What did he talk about? It was impossible to remember. What a hodgepodge! A bit of everything, anything that came into his head. What he’d done the day before, and the four worlds of the Machiguenga cosmos; his travels, magic herbs, people he’d known; the gods, the little gods, and fabulous creatures of the tribe’s pantheon. Animals he’d seen and celestial geography, a maze of rivers with names nobody could possibly remember. Edwin Schneil had had to concentrate to follow the torrent of words that leapt from a cassava crop to the armies of demons of Kientibakori, the spirit of evil, and from there to births, marriages, and deaths in different families or the iniquities of the time of the tree-bleeding, as they called the rubber boom. Very soon Edwin Schneil found himself less interested in the storyteller than in the fascinated, rapt attention with which the Machiguengas listened to him, greeting his jokes with great roars of laughter or sharing his sadness. Their eyes avid, their mouths agape, not one pause, not a single inflection of what the man said was lost on them.

I listened to the linguist the way the Machiguengas had listened to the storyteller. Yes, they did exist, and were like the ones in my dreams.

“To tell the truth, I remember very little of what he said,” Edwin Schneil added. “I’m just giving you a few examples. What a mishmash! I can remember his telling about the initiation ceremony of a young shaman, with ayahuasca, under the guidance of a seripigari. He recounted the visions he’d had. Strange, incoherent ones, like certain modern poems. He also spoke of the properties of a little bird, the chobíburiti; if you crush the small bones of its wing and bury them in the floor of the hut, that assures peace in the family.”

“We tried his formula and it really didn’t work all that well,” Mrs. Schneil joked. “Would you say it did, Edwin?”

He laughed.

“The storytellers are their entertainment. They’re their films and their television,” he added after a pause, serious once more. “Their books, their circuses, all the diversions we civilized people have. They have only one diversion in the world. The storytellers are nothing more than that.”

“Nothing less than that,” I corrected him gently.

“What’s that you say?” he put in, disconcerted. “Well, yes. But forgive me for pressing one point. I don’t think there’s anything religious behind it. That’s why all this mystery, the secrecy they surround them with, is so odd.”

“If something matters greatly to you, you surround it with mystery,” it occurred to me to say.

“There’s no doubt about that,” Mrs. Schneil agreed. “The habladores matter a great deal to them. But we haven’t discovered why.”

Another silent shadow passed by and crackled, and the Schneils crackled back. I asked Edwin whether he’d talked with the old storyteller that time.

“I had practically no time to. I was exhausted when he’d finished talking. All my bones ached, and I fell asleep immediately. I’d sat for four or five hours, remember, without changing position, after having paddled against the current nearly all day. And listened to that chittering of anecdotes. I was all tuckered out. I fell asleep, and when I woke up, the storyteller had gone. And since the Machiguengas don’t like to talk about them, I never heard anything more about him.”

There he was. In the murmurous darkness of New Light all around me I could see him: skin somewhere between copper and greenish, gathered by the years into innumerable folds; cheekbones, nose, and forehead decorated with lines and circles meant to protect him from the claws and fangs of wild beasts, the harshness of the elements, the enemy’s magic and his darts; squat of build, with short muscular legs and a small loincloth around his waist; and no doubt carrying a bow and a quiver of arrows. There he was, walking amid the bushes and the tree trunks, barely visible in the dense undergrowth, walking, walking, after speaking for ten hours, toward his next audience, to go on with his storytelling. How had he begun? Was it a hereditary occupation? Was he specially chosen? Was it something forced upon him by others?

Mrs. Schneil’s voice erased the image. “Tell him about the other storyteller,” she said. “The one who was so aggressive. The albino. I’m sure that will interest him.”

“Well, I don’t know whether he was really an albino.” Edwin Schneil laughed in the darkness. “Among ourselves, we also called him the gringo.”

This time it hadn’t been by chance. Edwin Schneil was staying in a settlement by the Timpía with a family of old acquaintances, when other families from around about began arriving unexpectedly, in a state of great excitement. Edwin became aware of great palavers going on; they pointed at him, then went off to argue. He guessed the reason for their alarm and told them not to worry; he would leave at once. But when the family he was staying with insisted, the others all agreed that he could stay. However, when the person they were waiting for appeared, another long and violent argument ensued, because the storyteller, gesticulating wildly, rudely insisted that the stranger leave, while his hosts were determined that he should stay. Edwin Schneil decided to take his leave of them, telling them he didn’t want to be the cause of dissension. He bundled up his things and left. He was on his way down the path toward another settlement when the Machiguengas he’d been staying with caught up with him. He could come back, he could stay. They’d persuaded the storyteller.

“In fact, nobody was really convinced that I should stay, least of all the storyteller,” he added. “He wasn’t at all pleased at my being there. He made his feeling of hostility clear to me by not looking at me even once. That’s the Machiguenga way: using your hatred to make someone invisible. But we and that family on theTimpía had a very close relationship, a spiritual kinship. We called each other ‘father’ and ‘son’…”

“Is the law of hospitality a very powerful one among the Machiguengas?”

“The law of kinship, rather,” Mrs. Schneil answered. “If ‘relatives’ go to stay with their kin, they’re treated like princes. It doesn’t happen often, because of the great distances that separate them. That’s why they called Edwin back and resigned themselves to his hearing the storyteller. They didn’t want to offend a ‘kinsman.’ ”

“They’d have done better to be less hospitable and let me leave.” Edwin Schneil sighed. “My bones still ache and my mouth even more, I’ve yawned so much remembering that night.”

It was twilight and the sun had not yet set when the storyteller began talking, and he went on with his stories all night long, without once stopping. When at last he fell silent, the light was gilding the tops of the trees and it was nearly mid-morning. Edwin Schneil’s legs were so cramped, his body so full of aches and pains, that they had to help him stand up, take a few steps, learn to walk again.

“I’ve never felt so awful in my life,” he muttered. “I was half dead from fatigue and physical discomfort. An entire night fighting off sleep and muscle cramp. If I’d gotten up, they would have been very offended. I only followed his tales for the first hour, or perhaps two. After that, all I could do was to keep trying not to fall asleep. And hard as I tried, I couldn’t keep my head from nodding from one side to the other like the clapper of a bell.”

He laughed softly, lost in his memories.

“Edwin still has nightmares remembering that night’s vigil, swallowing his yawns and massaging his legs.” Mrs. Schneil laughed.

“And the storyteller?” I asked.

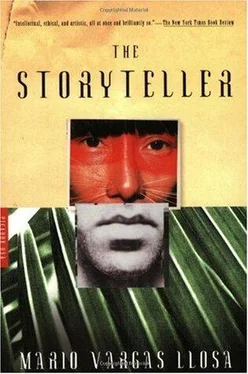

“He had a huge birthmark,” Edwin Schneil said. He paused, searching his memories or looking for words to describe them. “And hair redder than mine. A strange person. What the Machiguengas call a serigórompi. Meaning an eccentric; someone different from the rest. Because of that carrot-colored hair of his, we called him the albino or the gringo among ourselves.”

Читать дальше