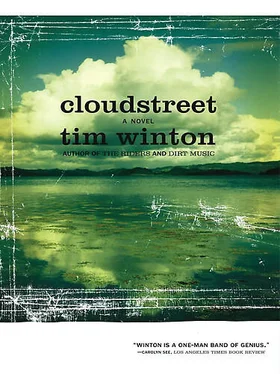

I’ve got a headache!

These days you are a headache. Put the kettle on.

Oriel Lamb tromped out the back to the privacy of the dunny and latched the door with great care. Whatever was going on with that husband of hers would need the kybosh put on, too. But today she wasn’t sure she was up to men.

Like a Light Shinin

Like a Light Shinin

The night before.

It’s dusk when Sam Pickles sees his tenant and neighbour come down from the back step into the yard. He’s been standing here a few minutes smoking and easing up. His clothes and his skin smell of metals and kerosene. These days after work his mouth tastes of copper. Out the back here by the splintery fence near the mulberry tree that towers on the Lamb side, it’s pleasant and cool and except for the muffled shouts of children in the house and the faraway carping of a dog, it’s quiet. Sam sees the other man stand still a moment with his hands in his pockets to look up at the pumpkin-coloured sky, then to spit and regard the ground at his feet with what looks like a great sobriety. He’s tall and thin; he’s beginning to stoop a little already, even though Sam guesses him to be about his own age. Maybe older, he thinks, maybe he’s forty — yes, come to think of it he’d be at least that. He looks like that cowboy cove, Randolph Scott. Since the night they arrived Sam has hardly spoken to his neighbours. They’re always working too damn hard to talk, and they’re not the sort of people to waste much time having fun.

Sam leans his elbows on the fence.

Gday, he calls.

Lester Lamb looks up from the ground, straight into the crown of the mulberry tree and then along the fence. His face changes when he recognizes who it is.

Oh. Gday there. Thought I was going daft. Sounded like you were in the tree.

Too tired to get up there.

Lester is coming down to stand beside him on the other side of the fence.

A man aches all over, Sam goes on.

Ah. Know how you feel.

Cepting I get all the ache down one side, you know, cause of this. He holds up his pruned hand. Lamb squints at it and murmurs a sympathetic sort of noise. See, Sam continues, I favour the other arm all the time. Makes it ache like buggery. Used to using both arms.

Lamb gives the stump a careful look.

They say you feel the pain, even when there’s nothing there. Told me that in the army.

Yeah. No lie. More an itch you get now and then, if you catch my drift, and a man goes to scratch it and there’s nothin to scratch. Sam sees his neighbour moving his mouth as if making up his mind whether or not to ask something, so he answers it anyway; a winch, says Sam. On a boat. Just bloody stupidity. And bad luck. You believe in luck, Mr Lamb?

Can’t say. Dunno. Didn’t used of. Anyway, call me Lest.

Orright, Lest. Call me Sam. Or landlord’ll do, if yer stuck for words.

They laugh and there’s a silence between them a while. So you do a lot of physical, then? Lester Lamb says, more confident now. Work, I mean.

Yeah. Well, not like before. This’s only from last summer. I’ve been on wharves and boats all me life. Funny, you know, I was a butcher’s apprentice four years and never even nicked meself. Now’m at the Mint. He laughs. Makin quids for everybody else.

Sam sees the look of respect come onto Lester’s face.

I’m a sort of utility man there, if you know what I mean. Lester clearly doesn’t and Sam feels chuffed. His neighbour seems to be reappraising him all of a sudden. You were in the army?

Last war, Lester says. I was a young bloke then.

Ah, I’ve got the asthma.

Right.

And the war wound.

Exactly.

You don’t believe in luck, you say.

Can’t say I’ve been persuaded by it.

Everythin’s easier to believe in when it comes a man’s way.

That’s true enough, I reckon, Lester says.

Sam pauses. He thinks about this. He feels like there’s gold in his veins but he’s not sure whether to tell.

I’m on a run, he says in the end.

How d’you mean?

Like I’m winnin. Luck. It’s like a light shinin on you. You can feel it.

Lester Lamb doesn’t look sceptical — not at all. He’s a farmboy, you can see it on him — honest as filth. The sun is gone and there’s only the faintest light in the sky, but Sam can still see the other man’s features. Cooking smells seep down to them, the sound of screaming kids, a passing train down the embankment.

I’ll show you, Sam says, with his heart fat in his neck. If you like.

Before dawn Rose heard the old man wheezing as he passed her door; she was suddenly awake. She lay still and listened. Her father’s boots on the stairs. Some whispering. She heard the front door sigh back on its hinges down there and she went to the window. Below, in the front yard, two silhouettes moved toward the Lambs’ truck, one short, the other tall. She knew who they were. Now they were pushing and shoving at the truck to get it rolling a little and it crept along flat old Cloud Street to the corner until it found the incline of Railway Parade and got up a good roll and was gone. Rose waited a few moments, heard the motor hawk into life and went back to bed. Whatever the old boy was up to was bound to be stupid, but she wouldn’t tell. Oh no. She’d been dead asleep the same as everyone else.

The smell of horses reminded Lester Lamb of a dozen things at once, almost all of them good. The worst thing he could associate horses with, apart from seeing rats eating up into their arses in Turkey, was having a stallion bite the back of his neck once when he was mending a fence. He turned on it and gave it a good whack between the eyes with the claw hammer and the damned thing fell on him and crushed the blasted fence for his trouble.

The track was quiet and dew-heavy in the early dawn, muffled in by the empty stands and sheds. Small lights showed in and around the stables. Horses neighed and spluttered. Timbers creaked from their weight. Men laughed quietly in little blear-eyed clumps and lit cigarettes. Sam Pickles led him down the soft dust of alleys between stables. Behind one shed a soldier and a woman were kissing. Lester saw a great swathe of flesh as the soldier slipped a hand up the woman’s leg. Sam whistled and the couple laughed, but Lester went prickly with embarrassment.

Sam stopped at a small tin hut and knocked. A little blue-chinned man opened up.

Gday, Sam. Pushin yer luck another furlong, eh?

Gis a coupla brownfellas, Macka, and somethin for the flask, orright?

Early start. Macka went in for a moment and came out with two big bottles of beer and a smaller bottle that could’ve been anything. Sam slipped him some money and they headed back down the alley. You could hear the gentle thrumming of hoofs on dirt. Out on the track a couple of trainers had horses just rolling along with a relaxed gait. Like men tuning cars, they had their heads cocked sideways or pressed into the great dark cowlings of flank, listening as they rode.

Never been here before, Lest?

No. Can’t say I have. The only time Lester had been at a racecourse before was back between the wars when there was a revival meeting out in the open one night. Families had driven and walked in from miles around to hear the gospel story and the man up front had shouted like an angel and glowed in the face as though he might go to flames any moment. They’d gone up the front, him and Oriel and the kids too, and the man had laid hands on them and Lester had felt the power. But that was a long time gone.

I’ve never really done any bettin before, neither.

Читать дальше

Like a Light Shinin

Like a Light Shinin