Mikal looks to the ground, then shakes his head. ‘I can’t.’

Sitting in a half-faint, the father opens his eyes for an instant and points to Mikal’s fingers. ‘Maybe when you touch the Prophet’s cloak, the pain in your wounds will stop.’

Mikal begins to walk away, still shaking his head.

‘How can you abandon fellow Muslims like this? Just help me carry him to the mosque. After that you can leave.’

Mikal stops and looks back.

‘I can’t carry him on my own, you can see that,’ the son says, on the verge of tears. ‘He’ll bleed to death.’

‘All right. You and I will take him to the mosque and then I will leave. And we are not stealing anything.’

*

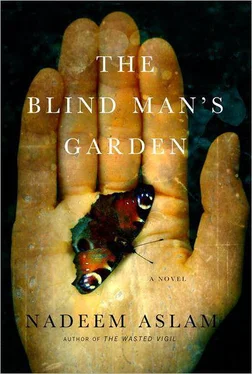

It’s past midnight when they see the mosque in the far distance, a glass moon shining above it. The sacred building stands on the expanse of blue and white snow, appearing separate and singular like something presented on the palm of the hand. The son was here on a reconnoitring trip last month but the area has been transformed by snow and ice. He whispers, ‘Glory be to Allah who changes His world and then changes it again but Himself changes not.’

The father has been babbling, hallucinating as he begins to die.

‘Run to the mosque and get help,’ the son tells Mikal when the man falls silent; then he lowers his father onto his back and, brushing the snow away from his chest, listens for a heartbeat. In his other hand he holds the torch they’d made with a branch and a torn turban. Although it has stopped snowing the snowflakes lie so thickly on them that almost half of their bodies are invisible.

Mikal shakes the whiteness off his face and clothing, patting himself into visibility, and sets off towards the mosque, at a slow pace — if he runs he grows faint. His mind retains very few impressions during the distance to its giant door. Now and then his two pieces of broken chain catch on something behind him, and thin plates of ice break under his feet when he encounters frozen puddles. He arrives at the mosque door but instead of knocking he convinces himself that there is no harm in lying down for a few minutes of rest. How long he lies there at the foot of the door he doesn’t know, but at one point when he tries to turn his head he discovers that his hair has become locked in ice, and later that the two sections of the ankle chain are also fused with the ground.

He lies looking up at the mosque that has the entire Koran inscribed on its exterior walls, domes and balconies. The calligraphy is said to be there on the interior walls and ceilings too. He watches the facade in the moonlight through half-open eyes and it is as though there has been a rain of ink — every drop that had landed on a surface had formed a word instead of a splash.

He looks at the sky as he sinks into sleep. Arabic is written up there in the cosmos too, he knows. Of the six thousand stars visible to the naked eye, 210 have Arabic names. Aldebaran, the follower. Algol, the ghoul. Arrakis, the dancer. Fomalhaut, the mouth of the fish. Altair, the bird … He falls asleep and there is a city under the stars in an undiscovered country, no lamp in any window. The only light is the constellations and the city’s minarets, each one of which is burning, a tall plume of fire, the flames streaming in the wind now and then. He enters the deserted city knowing that a group of black-clad figures is following him. Though he cannot see them he somehow knows that they have the natural fighting power of mountain lions, and he passes under several burning minarets before pushing open a door and entering a house and some time later he hears his pursuers come in. They spread out through the rooms and they make no attempt to lower their voices, to conceal their search for him. He climbs over the wall into the mosque next door. He picks up a book from a niche and removes a page and crumples it in his hand and then straightens it and places it on the floor. He does this with another page — introducing wrinkles into it and then putting it on the floor beside the first one — and then with another and then another, and eventually with all of them, lit by the light of the burning minaret, moving backwards as he leaves the paper on the floor. If anyone steps on them, he’ll hear it. When the floor around him is lined with the pages, he lies down at the centre of them and closes his eyes — a rectangular clearing, the exact dimensions of a grave.

*

There are moments of faint awareness through the dark. People moving near him. Hands that touch. Candlelight. Eventually he is able to awaken fully and things are called into being. He is on a sheet spread out on the bare floor, no pillow, and he is wearing a dry set of clothes. An aged man is tending to him with a gentle pensiveness, his beard falling to his stomach in two silver divisions.

‘Did you get them out of the snow?’

‘Who?’

‘I left two people outside.’ Mikal sits up slowly and looks around.

‘There’s no one out there.’

‘Maybe you can’t see them because it’s dark.’

‘It’s no longer night. It’s morning.’

The mosque is a ruin, and the man is burning a reed prayer mat and a heap of straw prayer caps to keep him warm. Propped up against the pillars are words that have fallen away from the walls, lines of calligraphy that curve and knot purposefully, collecting force and delight and aura as they go.

He stands up, wrapping the sheet around him as he rises. ‘In which room is the Prophet’s cloak kept?’

The man offers him a piece of bread. ‘The Prophet’s cloak is in Kandahar. What would it be doing here?’

‘I was told it was brought here.’

‘No. It’s always been in Kandahar.’ The man touches his forehead. ‘You are tired. Lie down and rest.’

‘I dreamt I tore pages out of a book of hymns to protect myself.’

The man thinks for a moment. ‘There is a kind of tree whose leaves do not fall,’ he says, ‘and in that it is like an ideal Muslim. But Allah understands if we don’t succeed in being perfect in this imperfect world.’ He smiles at Mikal.

Mikal begins to eat the bread, its core humid and porous. The man tells him that he is from Yemen, a foreigner trapped in Afghanistan. Scattered in various areas of the mosque, Mikal finds others like him, smelling more like wild animals than humans, entire families from Arab countries, destroyed-looking women and children. They have been on the run since October, making various journeys towards places of safety, to find some path back to their homelands. One little girl stands apart from other children, not participating in their activities, and he realises only after a while that she has no arms.

Though still very tired and weak, he opens the door to the south minaret and begins to climb up, looking out through the small recessed windows as he goes, the landscape altering with every turn of the spiral. Emerging into open air at the top, he examines his surroundings, the sky a water stain on paper. He is unable to understand why he was told the mosque contained the cloak, why he was sent on this trip.

Beside him on the facade, an ant is wandering in the shallow trough that forms the word ‘Allah’, carrying a wheat grain in its mouth, trying to climb out of the word but falling back into it again and again.

He turns around to leave and everything slides into place when he notices the large boot print in the snow next to his feet, a quick ray of recognition: the warlord sent him here to be picked up by the Americans. They were delivering him.

The Americans pay $5,000 for each suspected terrorist.

He rushes down the spiral — as fast as he is able, the two pieces of chain falling ahead of him and getting under his feet — and asks if they know the warlord who’d been holding him prisoner.

Читать дальше