For Milo,

who careened down the dunes and provided the electricity

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters; how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone is eating or opening a window

or just walking dully along.

— W. H. AUDEN, “MUSÉE DES BEAUX ARTS”

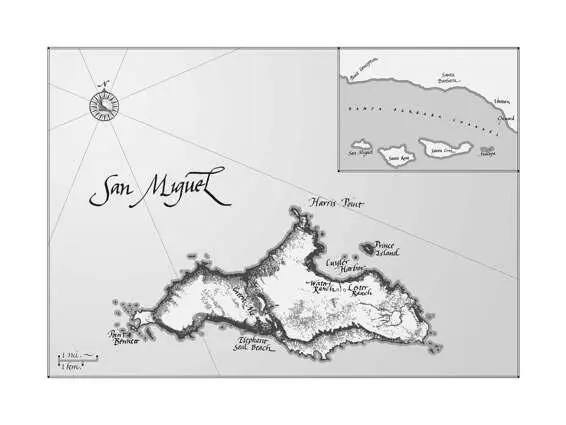

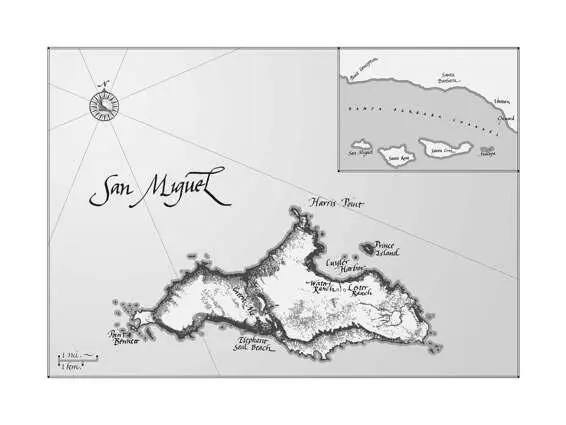

In retelling the story of the Waters and Lester families during their time on San Miguel Island, I have tried to represent the historical record as accurately as possible, and yet this is a work of fiction, not history, and dialogue, characters and incidents have necessarily been invented. I would like to acknowledge my debt to three texts in particular— The Legendary King of San Miguel, by Elizabeth Sherman Lester; San Miguel Island: My Childhood Memoir, 1930–1942 , by Betsy Lester Roberti; and Mrs. Waters’ Diary of Her Life on San Miguel Island, edited by Marla Daily — and to express my gratitude to both Marla Daily and Peggy Dahl for their kind assistance with the research for this book.

She was coughing, always coughing, and sometimes she coughed up blood. The blood came in a fine spray, plucked from the fibers of her lungs and pumped full of air as if it were perfume in an atomizer. Or it rose in her mouth like a hot metallic syrup, burning with the heat inside her till she spat it into the porcelain pot and saw the bright red clot of it there like something she’d given birth to, like afterbirth, but then what would she know about it since she’d never conceived, not with James, her first husband, and not with Will either. She was thirty-eight years old and she’d resigned herself to the fact that she would never bear a child, not in this lifetime. When she felt weak, when she hemorrhaged and the pain in her chest was like a medieval torture, like the peine forte et dure in which the torturer laid one stone atop the other till your ribs cracked and your heart stalled, she sometimes felt she wouldn’t even live to see the year out.

But that was gloomy thinking and she wasn’t going to have it, not today. Today she was hopeful. Today was New Year’s Day, the first day of her new life, and she was on an adventure, sailing in a schooner out of Santa Barbara with her second husband and her adopted daughter, Edith, and half the things she owned in this world, bound for San Miguel Island and the virginal air Will insisted would make her well again. And she believed him. She did. Believed everything he said, no matter the look on Carrie Abbott’s face when she first gave her the news. Marantha, no — you’re going where? Carrie had blurted out before she could think, setting down her teacup on the low mahogany table in her parlor overlooking San Francisco Bay and the white-capped waves that jumped and ran in parallel streaks across the entire breadth of the window. To an island? And where is it again? And then she’d paused, her eyes retreating. I hear the air is very good down there, she said, very salubrious, and the little coal fire she had going in the grate flared up again. And it’ll be warmer, certainly. Warmer than here, anyhow.

