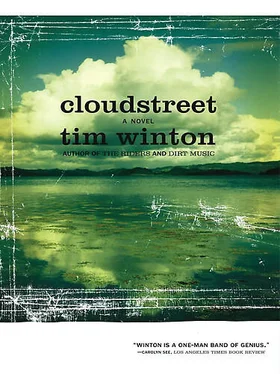

After the kids are asleep Dolly stands at the window with only her stockings on. There is no noise from next door, and the whole house is quiet. Sam lies on the bed, rolls a smoke, watching her. She looks out at the moon that rests on the fence.

We aren’t that old, she says.

Anyone with an arse like that isn’t real old. He licks the paper, tamps, then lights up.

Dolly rests an elbow on the sill. The grass is shin high out in their half of the yard. Bits of busted billycarts and boxes litter the place beneath the sagging clothesline.

I dunno what I’m doin, she says.

Do you ever?

She shrugs. Spose not. What about you?

He takes a drag. I’m a bloke. I work. I’m courtin the shifty shadow. That’s what I’m doin.

This is another life.

It’s the city. We own a house. We got tenants.

Do you remember Joel’s beach house?

Sorta question is that?

That was our life.

The late train rollicks up from Fremantle. It sends the long grass into rolling gasps and sighs on the embankment in the moonlight, and Dolly watches as Sam comes up behind her to fit snug against her rump. She feels the heat of his fag at her neck and his hand and his stump on the cold porcelain of her nipples, and the hot, glowing end of him getting up into her, making her twist and feint, grip the sill, see her nails bending in the wood. Dolly can smell the charge in him, it hisses against her stockings and bows her legs until it’s him that’s holding her upright, and so it goes, on and on, until out there in the moonlight she can see the river and the dunes and Joel’s shack, and the two of them on the beach rubbing the flesh of oysters into each other.

When Sam is asleep, Dolly gets up and pulls on a coat and creeps out of the house. The mob next door are long asleep. She goes down to the tracks and looks at them gleaming in the moony light; she can see her face in them, almost. She remembers riding out to the siding when she was a girl. She rode on the back of the saddle behind her father. Oh, she worshipped that man. He was strong and sunbrown and quiet. There was a way he had of laughing that made her feel like the world might stop right there and then, as if that laughter was enough for everyone and everything, and there was no point in anything else bothering to continue. She must have been six or so on that ride out to the siding where the great tin holding bins stood bending in the heat. The ground was blonde and rainstarved and after Dolly’s father had fixed up his business with the rail men he saw her standing by the buckled railway lines.

Those rails go all over the world. They go forever.

And she felt it was true. It was like they were electric with all knowledge, all places, all people.

Dolly squats by the cold rails here in the winter night.

She never did get to try those rails. She just got to be goodlooking and cheeky and by sixteen she found herself out on her back under the night sky with a long procession of big hatted men, one of whom, the youngest, the fairest of them, was sleeping up there in that saggy great house with his arms up behind his head, and his fingerless fist on her pillow. No, she never did find out about those rails. But nothing ever turns out like you expect. Like how your father ends up not being your father, and all.

Dogs get howling all down the way. Somewhere a bicycle bell rings. Somewhere else there’s a war on. Somewhere else people turn to shadows and powder in an instant and the streets turn to funnels and light the sky with their burning. Somewhere a war is over.

Bells

Bells

Rose woke up to the sound of bells. She opened her window and the world was mad with noise: church bells, tram bells, air raid sirens, train whistles, a rocket going up, klaxons and trumpets, dogs howling nutheaded at the sky. Cloud Street was filling and below, the shop was bursting with huggers and clappers who were opening bottles and crying out on the lawn where she could see them. The house shook and a thousand smells whirled through it with a bang of doors.

The war is over!

Ted came bursting in: The Japs! We creamed em!

It’s finished, listen to the wireless.

Rose rushed to the landing. Downstairs she saw that Mrs Lamb giving her mum a roast chook and a plate of fruit. The old man was breaking open a bottle of grog he’d got from who knows where. There were a couple of Yank sailors out in the hallway and that wet eyed Mr Lamb squeezing his accordion fit to wring blood from it.

She went down into it and couldn’t help but have a smile cracking her chops. She danced a barn dance with a Yank and got a smack across the bum passing the old man on the verandah.

Here, said Quick Lamb, holding out a jar of humbugs.

She went elbow deep for them.

Mum’ll kill us, he said.

Me! said the slow kid, the goodlooking one who was on the front step spinning a butter knife. The blade pointed at his chest. It’s meeee!

THAT’S it, Sam thinks; that’s bloody it. The streets are still full of revellers as he heads for the station with his pennies in his pocket. This is the break in the weather, Sam my man. Come in bloody Spinner.

His teeth ache. His hair buzzes at its roots with power.

Wherever it is, I’ll find it.

Whoever it is, I’ll find em.

And I won’t be back till I do.

Makin Millions

Makin Millions

A couple of days after VJ Day, when everyone was still crazy with peace fever, and the old man still hadn’t turned up and the old girl was getting vicious, Rose walked home from school with her booklumpy bag, wondering if he was gone for good and how she’d have to tough it out with the old girl. It was torture. Other kids swept past on junky grids, pulling wheelies and skids in the dirt, startling clumps of gossiping girls and sending small boys up trees in fright, but Rose walked straight and sensible as though nothing could touch her. Up ahead she saw the Lambs shagging along under the Geraldton wax that burst over the fences beside the station and hung full of bees and fragrance. Somewhere behind her, Ted was shouting at Chub not to be such a wanker and that he could flaminwell carry his own bag.

If the old man was gone another day, she reckoned, that Mrs Lamb’d be over with some advice quicksmart. She knew the fast, cheap, clean, sensible way of doing everything and she’d be dishing it out like the Salvos, and the old girl’d be pukin.

Rose stopped by the Geraldton wax. Geraldton. Already it seemed like something she’d dreamt up. She pulled a waxy blossom off its stem and took it with her.

Kids were milling round Cloudstreet buying penny-sticks, freckles, snakes and milkbottles in little white paper bags. Rose pushed through the congregation on the verandah, heaved open the big jarrah front door and went inside.

And there he was. Arms akimbo, like General Douglasflamin-MacArthur, the old man was sitting at the bottom of the stairs, polishing his stumpy knuckles and grinning fit to be in pictures.

You look like you lost a penny and found a quid, she said.

Sam held out his two-up pennies.

Where you been?

A bit of scientific work.

Oh, gawd. So what are you grinnin about, then?

I got ajob.

A job! How?

The shifty shadow, Rosie.

Читать дальше

Bells

Bells