The boy continues to talk as Mikal hears the noise of someone weeping in a nearby cage, the sound of someone praying, the barking of dogs. Though full of fatigue he focuses on everything in an effort to remain awake — fearful that he might talk in his sleep and reveal something. But the struggle to keep his eyes open is only intermittently successful. During sleep he sees someone rinsing a red garment in flowing water. Moving it around in the current. He approaches and sees that it is not a garment, but his blood, the liquid taken out of Mikal’s body as one article and entity, and being sluiced in the river, all his knowledge being extracted from it.

*

Three white men enter the interrogation booth — that smells of vomit — and begin to shout at him without the interpreter translating any of the words, just screaming into Mikal’s face for more than ten minutes. Then suddenly they stop and leave.

*

‘Did you get the women safely out of the mosque?’ Mikal hears himself asking David.

‘Tell me about Jeo.’

Mikal looks up from the table.

‘Jeo has told me everything about you two.’

‘You have Jeo?’

‘Stay in your chair.’

‘I want to see him.’

‘Impossible. Stay in the chair.’

‘Where is he?’

‘He has told us everything.’

‘There is nothing to tell. Where is Jeo? Is he all right?’

‘Tell us which escape routes the Arab fighters are using to get out of Afghanistan into Pakistan and Iran.’

‘I want to see Jeo.’

‘He says you took a bayt of loyalty to Osama bin Laden two years ago.’ He uses the Arabic word — bayt , a blood oath.

‘You are lying.’

‘Either I am or he is. I am telling you what he told me.’

‘I want to see him.’

‘So it’s a lie?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why would he lie to us?’

‘I don’t know.’ Suddenly a terrible possibility enters his head. ‘What did you do to him to make him confess to that?’

‘Stay in your chair,’ the Military Policeman says loudly from his corner. He stands up to his full height which is well over six feet, obscuring the poster behind him. Talking about the Moroccan and his bandaged head, Akbar said that a female interrogator had asked him how he’d felt when he heard about the attacks on the Twin Towers. The Moroccan said that he had been ecstatic, and when she told him that the first boy she had ever kissed had died in the Towers, he had said, ‘You kissed someone you were not married to? If you were in my family I would cut your throat and wipe the floor with the blood, you disgusting bitch.’ He had spat on her and the Military Policeman had become uncontrollable and beaten him savagely.

‘According to Jeo you have committed to memory the satellite phone numbers of several al-Qaeda lieutenants,’ David says. ‘Give them to me.’

‘Did you beat him? He’s so gentle. He’d say anything to stop the pain.’

‘If a person would say anything to stop the pain, then he would probably start with the truth. No?’

Mikal closes his eyes and incurs the wrath of the Military Policeman who bellows at him to stay awake and pay attention.

‘Let me tell you something,’ David says. ‘The reason the United States isn’t torturing you, hooking you up to electricity or drilling holes in your bones, as some countries in the world do, is not that torture doesn’t work. Torture most definitely does work. But we don’t do it because we believe it is wrong and uncivilised.’

‘I want to see Jeo.’

Did Akbar say to him, while he was going in and out of sleep, that he must never give in to the temptation of grabbing the interrogator’s gun? ‘I think they wear it in the room because they want you to grab it and try to shoot them, so they can charge you with something.’ The soldiers wear them even when they are washing and dressing the prisoners, the prisoners’ hands and feet free of iron.

‘You are lying about Jeo. If you have him then go and ask him what my name is. Come back and tell me.’

‘So what he told us is a lie? Duly noted. We’ll have to make sure he knows what the consequences are for lying to us. Now tell me what your name is and where you are from.’

‘Ask Jeo.’

‘When we captured him he had thousands of Omani rials, American dollars and Pakistani rupees on him. Why do you think he had those?’

‘Ask him.’

‘Did you ever transfer money into Afghanistan from Pakistan — given to you by your al-Qaeda handlers in Pakistan?’

‘Ask Jeo.’

*

He dreams that his father and mother are travelling across land and sea, their path lit by a soul flame. They arrive and deliver him from his chains and lead him out of the cage. He dreams that he has turned into a boar and in mysterious happiness is rushing through the bright colours of various maps, an atlas, pursuing his female and when he finds her he becomes a man in a world so intense that the sound of a flower bud opening can kill and the bulbul is in the letters that spell the word bulbul. No longer bound to their flesh, the pair of them are among the ancient stars, enclosed in perfect crystals shaped like heroes and heroines and demons, true books and instruments of music. Outside his sleep, night has sealed all mirrors but in the clear glass of the dream both of them move fearlessly across the firmament towards knowledge not only of how the world began but of how it will end.

*

‘Did you try to count the teeth of a wolf?’ Akbar asks, pointing to the missing fingers.

‘Why are there pictures in the corridor?’ Mikal says. Their bright colours had pained his eyes. He passes them whenever he is taken to the medical tent where the dressings on his torso and hands are changed, to receive what he is told are antibiotic injections.

‘They are from children in America.’

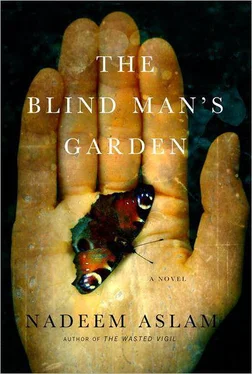

Drawings of butterflies, flowers, guns shooting at men with beards and helicopters dropping bombs on small figures in turbans.

‘They are letters to the soldiers from schoolchildren. The words say, Go Get the Bad Men and I Hope You Kill Them All and Come Home Safely . I saw one that said, We are praying for you, and said the Rosary for you today in class.’

‘I am going to escape,’ Mikal says to Akbar.

‘Don’t. They shot and killed someone who tried.’

He will have to locate and free Jeo within the factory and then they will break out. Or will he escape and come back for Jeo later?

‘How many guards are there?’ Mikal counts the MPs gathered near the cages. All captured Arabs are eventually sent to Guantánamo Bay. The others must be assessed to see if they should be. A shipment will leave today and since noon yesterday the MPs have been making preparations, laying out new jumpsuits, manacles, leg chains and spray-painted goggles on the floor in plain view of the cages. They pull on the leg chains, and lock and unlock the shiny chrome manacles, to make sure everything is in working order. No one can remain unaware of the rattling, and no one knows who will leave.

Now suddenly it is time, and the MPs are having great difficulty in getting some of the prisoners out of the cages. One prisoner clings to the wire of the cage and sobs as they prise him loose. Another falls to his knees, howling and shouting something in English. ‘He’s imploring for mercy,’ Akbar says. ‘“You promised you wouldn’t send me, Andrew. You promised, Steve, you promised.”’ Kissing the hands of the white men. Others though are just walking out, resigned to their fate, reciting the verses of the Koran.

An MP moves towards Mikal but continues past and enters the adjoining cage, which contains a Nigerian called Mansur. From him there had been complaints that everything in Afghanistan was inferior to Africa, even the rain and wind here were of an inferior quality. A Christian who had converted to Islam, and in the interrogating booth was constantly trying to convert the Americans, he is now being readied to be put on a plane.

Читать дальше