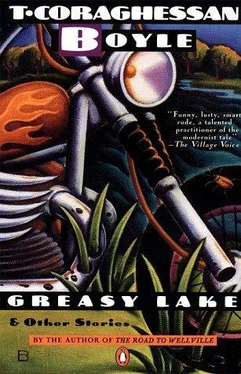

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The gypsies, Trekkies, diviners, haruspexes, and the like were apparently pursuing a collective cosmic experience, something that would ignite the heavens; the execs — from U.S. Steel to IBM to Boeing to American Can — wanted contracts. After all, the old moon was some 2,160 miles in diameter and eighty-one quintillion tons of dead weight, and they figured whatever we were going to do would take one hell of a lot of construction. Kaiser proposed an aluminum-alloy shell filled with Styrofoam, to be shuttled piecemeal into space and constructed by robots on location. The Japanese wanted to mold it out of plastic, while Firestone saw a big synthetic golf-ball sort of thing and Con Ed pushed for a hollow cement globe that could be used as a repository for nuclear waste. And it wasn’t just the big corporations, either — it seemed every crank in the country was suddenly a technological wizard. A retired gym teacher from Sacramento suggested an inflatable ball made of simulated pigskin, and a pizza magnate from Brooklyn actually proposed a chicken-wire sphere coated with raw dough. Bake it with lasers or something, he wrote, it’ll harden like rock. Believe me. During those first few heady months in office the proposals must have come in at the rate of ten thousand a day.

If I wasn’t equipped to deal with them (I’ve always been an idea man myself), Gina was. She conferred before breakfast, lunched three or four times a day, dined and brunched, and kept a telephone glued to her head as if it were a natural excrescence. “No problem,” she told me. “I’ll have a proposal for you by June.”

She was true to her word.

I remember the meeting at which she presented her findings as keenly as I remember my mother’s funeral or the day I had my gall bladder removed. We were sitting around the big mahogany table in the conference room, sipping coffee. Gina flowed through the door in a white caftan, her arms laden with clipboards and blueprints, looking pleased with herself. She took a seat beside Lorna, exchanged a bit of gossip with her in a husky whisper, then leaned across the table and cleared her throat. “Glitter,” she said, “that’s what we want, Georgie. Something bright, something to fill up the sky and screw over the astrological charts forever.” Lorna, who’d spent the afternoon redesigning the uniforms of the Scouts of America (they were known as Space Cadets now, and the new unisex uniforms were to feature the spherical New Moon patch over the heart), sat nodding at her side. They were grinning conspiratorially, like a pair of matrons outfitting a parlor.

“Glitter?” I echoed, smiling into the face of their enthusiasm. “What did you have in mind?”

The Madame closed her heavy-lidded gypsy eyes for a moment, then flashed them at me like a pair of blazing guns. “The Bonaventure Hotel, Georgie — in L.A.? You know it?”

I shook my head slowly, wondering what she was getting at.

“Mirrors,” she said.

I just looked at her.

“Fields of them, Georgie, acres upon acres. Just think of the reflective power! Our moon, your moon — it’ll outshine that old heap of rock and dust ten times over.”

Mirrors. The simplicity of it, the beauty. I felt the thrill of her inspiration, pictured the glittering triumphant moon hanging there like a jewel in the sky, bright as a supernova, bright as the star of Bethlehem. No, brighter, brighter by far. The flash of it would illuminate the darkest corners, the foulest alleys, drive back the creatures of darkness and cut the crime rate exponentially. George L. Thorkelsson, I thought, light giver. “Yes,” I said, my voice husky with emotion, “yes.”

But Filencio Salmon, author of The Ravishers of Pentagord and my chief speech writer, rose to object. “Wees all due respet, Meeser Presiden, these glass globe goin’ to chatter like a gumball machine the firs’ time a meteor or anytin’ like that run into it. What you wan eeze sometin’ strong, Teflon maybe.”

“Not shiny enough,”Gina countered, exchanging a hurt look with Lorna. Obviously she hadn’t thought very deeply about the thing if she hadn’t even taken meteors into account. Christ, she was secretary for Lunar Affairs, with two hundred JPL eggheads, selenologists, and former astronauts on her staff, and that was the best she could come up with?

I leaned back in my chair and looked over the crestfallen faces gathered round the table — Gina, Lorna, Salmon, my national security adviser, the old boy in the Philip Morris outfit we sent out for sandwiches. “Listen,” I said, feeling wise as Solomon, “the concept is there — we’ll work out a compromise solution.”

No one said a word.

“We’ve got to. The world’s depending on us.”

We settled finally on stainless steel. Well buffed, and with nothing out there to corrode it, it would have nearly the same reflective coefficient as glass, and it was one hell of a lot more resistant. More expensive too, but when you’ve got a project like this, what’s a hundred billion more or less? Anyway, we farmed out the contracts and went into production almost immediately. We had decided, after the usual breast-beating, shouting matches, resignations, and reinstatements, on a shell of jet-age plastic strengthened by steel girders, and a facade — one side only — of stainless-steel plates the size of Biloxi, Mississippi. Since we were only going up about eighty thousand miles, we figured we could get away with a sphere about one-third the size of the old moon: its proximity to earth would make it appear so much larger.

I don’t mean to minimize the difficulty of all this. There were obstacles both surmountable and insurmountable, technologies to be invented, resources to be tapped, a great wealthy nation to be galvanized into action. My critics — and they were no small minority, even in those first few euphoric years — insisted that the whole thing was impossible, a pipe dream at best. They were defeatists, of course, like Colin (for whom, by the way, I found a nice little niche in El Salvador as assistant to the ambassador’s body-count man), and they didn’t faze me in the least. No, I figured that if in the space of the six years of World War II man could go from biplanes and TNT to jets and nuclear bombs, anything was possible if the will was there. And I was right. By the time my first term wound down we were three-quarters of the way home, the economy was booming, the unemployment rate approaching zero for the first time since the forties, and the Cold War defrosted. (The Russians had given over stockpiling missiles to work on their own satellite project. They were rumored to be constructing a new planet in Siberia, and our reconnaissance photos showed that they were indeed up to something big — something, in fact, that looked like a three-hundred-mile-long eggplant inscribed at intervals with the legend NOVAYA SMOLENSK.) Anyway, as most of the world knows, the Republicans didn’t even bother to field a candidate in ’88, and New Moon fever had the national temperature hovering up around the point of delirium.

Then, as they say, the shit hit the fan.

To have been torn to pieces like Orpheus or Mussolini, to have been stretched and broken on the rack or made to sing “Hello, Dolly” at the top of my lungs while strapped naked to a carny horse driven through the House of Representatives would have been pleasure compared to what I went through the night we unveiled the New Moon. What was to have been my crowning triumph — my moment of glory transcendent — became instead my most ignominious defeat. In an hour’s time I went from savior to fiend.

For seven years, along with the rest of the world, I’d held my breath. Through all that time, through all the blitz of TV and newspaper reports, the incessant interviews with project scientists and engineers, the straw polls, moon crazes, and marketing ploys, the New Moon had remained a mystery. People knew how big it was, they could plot its orbit and talk of its ascending and descending nodes and how many million tons of materials had gone into its construction — but they’d yet to see it. Oh, if you looked hard enough you could see that something was going on up there, but it was as shadowy and opaque as the blueprint of a dream. Even with a telescope — and believe me, many’s the night I spent at Palomar with a bunch of professional stargazers, or out on the White House lawn with the Questar QM 1 Lorna gave me for Christmas — you couldn’t make out much more than a dark circle punched out of the great starry firmament as if with a cookie cutter.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.