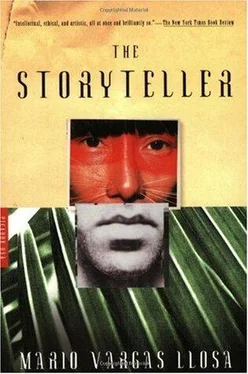

Mario Vargas Llosa - The Storyteller

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mario Vargas Llosa - The Storyteller» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, Издательство: Picador, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Storyteller

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Storyteller: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Storyteller»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Storyteller — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Storyteller», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The second day, all of a sudden, they left. The parrots flew off in terror. All at the same time, squawking, shedding feathers, flying into each other, as though an enemy were approaching. They’d smelled danger, it seems. Because just then, right over my head, leaping from branch to branch, there came a talking monkey, a yaniri. Yes, the very same, the big red howling monkey, the yaniri. Enormous, noisy, surrounded by his band of females. Leaping and swinging all around him, happy at being with him. Happy to be his females, perhaps. “Yaniri, yaniri,” I shouted. “Help me! Weren’t you a seripigari once? Come down and cure this foot of mine; I want to continue my journey.” But the talking monkey paid no attention to me. Can it be true that it was once, before, a seripigari who walked? That’s why it must not be hunted or eaten, perhaps. When you cook a talking monkey, the air is filled with the smell of tobacco, they say. The tobacco that the seripigari he once was used to inhale and drink in his trances.

The yaniri and his band of females had barely disappeared when the parrots came back. In even greater numbers. I began observing them. They were of every sort. Large, small, tiny; with long curved beaks or stubby ones; there were parakeets and toucans and macaws, but mostly cockatoos. All chattering loudly at the same time, without a letup, a thundering of parrots in my ears. I felt uneasy, looking at them. Slowly I looked at each and every one of them. What were they doing there? Something was going to happen, that was certain, in spite of my herbs against strange things. “What do you want, what are you saying?” I started screaming at them. “What are you talking about, what are you laughing at?” I was frightened, but also curious. I’d never seen so many all together. It couldn’t be by chance. It couldn’t be for no reason at all. So what was the explanation? Who had sent them to me?

Remembering Tasurinchi, the friend of fireflies, I tried to understand their chattering. Since they were all around me, talking so insistently, could they have come on my account? Were they trying, perhaps, to tell me something? I shut my eyes, listening closely, concentrating on their chatter. Trying to feel that I was a parrot. It wasn’t easy. But the effort made me forget the pain in my foot. I imitated their cries, their gurgles; I imitated their cooing. All the sounds they made. Then, between one pause and another, little by little, I began to hear single words, little lights in the darkness. “Calm down, Tasurinchi.” “Don’t be scared, storyteller.” “Nobody’s going to hurt you.” Understanding what they were saying, perhaps. Don’t laugh; I wasn’t dreaming. I could understand what they were saying more and more clearly. I felt at peace. My body stopped trembling. The cold went away. So they hadn’t been sent here by Kientibakori. Or by a machikanari’s spell. Could they have come out of curiosity, rather? To keep me company?

“That’s exactly the reason, Tasurinchi,” a voice murmured, standing out clearly from the others. Now there was no doubt. It spoke and I understood it. “We’re here to keep you company and keep your spirits up while you get well. We’ll stay here till you can walk again. Why were you frightened of us? Your teeth were chattering, storyteller. Have you ever seen a parrot eat a Machiguenga? We, on the other hand, have seen lots of Machiguengas eat parrots. Go ahead and laugh, Tasurinchi: it’s better that way. We’ve been following you for a long time. Wherever you go, we’re there. Haven’t you ever noticed before?”

I never had. In a trembling voice I asked: “Are you making fun of me?” “I’m telling the truth,” the parrot insisted, beating the leaves with its wings. “You’ve had to get a thorn stuck in you to discover your companions, storyteller.”

We had a long conversation, it seems. We talked together all the time I was there waiting for the pain to go away. While I held my foot to the fire to make it sweat, we talked. With that parrot; with others, too. They kept interrupting each other as we chatted. At times I couldn’t understand what they said. “Be quiet, be quiet. Speak a little more slowly, and one at a time.” They didn’t obey me. They were like all of you. Exactly like you. Why are you laughing so hard? You sound like parrots, you know. They never waited for one to finish speaking before they all started talking at once. They were pleased that we were able to understand each other at last. They nudged each other, flapping their wings. I felt relieved. Content. What’s happening is very strange, I thought.