They’d been up before dawn, gathering their bags by lantern light on the porch of the rented house at Santa Barbara. If it had been warm the previous afternoon under a sun that shone sturdily out of a clear cerulean sky, it was raw and damp at that hour, the sky starless, the night draped like heavy cloth over the roof and the rail and the twin oleanders in the front yard. The calla lilies along the walk were dulled to invisibility. There wasn’t a sound to be heard anywhere. Edith said she could see her breath, it was so cold, and Marantha had held a hand before her own mouth, feeling girlish, and saw that it was true. But then Will had said something sharp to her — he was fretting over what they’d need and what they were sure to forget, working himself up — and the spell was broken. When the carriage came down the street from the livery, you could hear the footfalls of the horses three blocks away.

And now they were in a boat at sea, an astonishing transformation, as if they’d crept into someone else’s skin like the shape-shifters in the fairy stories she’d read aloud to Edith when she was little. A boat that pitched and rocked and shuddered down the length of it like a living thing. She was trying to hold herself very still, her eyes fixed straight ahead and her hands folded in her lap, thinking, of all things, about her stuffed chair in the front parlor of the apartment on Post Street they’d had to give up — picturing it as vividly as if she were sitting in it now. She could see the embroidery of the cushions and the lamp on the table, her cat curled asleep before the fire. Rain beyond the windows. Edith at the piano. The soft sheen of polished wood. That time seemed like years ago, though it had been what — a little over a month? The chair was in Santa Barbara now, the piano sold, the lamp in a crate — and the cat, Sampan, a Siamese she’d had since before they were married, given up for adoption because Will didn’t think it would travel. And he was right, of course. They could always get another cat. Cats were as plentiful as the grains of rice in the big brown sacks you saw in the window of the grocer’s in Chinatown.

She’d had a severe hemorrhage at the beginning of December, when they’d first come down to Santa Barbara, and she’d been too weak to do much of anything, but Will and Edith had set up the household for her, and that was a blessing. Except that now they were going to have to do it all over again, and in a place so remote and wild it might as well have been on the far side of the world. That was a worry. Of course it was. But it was an opportunity too — and she was going to seize it, no matter what Carrie Abbott might have thought, or anyone else either. She heard the thump of feet on the deck above. There was the sound of liquid — bilge, that was what they called it — sloshing beneath the floorboards. Everything stank of rot.

They’d been at sea four hours now and they had four more yet to go, and she knew that because Will had come down to inform her. “Bear up,” he’d told her, “we’re halfway there.” Easier said than done. The fact was that she felt sick in her stomach, though it was an explicable sickness, temporary only, and if she was ashamed of herself for vomiting in a tin pail and of the smell it made — curdled, rancid, an odor that hung round her like old wash — at least there would be an end to it. Will had admonished her and Edith not to put anything on their stomachs, but she’d been unable to sleep the night before and couldn’t help slipping into the kitchen in her nightgown when the whole house was asleep and feasting on the dainties left over from their abbreviated New Year’s Eve celebration — oyster soup, sliced ham, lady fingers — which would have gone to waste in any case. Now, as the boat rocked and the reek of the sea came to her in the cramped saloon, she regretted it all over again.

She was trying to focus on the far wall or hull or whatever they called it, sunk deep into the nest of herself, when Ida backed her way down the ladder from the deck above, grinning as if she’d just heard the best joke in the world. “Oh, it’s glorious out there, ma’am, blowing every which way.” The girl’s cheeks were flushed. Her hair had come loose under the bonnet, tangled black strands snaking out over the collar of her coat in a windblown snarl. “You should see it, you should.”

Читать дальше