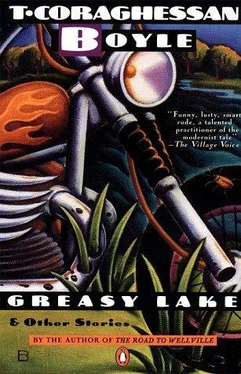

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Coburn did the best he could, but the following November, Colin, Carter, and Rutherford jumped parties and began a push to re-elect the man I’d defeated in ’84 on the New Moon ticket. He was old — antediluvian, in fact — but not appreciably changed in either appearance or outlook, and he was swept into office in a landslide. The New Moon, which had been blamed for everything from causing rain in the Atacama to fomenting a new baby boom, corrupting morals, bestializing mankind, and making the crops grow upside down in the Far East, was obliterated by a nuclear thunderbolt a month after he took office.

On reflection, I can see that I was wrong — I admit it. I was an optimist, I was aggressive, I believed in man and in science, I challenged the heavens and dared to tamper with the face of the universe and its inscrutable design — and I paid for it as swiftly and surely as anybody in all the tragedies of Shakespeare, Sophocles, and Dashiell Hammett. Gina dropped me like a plate of hot lasagna and went back to her restaurant, Colin stabbed me in the back, and Coburn, once he’d taken over, refused to refer to me by name — I was known only as his “predecessor.” I even lost Lorna. She left me after the debacle of the unveiling and the impeachment that followed precipitately on its heels, left me to “explore new feelings,” as she put it. “I’ve got to get it out of my system,” she told me, a strange glow in her eyes. “I’m sorry, George.”

Hell yes, I was wrong. But just the other night I was out on the lake with one of the Secret Service men — Greg, I think it was — fishing for yellow perch, when the moon — the age-old, scar-faced, native moon — rose up out of the trees like an apparition. It was yellow as the underbelly of the fish on the stringer, huge with atmospheric distortion. I whistled. “Will you look at that moon,” I said.

Greg just stared at me, noncommittal.

“That’s really something, huh?” I said.

No response.

He was smart, this character — he wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot pole. I was just talking to hear myself anyway. Actually, I was thinking the damn thing did look pretty cheesy, thinking maybe where I’d gone wrong was in coming up with a new moon instead of just maybe bulldozing the old one or something. I began to picture it: lie low for a couple years, then come back with a new ticket— Clean Up the Albedo, A New Face for an Old Friend, Save the Moon!

But then there was a tug on the line, and I forgot all about it.

Not a Leg to Stand On

Calvin Tompkins is just lifting the soda bottle to his lips when the German-made car brakes in front of the house and the woman with the mean little eyes and the big backside climbs out in a huff. “Where’d you get that?” she demands, shoving through the hinge-sprung gate on feet so small it’s astonishing they can support her. The old man doesn’t know what to say. He can tell you the dimensions of the biggest hotdog ever made or Herbert Hoover’s hat size, but sometimes, with the rush of things, it’s all he can do to hold up his end of a conversation. Now he finds himself entirely at a loss as the big woman sways up the rotted steps to the rot-gutted porch and snatches the bottle out of his hand.

“Patio soda!” The way she says it is an indictment, her voice pinched almost to a squeal and the tiny feet stamping in outrage. “I am the only one that sells it for ten miles around here, and I want to know where you got it. Well?”

Frail as an old rooster, Calvin just gapes up at her.

She stands there a moment, her lips working in rage, the big shoulders, bosom, and belly poised over the old man in the wheelchair like an avalanche waiting to happen, then flings the bottle down in disgust. “ Mein Gott, you people!” she says, and suddenly her eyes are wet.

It is then that Ormand, shadowed by Lee Junior, throws back the screen door with a crash and lurches out onto the porch. He’s got a black bottle of German beer in his hand and he’s unsteady on his feet. “What the hell’s goin’ on here?” he bellows, momentarily losing his footing in the heap of rags, cans, and bottles drifted up against the doorframe like detritus. Never graceful, he catches himself against the near post and sets the whole porch trembling, then takes a savage swipe at a yellow K-Mart oilcan and sends it rocketing out over the railing and up against the fender of the rusted, bumper-blasted Mustang that’s been sitting alongside the house as long as the old man can remember.

“You know what is going on,” the woman says, holding her ground. “You know,” she repeats, her accent thickening with her anger, “because you are a thief!”

Ormand is big, unshaven, dirty. At twenty-two, he already has a beer gut. “Hell I am,” he says, slurring his words, and the old man realizes he’s been helping himself to the pain pills again. Behind Ormand, Lee Junior bristles. He too, Calvin now sees, is clutching a black bottle.

“Thief!” the woman shouts, and then she begins to cry, her face splotched with red, the big bosom heaving. Watching her, the old man feels a spasm of alarm: why, she’s nothing but a young girl. Thirty years old, if that. For a keen, sharp instant her grief cuts at him like a saw, but then he finds himself wondering how she got so fat. Was it all that blood sausage and beer she sells? All that potato salad?

Now Lee Junior steps forward. “You got no right to come around here and call us names, lady — this is private property.” He is standing two feet from her and he is shouting. “Why don’t you get your fat ass out of here before you get hurt, huh?”

“Yeah,” Ormand spits, backing him up. “You can’t come around here harassing this old man — he’s a veteran, for Christ’s sake. You keep it up and I’m going to have to call the police on you.”

In that instant, the woman comes back to life. The lines of her face bunch in hatred, the lips draw back from her teeth, and suddenly she’s screaming. “You call the police on me!? Don’t make me laugh.” Across the street a door slams. People are beginning to gather in their yards and driveways, straining to see what the commotion is about. “Pigs! Filth!” the woman shrieks, her little feet dancing in anger, and then she jerks back her head and spits down the front of Lee Junior’s shirt.

The rest is confusion. There’s a struggle, a stew of bodies, the sound of a blow. Lee Junior gives the woman a shove, somebody slams into Calvin’s wheelchair, Ormand’s voice cracks an octave, and the woman cries out in German; the next minute Calvin finds himself sprawled on the rough planks, gasping like a carp out of water, and the woman is sitting on her backside in the dirt at the foot of the stairs.

No one helps Calvin up. His arm hurts where he threw it out to break his fall, and his hip feels twisted or something. He lies very still. Below him, in the dirt, the woman just sits there mewling like a baby, her big lumpy yellow thighs exposed, her socks gray with dust, the little doll’s shoes worn through the soles and scuffed like the seats on the Number 56 bus.

“Get the hell out of here!” Lee Junior roars, shaking his fist. “You… you fat-assed”—here he pauses for the hatred to rise up in him, his face coiled round the words—“Nazi bitch!” And then, addressing himself to Mrs. Tuxton’s astonished face across the street, and to Norm Cramer, the gink in the Dodgers cap, and all the rest of them, he shouts: “And what are you lookin’ at, all of you? Hugh?”

Nobody says a word.

Two days later Calvin is sitting out on the porch with a brand-new white plaster cast on his right forearm, watching the sparrows in the big bearded palm across the way and rehearsing numbers by way of mental exercise—5,280 feet in a mile, eight dry quarts in a peck — when Ormand comes up round the side of the house with a satchel of tools in his hand. “Hey, Calvin, what’s doin’?” he says, clapping a big moist hand on the old man’s shoulder. “Feel like takin’ a ride?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.