would seem so. Because it is while contemplating their statues, frescoes, and paintings that I have gotten most of the bites that have raised lumps on my arms and legs neither more nor less ugly than the ones I’ve gotten every time I’ve visited the Peruvian jungle.

Or are mosquitoes the weapon that the absent Florentines resort to in an attempt to put their detested invaders to flight? In any case, it’s a hopeless battle. Neither insects nor heat nor anything else in this world would serve to stave off the invasion of the multitudes. Is it merely its paintings, its palaces, the stones of its labyrinthine old quarter that draw us myriads of foreigners to Firenze like a magnet, despite the discomforts of the summer season? Or is it the odd combination of fanaticism and license, piety and cruelty, spirituality and sensual refinement, political corruption and intellectual daring, of its past that holds us in its sway in this stifling city deserted by its inhabitants?

Over the last two months, everything has gradually been closing: the shops, the laundries, the uncomfortable Bibliotèca Nazionale alongside the river, the movie theaters that were my refuge at night, and, finally, the cafés where I went to read Dante and Machiavelli and think about Mascarita and the Machiguengas of the headwaters of the Alto Urubamba and the Madre de Dios. The first to close was the charming Caffè Strozzi, with its Art Deco furniture and interior, and air-conditioning besides, making it a marvelous oasis on scorching afternoons; then the next to close was the Caffè Paszkowski, where, though drenched with sweat, one could be by oneself, on its time-hallowed, démodé upstairs floor, with its leather easy chairs and blood-red velvet drapes; then after that the Caffè Gillio; and last of all, the one that was in all the guidebooks and always jammed, the Caffè Rivoire, in the Piazza della Signoria, where a Caffè macchiato cost me as much as an entire meal in a neighborhood trattoria. Since it is not even remotely possible to read or write in a gelateria or a pizzeria (the few hospitable enclaves still open), I have had to resign myself to reading in my pensione in the Borgo dei Santi Apostoli, sweating profusely in the sickly light of a lamp seemingly designed to make reading arduous or to condemn the stubborn reader to premature blindness. These are inconveniences which, as the terrible little monk of San Marcos would have said (the unexpected consequence of my stay in Firenze has been the discovery, thanks to his biographer Rodolfo Ridolfi, that the much maligned Savonarola was, all in all, an interesting figure, one better, perhaps, than those who burned him at the stake), favorably predispose the spirit toward understanding better, to the point of virtually experiencing them personally, the Dantesque tortures of the infernal pilgrimage; or to reflecting, with due calm, upon the terrifying conclusions concerning the cities of men and the government of their affairs drawn by Machiavelli, the icy analyst of the history of this republic, from his experiences as one of its functionaries.

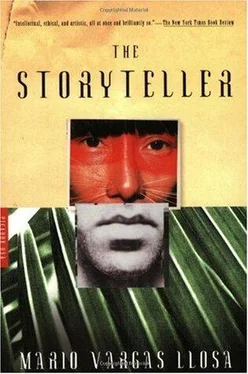

The little gallery in the Via Santa Margherita, between an optician’s shop and a grocery store and directly opposite the so-called Church of Dante, where Gabriele Malfatti’s Machiguenga photographs were being shown, has also shut, of course. But I managed to see them several times more before its chiusura estivale. The third time she saw me come in, the thin girl in glasses who was in charge of the gallery informed me that she had a fidanzato. I was obliged to assure her in my bad Italian that my interest in the exhibition had no ulterior personal motives, that it was more or less patriotic; it had nothing to do with her beauty, only with Malfatti’s photographs. She never quite believed that I spent such a long time peering at them out of sheer homesickness for my native land. And why especially the one of the group of Indians sitting in a sort of lotus position, listening, enthralled, to that gesticulating man? I am sure she never took my assertions seriously when I declared that the photograph was a consummate masterpiece, something to be savored slowly, the way one contemplates The Allegory of Spring or The Battle of San Remo in the Uffizi. But at last, after seeing me four or five times in the deserted gallery, she was a little less mistrustful of me, and one day she even permitted herself a friendly overture, informing me that an “Inca combo” played Peruvian music on traditional instruments every night in front of the Church of San Lorenzo: why didn’t I go see them; they would bring back memories of my homeland. (I obeyed, I went, and I discovered that the Incas were two Bolivians and two Portuguese from Rome who were trying out an incompatible synthesis of Portuguese fados and Santa Cruz carnival music.) The Santa Margherita gallery closed a week ago and the thin girl in glasses is now spending her vacation in Ancona, with her parents.

Читать дальше