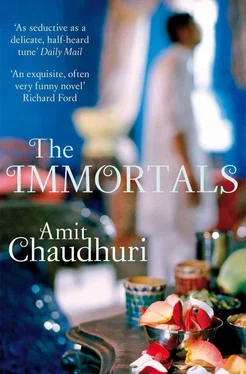

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘It’s a government hospital,’ said Mr Sengupta, as, without urgency, he buttoned a bush shirt with a floral print (the sort of fabric Nirmalya would never permit within inches of his skin) that his wife had bought him. (Her taste, even now, after her husband’s retirement, was unapologetically youthful.) ‘There’s no reason why you should have heard of it.’

A government hospital! Free care — but poor facilities. For Nirmalya, a government hospital was preceded by its reputation, by a premonition of its municipal, functional interior of transits and departures. Nirmalya wrinkled his nose, as if he could smell the phenyled corridors in the distance.

Once they had reached this awful but equably accommodating place — the government hospital was a handsome colonial building, and still had a residue of that air of stern justice that the Raj must have once appeared to have — they went to the first floor to the general ward. A large room on the left surprised them, with about ten beds, each quite near the other. Pyarelal — his bed wasn’t too far from the corridor — seemed to be taking a nap on this narrow, high, iron contraption; his eyes were shut. When the nurse told him he had visitors — ‘Dekho kaun aya’ — he opened them immediately. He’d been shaved in the morning; there was no shadow on the cheeks. They murmured their questions, Mallika Sengupta more probing and reproachful than the other two, as if the accident were somehow a result of a lapse in Pyarelal’s judgement, Nirmalya standing close to where the man’s legs were swathed in a green sheet, feeling that unexplainable child-like inner ease he experienced whenever he was close to him. Pyarelal answered in a sprightly way, admitting to his guilt with good humour; it was a bad fracture. Nirmalya kept glancing at the next bed, where a man, pretending to be deaf, was eating diligently from a metal tray carved into tinny crevasses that contained peas, subzi, roti, and daal that was drying into cold scabs at the edges. There was a smell of onions. To be so focussed on the hospital food, bent forward in that buttonless white shirt and loose pyjamas everybody here had to inhabit, seemed terribly lonely to Nirmalya, one man joined to the other by the camaraderie of exile; it was like having to deny, for that moment, what had nurtured and made you.

‘And food?’ asked Mrs Sengupta, frowning, challenging him.

Pyarelal smiled, the smile of a man who knew he was free. He gestured to a humble tiffin-carrier on the floor tucked next to his bed.

‘Food comes from home, didi,’ he said, deprecating but content.

A week later, Pyarelal was relocated in the tinctured safety of Dr Karkhanis’s nursing home, a cramped room with three beds that could be partitioned at will by frayed green curtains, a Voltas air conditioner shuddering in one wall, no windows anywhere so that visitors and convalescents were shielded from the contamination of daylight, connections behind the bedhead for monitors if they were needed, a little bedside table for a glass of water, Marie biscuits, and a banana: a chilly, nocturnal, crowded haven. The name of this orthopaedic surgeon sounded too perfectly apposite to Nirmalya not to be made up — ‘Karkhanis’ from ‘karkhana’ or ‘factory’: it was as if, improbably, the man and his very lineage specialised in spare parts for the body.

‘He’s fine,’ said the shambolic doctor when he had a moment to speak, with the succinctness of a harried but polite young man. ‘The wound is taking time to heal though. It’s a common problem with chronic smokers.’ And then, having imparted an implicit sense of understanding in the perspiring overcrowded corridor next to the lift, he, with a deft, not impolite, movement had shaken off the possibility of the next question, and was gone.

Nirmalya saw the bandaged leg later, as he stood next to the bed along with his mother and Tara, as she drew the screen to blot out the incumbent on a neighbouring chair, a man with well-combed hair with shirt buttons open up to just above the stomach, keeping vigil next to a puzzlingly well-looking woman.

‘Give them space,’ Pyarelal ordered Tara; she, suddenly yielding and obedient, stepped backward to make way for the visitors.

The lower leg beneath the pyjama was supported by a metal splint that had been screwed, it appeared to Nirmalya, on to the bone of the shin and ankle; an intimate streak of blood, like betel juice, had dribbled on to the dressing.

‘Well, you won’t be able to play the tabla with me next week,’ said Nirmalya, pressing his arm with the urgency of their early conversations, an urgency that returned in deceptive waves whenever they were together. Hidden in that clasp were all sorts of things; the first onrush of love, faded misunderstandings, mutual suspicion, and the memory of the transformation, the sense of possibility, that music brings. They’d once held that knowledge like a secret. ‘I was thinking of sitting for some practice. Maybe I can ask your son to play.’ Pyarelal’s son had learnt the tabla; it was going to be his profession too, the gharana deepening, continuing, then losing itself in the mundane.

Pyarelal at once looked apologetic, a bit confused — probably because he was no one’s guru. He’d taught people a few things, yes, but he had no official status. He’d taught Nirmalya many things, but Nirmalya’s guru was Shyamji; he didn’t dispute that. In private, he said to Tara: ‘Arrey, what did Shyam teach him? I taught him much more!’ And then the two of them, the small, darting man who could be full of pestilential fury, the large smouldering wife, became silent and heavy for a minute, probably for very different reasons.

* * *

LATER, AT THE close of the year, as the gentle month of December approached, bright and polished, the sweatiness of October gone, the sun descending marginally early on Marine Drive, Banwari, Shyamji’s younger brother, and Shyamji’s son Sanjay went about half-heartedly trying to set up the Gandharva Sammelan. They would soon be here from California, Zakir Hussain and Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi Shankar, the proscenium was being erected in the St Xavier’s quadrangle, you’d have to plan the evenings accordingly with the thin, bangled girls in their shawls and blue jeans. It was a matter of prestige, in the midst of all this, to try to keep the Gandharva Sammelan going. But the irony of having to place Shyamji’s portrait next to Ram Lal’s! For Sumati, that framed picture, taken in London, in Wembley, by a student, the face in it patient, not absolutely convinced by the moment, waiting for the click of the shutter — that picture, in these last months, had become for the newly lost and unmindful Sumati a mute companion.

Banwari, brushing his hair back, his absent gaze riveted to the mirror before he opened the door, and Sanjay, his head bowed, set out to scout for advertisements and donations; they went to the homes of former students, did their inaugural namaskars, descended upon drawing-room sofas, shook their heads and gazed heavenwards while accepting condolences. But most of the students didn’t want to sing. The sammelan, even with its crowded, inbred glamour, in which every singer was like a blessed and exceptional son or daughter in a single remarkable family, had lost its impetus. ‘Not this year,’ said Mallika Sengupta, while Mr Sengupta sat some distance away on the same sofa, not unsympathetic, in fact, perfectly democratic in his sympathies, understanding at once the dead man’s brother’s and son’s requirements as well as his wife’s reservations. The whole burden of opening the hardback songbook again — its spine had begun to break like an old, tattered hive — was too much for her. These bhajans hadn’t gone forever, no; Meera’s agonies over her phantom god, Tulsi chanting and chanting the name of Ram; she was confident they’d return to her. But she didn’t want to have anything to do with them just yet. ‘And, Banwariji,’ she added, glancing at her husband in a way that suggested he couldn’t speak for himself, ‘please don’t ask Sengupta saab for an advertisement. You know he’s not with the company any more.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.