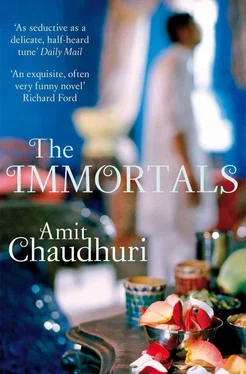

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The doorbell rang. The young servant opened the door, and a conversation of stops and starts, of monosyllables and broken sentences, could be heard taking place in an undertone; Mrs Sengupta, naturally curious, naturally suspicious, followed. ‘Achha?’ she could be heard exclaiming in disbelief; and then re-entered the sunlit perfection of the sitting room, as if she couldn’t keep the news from her son, displaying a mango in one hand, a faint stain like a shadow on one side of the skin. ‘This is from the tree in our compound,’ she said to Nirmalya, who was still immune to the taste of the fruit. ‘The watchman’ — the invisible interlocutor outside the door — ‘has given us a few’; more pleased than if it were a lottery draw.

‘He needn’t have died,’ said Nirmalya, shaking his head, chasing the thoughts that had been preoccupying him since she’d got up. ‘It was nothing but stupidity.’ He finished the tea. He saw Shyamji’s life, in the last few years, as a series of errors in judgement: choosing glamour over art, light music over classical, death over life. It wasn’t diabetes or even heart disease that had killed him; it wasn’t drink, or the hidden self-destructive impulse that finished other artists — Shyamji was a calm, reasonable man, who had no vices. It was wanting too much from life. ‘Why was he in such a hurry?’ he said irritably to Mrs Sengupta, as she stood there, solemnly listening, still delicately cupping the fruit. ‘Why couldn’t he wait?’

‘Didi, baba,’ said Pyarelal in an urgent, sheepish whisper, pretending to underplay the importance of his announcement, ‘my student Jayashree Nath — you’ve seen her, baba, in the Taj — will be dancing at the Little Theatre on the fifteenth. Please come. I want some samajhdaar, knowledgeable people in the audience. Baba is very samajhdaar — yes, absolutely!’

And so Nirmalya, who’d been conferred the status of ‘critic’ by Shyamji, and Mrs Sengupta, whose long, distracted line of music teachers since she moved to Bombay appeared to have abruptly and finally disbanded with Shyamji’s death — they, mother and son, in their old, persistent companionableness, were persuaded to set out that evening for the National Theatre of the Performing Arts, which hovered like a bleached fragment in their memory, because they used to see the white squat building across the waves every day from the balcony of Thacker Towers. An hour’s journey on the way, an hour in the Little Theatre, an hour returning; a quarter of the day, at the very least, spent on the cause of Jayashree Nath. But, getting ready, they were busy with anticipation; Mrs Sengupta, as ever, consuming the last twenty minutes applying the finishing touches to her face. It meant going to the other end of the city, where the land shrank into the sea: where Nirmalya had grown up, and dreamed, and looked out on the curving drive to school, and seldom been happy. Tara, Pyarelal’s wife, was waiting in the aisle of a hall in which people were still settling into seats; she said, ‘Aiye, didi, aao, baba, your gur’ — but she checked herself quickly before she said ‘guru’ — ‘your Pyarelalji was so excited that you’re coming.’ As Tara seated Nirmalya and Mrs Sengupta in the second row, she bent and, kohl-blackened eyes narrowing with her familiar teasing smile, said in Nirmalya’s ear: ‘See, your Pyarelalji’s new student Madhu is sitting next to you — woh jo film star.’ Once seated, Nirmalya glanced deftly to his right. He’d heard about Madhu; she’d acted in one film; it had been a great success. And she — a diminutive young woman, fair and light-eyed, pretty but not unusual, as ordinary as a college girl — was learning kathak dance from Pyarelal. Her chaperone, her mother, sat next to her — now, where had he read about her? It was a long time since he’d turned the pages of the magazines of film gossip his mother used to subscribe to when he was a child, skimming them objectively for a stray piece of titillating data. And now they took the stage, Pyarelal, stiff and small with reflected glory, then a wiry, bespectacled man who, aloof with what looked like a secret source of amusement, went and sat before the harmonium, and, anklets resonating, Jayashree Nath. Everyone clapped; Madhu joined her small, angelic hands to give them a warm ovation. Pyarelal, from behind the tablas, saw Nirmalya — the sort of glance of recognition, satisfaction, and subterfuge that’s exchanged between accomplices separated by crowds in busy places.

