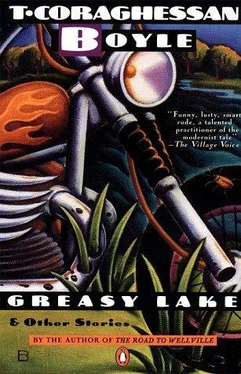

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Of course, we’d planned it that way. Right from the start we’d agreed that the best policy was to keep the world guessing — who wanted to see a piecemeal moon, after all, a moon that grew square by square in the night sky like some crazy checkerboard or something? This was no department store going up on West Twenty-third Street — this was something extraordinary, unique, this was the quintessence of man’s achievement on the planet, and it should be served up whole or not at all. It was Salmón, in a moment of inspiration, who came up with the idea of putting the reflecting plates on the far side, facing out on the deeps of the universe, and then swinging the whole business around by means of initial-thrust and retro-rockets for a triumphant — and politically opportune — unveiling. I applauded him. Why not? I thought. Why not milk this thing for everything it was worth?

The night of the unveiling was clear and moonless. Lorna sat beside me on the dais, regal and resplendent in a Halston moon-glow gown that cost more than the combined gross product of any six towns along the Iowa-Minnesota border. Gina was there too, of course, looking as if she’d just won a fettuccine cook-off in Naples, and the audience of celebrities, foreign ambassadors, and politicos gathered on the south lawn numbered in the thousands. Outside the gates, in darkness, three-quarters of a million citizens milled about with spherical white-moon candles, which were to be lit at the moment the command was given to swing the New Orb into view. Up and down the Eastern Seaboard, in Quebec and Ontario, along the ridge of the Smokies, and out to the verge of the Mississippi, a hush fell over the land as municipalities big and small cut their lights.

Ferenc Syzgies, the project’s chief engineer, delivered an interminable speech peppered with terms like “photometric function” and “fractional pore space,” Anita Bryant sang a couple of spirituals, and finally Luciano Pavarotti rose to do a medley of “Moon River,” “Blue Moon,” and “That’s Amore.” Lorna leaned over and took my hand as the horns stepped in on the last number. “Nervous?” she whispered.

“No,” I murmured, but my throat had thickened till I felt I was going to choke. They’d assured me there would be no foul-ups — but nothing like this had ever been attempted before, and who could say for sure?

“When-a the moon-a hits your eye like a big pizza pie,” sang Pavarotti, “that’s amore.” The dignitaries shifted in their seats, Lorna was whispering something I couldn’t hear, and then Coburn, the VP, was introducing me.

I stood and stepped to the podium to spontaneous, thrilling and sustained applause, Salmón’s speech clutched in my hand, the shirt collar chafing at my neck like a garrote. Flashbulbs popped, the TV cameras seized on me like the hungry eyes of great mechanical insects, faces leaped out of the crowd: here a senator I loathed sitting cheek by jowl with a lobbyist from the Sierra Club, there a sour-faced clergyman I’d prayed beside during a dreary rally seven years earlier. The glowing, corn-fed visage of Miss Iowa materialized just beneath the podium, and behind her sat Coretta King, Tip O’Neill, Barbra Streisand, Carl Sagan, and Mickey Mantle, all in a row. The applause went on for a full five minutes. And then suddenly the audience were on their feet and singing “God Bless America” as if their lives depended on it. When they were finished, I held up my hands for silence and began to read.

Salmon had outdone himself. The speech was measured, hysterical, opaque, and lucid. My voice rang triumphantly through the PA system, rising in eulogy, trembling with visionary fervor, dropping to an emotion-choked whisper as I found myself taking on everything from the birth of the universe to Conestoga wagons and pioneer initiative. I spoke of interstellar exploration, of the movie industry and Dixieland jazz, of the great selfless, uncontainable spirit of the American people, who, like latter-day Prometheuses, were giving over the sacred flame to the happy, happy generations to come. Or something like that. I was about halfway through when the New Orb began to appear in the sky over my shoulder.

The first thing I remember was the brightness of it. Initially there was just a sliver of light, but the sliver quickly grew to a crescent that lit the south lawn as if on a July morning. I kept reading. “The gift of light,” I intoned, but no one was listening. As the thing began to swing round to full, the glare of it became insupportable. I paused to gaze down at the faces before me: they were awestruck, panicky, disgusted, violent, enraptured. People had begun to shield their eyes now; some of the celebrities and musicians slipped on sunglasses. It was then that the dogs began to howl. Faintly at first, a primal yelp here or there, but within thirty seconds every damn hound, mongrel, and cur in the city of Washington was baying at the moon as if they hadn’t eaten in a week. It was unnerving, terrifying. People began to shout, and then to shove one another.

I didn’t know what to do. “Well, er,” I said, staring into the cameras and waving my arm with a theatrical flourish, “ladies and gentlemen, the New Moon!”

Something crazy was going on. The shoving had stopped as abruptly as it had begun, but now, suddenly and inexplicably, the audience started to undress. Right before me, on the platform, in the seats reserved for foreign diplomats, out over the seething lawn, they were kicking off shoes, hoisting shirt fronts and brassieres, dropping cummerbunds and Jockey shorts. And then, incredibly, horribly, they began to clutch at one another in passion, began to stroke, fondle, and lick, humping in the grass, plunging into the bushes, running around like nymphs and satyrs at some mad bacchanal. A senator I’d known for forty years went by me in a dead run, pursuing the naked wife of the Bolivian ambassador; Miss Iowa disappeared beneath the rhythmically heaving buttocks of the sour-faced clergyman; Lorna was down to a pair of six-hundred-dollar bikini briefs and I suddenly found to my horror that I’d begun to loosen my tie.

Madness, lunacy, mass hypnosis, call it what you will: it was a mess. Flocks of birds came shrieking out of the trees, cats appeared from nowhere to caterwaul along with the dogs, congress-men rolled about on the ground, grabbing for flesh and yipping like animals — and all this on national television! I felt lightheaded, as if I were about to pass out, but then I found I had an erection and there before me was this cream-colored thing in a pair of high-heeled boots and nothing else, Lorna had disappeared, it was bright as noon in Miami, dogs, cats, rats, and squirrels were howling like werewolves, and I found that somehow I’d stripped down to my boxer shorts. It was then that I lost consciousness. Mercifully.

These days, I am not quite so much in the public eye. In fact, I live in seclusion. On a lake somewhere in the Northwest, the Northeast, or the Deep South, my only company a small cadre of Secret Service men. They are laconic sorts, these Secret Service men, heavy of shoulder and head, and they live in trailers set up on a ridge behind the house. To a man, they are named Greg or Craig.

As those who read this will know, all our efforts to modify the New Moon (Coburn’s efforts, that is: I was in hiding) were doomed to failure. Syzgies’s replacement, Klaus Erkhardt the rocket expert, had proposed tarnishing the stainless-steel plates with payloads of acid, but the plan had proved unworkable, for obvious reasons. Meanwhile, a coalition of unlikely bedfellows — Syria, Israel, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Great Britain, Argentina, the Soviet Union, and China among them — had demanded the “immediate removal of this plague upon our heavens,” and in this country we came as close to revolution as we had since the 1770s.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.