“Luckily, you’ve realized we’re talkers,” one of them suddenly said. All the others were silent. There was a great stillness in the forest. “Now you doubtless understand why we’re here, accompanying you. Now you realize why we’ve been following you ever since you were born again and started walking and talking. Day and night; through forests, across rivers. You’re a talker too, aren’t you, Tasurinchi? We’re alike, don’t you think?”

Then I remembered. Each man who walks has his animal which follows him. Isn’t that so? Even if he doesn’t see it and never guesses which animal it is. According to what he is, according to what he does, the mother of the animal chooses him and says to her little one: “This man is for you, look after him.” The animal becomes his shadow, it seems. Was mine a parrot? Yes, it was. Isn’t it a talking animal? I knew it and felt that I’d known it from before. If not, why was it that I had always been particularly fond of parrots? Many times in my travels I’ve stopped to listen to their chattering and laughed at the uproar and all the flapping of wings. We were kinfolk, perhaps.

It’s been a good thing knowing that my animal is the parrot. I’m more confident now when I’m traveling. I’ll never feel alone again, perhaps. If I’m tired or frightened, if I feel angry about something, I know what to do now. Look up at the trees and wait. I don’t think I’ll be disappointed. Like gentle rain after heat, the chattering will come. The parrots will be there. Saying: “Yes, here we are, we haven’t abandoned you.” That’s doubtless why I’ve been able to journey alone for such a long time. Because I wasn’t journeying alone, you see.

When I first started wearing a cushma and painting myself with huito and annatto, breathing in tobacco through my nose and walking, many people thought it strange that I should travel alone. “It’s foolhardy,” they warned me. “Don’t you know the forest is full of horrible demons and obscene devils breathed out by Kientibakori? What will you do if they come out to meet you? Travel the way the Machiguengas do, with a youngster and at least one woman. They’ll carry the animals you kill and remove those that fall into your traps. You won’t become unclean from touching the dead bodies of the animals you’ve killed. And what’s more, you’ll have someone to talk to. Several people together are better able to deal with any kamagarinis that might appear. Who’s ever seen a Machiguenga entirely on his own in the forest!” I paid no attention, for in my wanderings I’d never felt lonely. There, among the branches, hidden in the leaves of the trees, looking at me with their green eyes, my companions were following me, most likely. I felt they were there, even if I didn’t know it, perhaps.

But that’s not the reason why I have this little parrot. Because that’s a different story. Now that he’s asleep, I can tell it to you. If I suddenly stop and start talking nonsense, don’t think I’ve gone out of my head. It will just mean that the little parrot has woken up. It’s a story he doesn’t like to hear, one which must hurt him as much as that nettle hurt me.

That was after.

I was headed toward the Cashiriari to visit Tasurinchi and I’d caught a cashew bird in a trap. I cooked it and started eating it, when suddenly I heard a lot of chattering just above my head. There was a nest in the branches, half hidden by a large spiderweb. This little parrot had just hatched. It hadn’t yet opened its eyes and was still covered with white mucus, like all chicks when they break out of the shell. I was watching, not moving, keeping very quiet, so as not to upset the mother parrot, so as not to make her angry by coming too near her newborn chick. But she was paying no attention to me. She was examining it closely, gravely. She seemed displeased. And suddenly she started pecking at it. Yes, pecking at it with her curved beak. Was she trying to remove the white mucus? No. She was trying to kill it. Was she hungry? I grabbed her by the wings, keeping her from pecking me, and took her out of the nest. And to calm her I gave her some leftovers of the cashew bird. She ate with gusto; chattering and flapping her wings, she ate and ate. But her big eyes were still furious. Once she’d finished her meal, she flew back to the nest. I went to look and she was pecking at the chick again. You haven’t woken up, my little parrot? Don’t, then; let me finish your story first. Why did she want to kill her chick? It wasn’t out of hunger. I caught the mother parrot by the wings and flung her as high in the air as I could. After flapping around a bit, she came back. Facing up to me, furious, pecking and squawking, she came back. She was determined to kill the chick, it seems.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Storyteller»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Storyteller» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Storyteller» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.