‘That’s Motilalji!’ whispered his mother.

She was looking straight at the wiry man, who’d begun to sing, straightaway climbing the high notes. Her teacher, who used to miss his lessons because he’d be fast asleep, lulled and sedated by drink in the mornings, who used to take some time during each lesson to both praise and insult her in his casual, perfunctory way: Sumati’s elder brother, Shyamji’s brother-in-law, who, late one morning, had taken the reticent ‘Shyam’ to her flat in Cumballa Hill with its long veranda of potted plants just because he wanted to show off — I have rich students like these. How embarrassed and compromised Shyamji, poor man, had been; and always uncomfortable, quick to move on to some other subject, on being reminded of that first visit.

‘So he’s singing again,’ she ruminated, not sure whether to feel surprised or intrigued.

Nirmalya listened carefully as he sang the thumri about Radha venturing towards the banks of the Jamuna; he’d heard Motilalji had once been a great singer, but, in the flat in Cumballa Hill, he’d been more interested in hide and seek, the ‘servants’ quarters’, and imaginary exigencies and companions. But, sober and recovered, this voice, whose actual timbre Nirmalya could hardly recall, lacked pliability and freshness, though he realised, once or twice with a thrill of recognition, that there were flashes of the old gift.

There were no microphones; the auditorium boasted special acoustics that were usually disappointing. And so, when Pyarelal spoke the bols of the tabla rapidly, or recited two lines from an Awadhi poem to his own grand tabla slapping, Nirmalya thought he’d have to strain to hear, but was surprised today that Pyarelal was clearly audible. The two items that followed the weaving of the thumri were staples of kathak dance, almost cliches; but novel and compelling to Nirmalya, who, silently watching the narratives dilate and ebb before him, still had a child’s innocence and enthusiasm about the world of Indian art: whatever was beautiful was incomparable, and endlessly more exciting than anything to be found in a European museum. It was the moment of Radha’s sringar: and as the wiry man sang, practised, unhesitating, noticeably without inspiration, Radha adorned herself before her tryst, consulting a mirror she held in her hand, examining herself from one angle, then another. The entire audience — kind-hearted Parsi ladies, buttoned-up marketing executives and their wives, men from advertisement agencies, fresh from composing copy, older couples from ‘cultured’ families, with the sheen of some rare substance about them, brazen regulars who’d strayed in for the air conditioning, all the usual migrants who made up an audience for a performance, preferring, for an hour, this interior to the shelter of home — everyone in the hall attended, for five minutes, to the beauty of Radha’s toilette, giving her the utter privacy to make herself up bit by bit.

Then, after satisfied applause, there was the episode of Draupadi’s rape — Yudhishthir’s last throw of the dice, accompanied by a dire, confirming thump on the tabla by Pyarelal; Shakuni’s bronchial laughter, his head thrown back; and then, for the millionth time since this story was born, Dushasana enlisted to strip Draupadi of the yard of cloth that covered her. And there was Krishna, beatific, almost smug, effortlessly extending the yard of cloth that the hapless Dushasana, puzzled, then vanquished, by the length of the sari, kept trying to pull off. And Nirmalya, lost in his seat in the spectacle, couldn’t help admiring the way Jayashree Nath, despite her unrelenting Hindi-film-style jerks of the head, became, disconcertingly, about a quarter of the cast of the Mahabharata. It was striking how what was really a magic trick, something worthy of a circus, had been transformed by Jayashree Nath and Pyarelal and Motilalji and kathak dance into an instance of the terrifying but undeniable dependence of human beings on divine intervention. Everyone was moved; it was as if, teetering on the brink of disaster, they’d glimpsed the smirking Krishna and fallen back into the safety of Bombay, the air-conditioned auditorium, the soft but resolute seats, and the knowledge that, outside, the cars were parked silently in rows by the Arabian Sea.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.